To be an American, picking your way through the debris field of what used to be, at least nominally, a democracy—before Trump and his confederacy of dunces defiled, corrupted, plundered, pimped, sabotaged, and otherwise destabilized it from within—is to live in a nation permanently on edge, a nation whose nervous system has been short-circuited by post-traumatic stress, a nation that knows it will be retraumatized tomorrow and the day after tomorrow and maybe for every tomorrow to come by the farcical awfulness of just about everything.

Come to think of it, there’s no better word for what sociologists call our “lived experience” in post-Trump America than “farce.” Marx’s timeless aperçu (from The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, 1852) is more timely than ever: “Hegel remarks somewhere that all facts and personages of great importance in world history occur, as it were, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second as farce.” What Marx forgot to add was the third act, when farce becomes a permanent condition, an existential nightmare that never ends.

Trump’s four-year reign of terror and error was a gut-lurching mix of farce and nightmare, and it was that rollercoaster of absurdity and atrocity that made those endless four years so deranging, and gave them their mindwarping unreality.

That sense of finding ourselves trapped in a real-life theater of the absurd was compounded by his and his minions’ shameless denial of the irrefutable, nonstop gaslighting, and brazen fabrication, which kept us in a perpetual state of doublethink. It’s useful to revisit Orwell’s definition, in 1984, of his coinage:

To hold simultaneously two opinions which cancelled out, knowing them to be contradictory and believing in both of them, to use logic against logic, to repudiate morality while laying claim to it, to believe that democracy was impossible and that the Party was the guardian of democracy, to forget whatever it was necessary to forget, then to draw it back into memory again at the moment when it was needed, and then promptly to forget it again…

Still, for all the wounds Trump inflicted on the body politic, the slapstick depravity of his years in office seemed concentrated, if not contained, in the man himself. Part dunce, part Duce, a petulant Boss Baby and malignant narcissist with a Cheez Doodle-hued spray-on tan and that ludicrous combover, he embodied the Idi Amin Dada-ism of Trumpism. The image that captures him in all his Trumpiness is that viral video of him striving for a Mussolini-esque sneer of cold command as he mounts the stairs to Air Force One, oblivious to the fact that one shoe is gaily festooned with a hunk of toilet paper.

Of course, the damage he did and the horror he unleashed were no laughing matter. Moreover, as Chauncey Devega warns in a Salon essay, liberal schadenfreude won’t bring Trumpism to its knees. In fact, it may lull sane America into the complacent sense of superiority that is disaster’s precursor and fascism’s best friend. (Think of Hillary in the last days of her 2016 campaign, smugly amused by Trump’s “basket of deplorables” and confident that her coronation was inevitable.)

Still, if everyday life under Trump had an inescapable Death of Stalinabsurdism to it, those of us not cognitively impaired by a tinfoil helmet crowned with a MAGA cap could console ourselves with the knowledge that, somewhere beyond the reality distortion field of Trump and Trumpism, two and two did not equal five, and never would. Then, too, we took solace in the fact that the torture would end in four years, eight at most.

Now, we’re not so sure. The ability to tell a bald-faced lie without blinking; to stonewall and parse and prevaricate; to spin the press silly with staged media events and what the historian Garry Wills called Ronald Reagan’s “choreography of candor” have long been job qualifications for American politicians. But Trump took the assault on the very notions of empirical fact and non-partisan truth to epistemologically dizzying extremes, and his tactics are now the default mode on the Right, from the Orwellian doublespeak of GOP machers like Mitch McConnell to conservative disruptors like Ted Cruz to the weaponized irony of Fox News propagandists like Tucker Carlson to the conspiracy-addled jabber of Trumpist trolls cosplaying as politicians like Marjorie Taylor Greene.

That’s bad enough, but what really gives our moment its farcical horror is the unmistakable feeling that reality itself is trolling us. For the millions who feel politically impotent in a country where the filibuster, the electoral college, the deeply antidemocratic Senate, and a Supreme Court corrupted by rank ideologues have imposed minoritarian rule on the majority, the American experience, in 2022, is that of being trapped in a Black Mirror episode written by Edward Albee. Paradox and perversity are the dark matter of our collective reality, a reality whose mind-reeling absurdity makes laughter—the laughter of pitch-black despair—the only sane response, but whose moral horror strangles that laugh in our throats.

In his novel Watt, Samuel Beckett distinguishes between various types of “laughs that strictly speaking are not laughs, but modes of ululation”: “the bitter, the hollow, and the mirthless.”

The bitter laugh laughs at that which is not good, it is the ethical laugh. The hollow laugh laughs at that which is not true, it is the intellectual laugh. Not good! Not true! Well, well. But the mirthless laugh is the…laugh of laughs, the risus purus, the laugh laughing at the laugh, the beholding, the saluting of the highest joke, in a word the laugh that laughs—silence please—at that which is unhappy.

Unfortunately, we’re denied the catharsis of Beckett’s risus purus because, unlike his characters, we don’t have enough psychological distance on the American nightmare to appreciate its absurdity. We’re up to the gunnels in farcical horror.

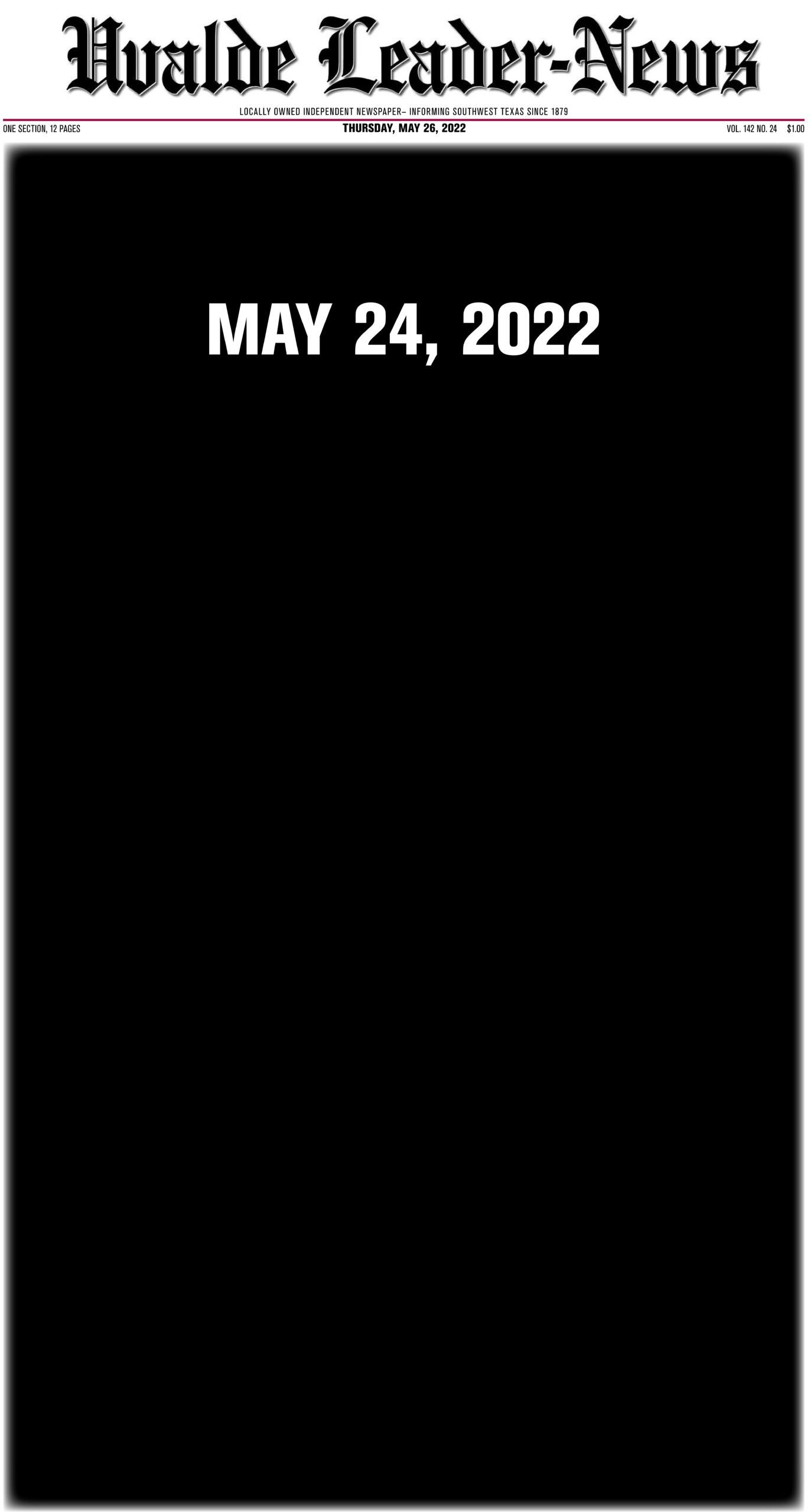

The massacre at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas is a case in point. The mindless slaughter of 19 children and two adults by yet another mass shooter is the horror; the nauseatingly farcical part is the Groundhog Day repetition of such carnage—268 such incidents, to date, in 2022 alone, depending on how one defines “mass shooting,” 17 of them since the bloodbath in Texas. Their mind-reeling frequency, and the cognitive dissonance induced by having to feel shocked/not shocked, sick with fury/benumbed by cynicism all at once, all over again, all the time, gives us that trapped-in-the-funhouse-hall-of-mirrors feeling. The rote “thoughts and prayers” from Republican pols puppeteered by Wayne LaPierre’s withered claw up their asses adds to the air of ghastly unreality. So does the headshaking about “partisan rancor” by “news analysts” whose scrupulous both-sides-ism requires them to feign amnesia about the GOP’s craven fealty to the NRA and its refusal, for years, to pass even the most commonsense gun-control legislation.

What makes us feel as if reality itself is trolling us is learning that heavily armed officers forbore to rush the gunman, for an hour,while the slaughter of the innocents proceeded apace inside the school because “they could’ve been shot.”

And that state troopers refused to act when distraught parents begged them to save their children but were all action when those same parents attempted to storm the school, pepper-spraying, tasing, handcuffing them.

The Eighteenth Brumaire—a date on the French Republican calendar—was Marx’s analysis of the French coup d’état of 1851. In the introduction, he declares his intention to “demonstrate how the class struggle in France created circumstances and relationships that made it possible for a grotesque mediocrity to play a hero’s part.”

Louis, Napoleon’s nephew, had ridden into the presidential palace on a wave of support from “the vile multitude,” as one sniffy conservative dismissed them. When his term was up, he refused to make a graceful exit as required by the constitution. He needed more time to Make France Great Again, he decided, so he staged a coup and declared himself emperor, confident that the masses—and the military—had his back.

In retrospect, Marx’s assessment of the “circumstances and relationships” that set the stage for Bonaparte’s coup looks uncannily prescient. Published in 1852, The Eighteenth Brumaire reads, with hindsight, as a checklist of the conditions necessary for fascism. In his role as sardonic sociologist, Marx wrings black comedy out of the nostalgia for a vanished golden age at the heart of every bourgeois revolution. In “epochs of revolutionary crisis,” he writes, bourgeois revolutionaries “anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes in order to present this new scene in world history in time-honored disguise and borrowed language.”

Sound familiar? A “grotesque mediocrity playing a hero’s part”? The reactionary dream of turning back the clock to a time when the nation was “great”? A would-be despot and his henchmen borrowing “battle slogans” from history’s playbook—like, say, “America First,” Trump’s nod to the isolationist America First committee, which in 1940 attracted nativists and Nazi sympathists, or the far-right insurrectionists’ use of 1776 as their rallying cry when they sacked the Capitol on January 6 in a tragicomic attempt to overturn the election and declare Trump king of America? As for the use of costumes “in order to present this new scene in world history in time-honored disguise,” you’re thinking, as I am, of the insurrectionists dressed as Uncle Sam, Lady Liberty, and Captain America.

From Trump’s bathetic descent down a golden escalator in Trump Tower (Live, from the blinged-out ‘80’s, it’s—The Donald!) to announce his run for the presidency to what he claimed was a crowd of “thousands” (in fact, a few dozen randos lured off the street by the promise of 50 bucks for waving prefab signs and helping “cheer him in support of his announcement”) to the horrifying denouement, four-and-a-half years later, of his Insane-Clown Presidency—the assault on the Capitol that the conservative commentator Ben Sixsmith quipped was “like the Storming of the Bastille as recreated by the cast of National Lampoon’s Animal House“—his regime had an air of unreality of about it. Everything Trump said and did seemed to be framed in air quotes, partly because it was, with very few exceptions, so stupefyingly imbecilic that no reasonably intelligent listener could believe his or her ears. For four interminable years, every American who hadn’t been cretinized by Trumpism found him- or herself thinking, more or less constantly, He can’t possibly be serious. He must be joking—conning you, me, the media, the gape-mouthed MAGA’s, everyone.

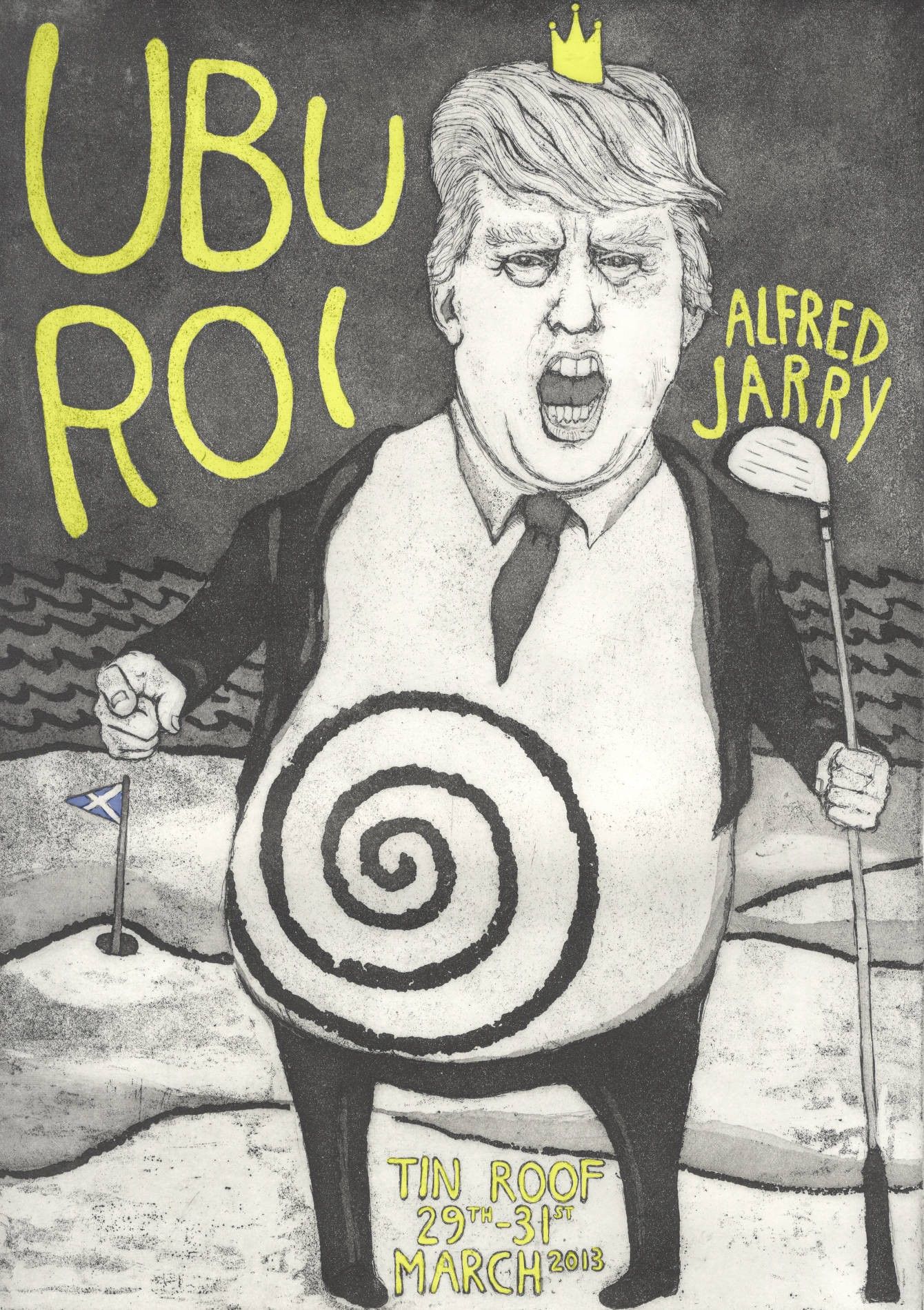

Like Alfred Jarry’s Dadaist dictator Ubu Roi, Trump wanted to de-brain everyone around him and, for good measure, drag them down to his moral level, the pit-toilet depths of corruption, mendacity, sociopathic nastiness, and a narcissism so malignant it makes Caligula look like the Dalai Lama. His America was equal parts theater of cruelty and theater of the absurd—in short, a farce, in which a grotesque mediocrity played a hero’s part. He’s gone, having strutted and fretted and tweeted his hour upon the stage, but the nightmare he dreamed seems not to be dissipating, and now we’re all part of it.

Mark Dery is a cultural critic, essayist, and the author of four books: Escape Velocity, a critique of the libertarian-bro ideology that dominated the Digital Revolution of the ‘90s; The Pyrotechnic Insanitarium: American Culture on the Brink, an unflinching look at American mythologies (and pathologies), from the Heaven's Gate cult to the Unabomber to the psycho killer clowns who haunt the collective unconscious; the essay collection I Must Not Think Bad Thoughts; and, most recently, the biography, Born To Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey. A wry observer of the American Scene in the tradition of H.L. Mencken, Gore Vidal, Mike Davis, and Joan Didion, Dery has written on subjects as disparate as the QAnon shaman, conspiracy theory, David Bowie as religious icon, Martin Heidegger as self-help guru, the masculinist agenda of Strunk & White, and Hannibal Lecter as high priest of (forgive the pun) good taste. He popularized the concept of “culture jamming” and, in his 1993 essay "Black to the Future," coined the term “Afrofuturism.” More at https://www.markdery.com Bylines: http://linktr.ee/markdery