International events sometimes highlight the connections between art and politics. Art and culture play a key role in defining and legitimating the narratives at such gatherings – and shaping the imaginary map of the contemporary world. For example, the Venice Art Biennale was launched in 1895 with the goal of restoring the city’s past cultural importance, in an attempt to “reinforce and support its cultural status, and to encourage tourism, in line with the growing European trend of creating international exhibitions” (Bruce Altshuler as cited in Ricci, 2010, 19–20). In the 59 shows since then, the Biennale has come to reflect the political transformations that have restructured Europe and the rest of the world. Its spatial organisation in the form of national pavilions enables us to analyse how representativeness produces a national meaning in keeping with each country’s political regime at particular points in time, and illustrates how international diplomatic relations can be examined through the prism of culture, and how national imaginaries are constructed 1. This debate extends to the interpretation of the Biennale as a space in which international relations between states are established and developed, and issues related to geopolitics or diplomacy are brought into play.

The relationship between art and politics

As art critic and curator Lawrence Alloway observed in one of the first studies of the exhibition based on the sociology of art, “in its history [the Venice Biennale] touches on unsettled problems of art in society” (Alloway 2012, 231). Thus the study of exhibitions involves examining nodes within systems, or within networks of transaction and value. Exhibitions function in multiple ways within broader contexts of artistic practice, markets and commercial relations, local and national economic development, and various kinds of political activities. Therefore political power can indeed be exerted at exhibitions; according to Alloway, studying the Venice Biennale constitutes “a confrontation with historical density” (quoted in Whitely 2012). Such a framework of analysis is particularly productive for surveying the narratives of art history that have recently begun to portray the exhibition format as a critical tool of rewriting history and studying the links among exhibitions, the production of knowledge and, consequently, power. Indeed, Michel Foucault proved that the spheres of knowledge and power are always linked (Foucault 1995).

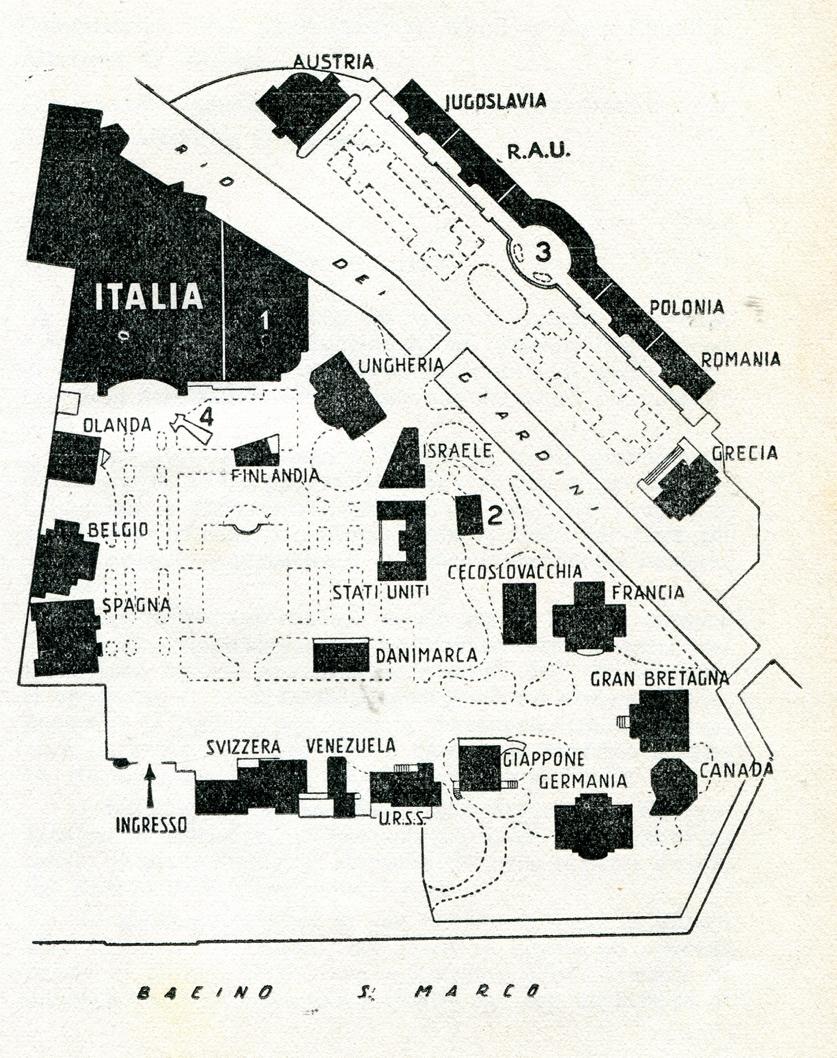

The unique configuration of the Venice Biennale in national pavilions allows us to explore in greater detail the connections among the exhibition format, the articulation of the imagined community of the nation state, and the development of a cultural policy based on diplomacy. The Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte della Città di Venezia is located in an enclave with strong symbolic connotations. Napoleon Bonaparte opened Venice’s public garden (Giardini di Castello) in 1807 after conquering the north of the country and proclaiming himself the king of Italy, arousing strong nationalist sentiments among Italians. The garden became a popular meeting point for the Venetian bourgeoisie and was chosen in 1887 as the venue for the National Art Exhibition, the immediate precedent of the Biennale. Twenty years had passed since the northeastern region of Veneto had been annexed to the Kingdom of Italy, and slightly less since the country was unified by the incorporation of Rome in 1870.

In the late nineteenth century, emerging debates on the idea of the nation crossed over from the political arena to the art world; the exhibitions’ ability to construct cultural identities made them patriotic instruments. Indeed, exhibitions and fairs enabled many Italian cities to exalt the nationalist sentiment produced by the birth of Italy as a nation state. Bearing in mind the precedent of the Venetian National Exhibition devoted exclusively to art – unlike the Industrial Exposition in Turin, or the Milan Triennale – the site founded by Napoleon was chosen to inaugurate the International Art Exhibition on 30 April 1895. Promoted by Venetian mayor Riccardo Selvatico, the Biennale became “one of the many locuses for debates about Italian nationhood and regionalism in the post-Unification period” (West 1995, 404). In his public announcement of the exhibition, the city’s mayor2 referred to its patriotic nature: “Venice has assumed this initiative with the double intention of asserting its faith in the moral energies of the Nation and of bringing the most noble activities of the modern spirit, without distinctions between countries, around a great concept of art” (Torrent 1997, 22). The show was thus created to celebrate Italian nationalism.

As educational and civilising agencies, national expositions and great universal fairs have played a decisive role in the formation of the modern state. Since the late nineteenth century their formulation and financing have been priority issues for nation states, which have become aware of their influence and importance in transmitting narratives. Hence, conceived as an educator and initiator of a new, modern culture for la giovane Italia [the young Italy], the Venice Biennale was set up as an exhibition of official, nineteenth-century academic art. In its early years it was displayed in the central pavilion of the Giardini di Castello; Italian and foreign artists were presented together and their works were arranged according to aesthetic parameters. Although the show began as an international exposition recommended by a committee of artists and intellectuals (who had insisted from the beginning on transcending its national character), the first biennials were chiefly national shows of works by artists in the Italian realist tradition3.

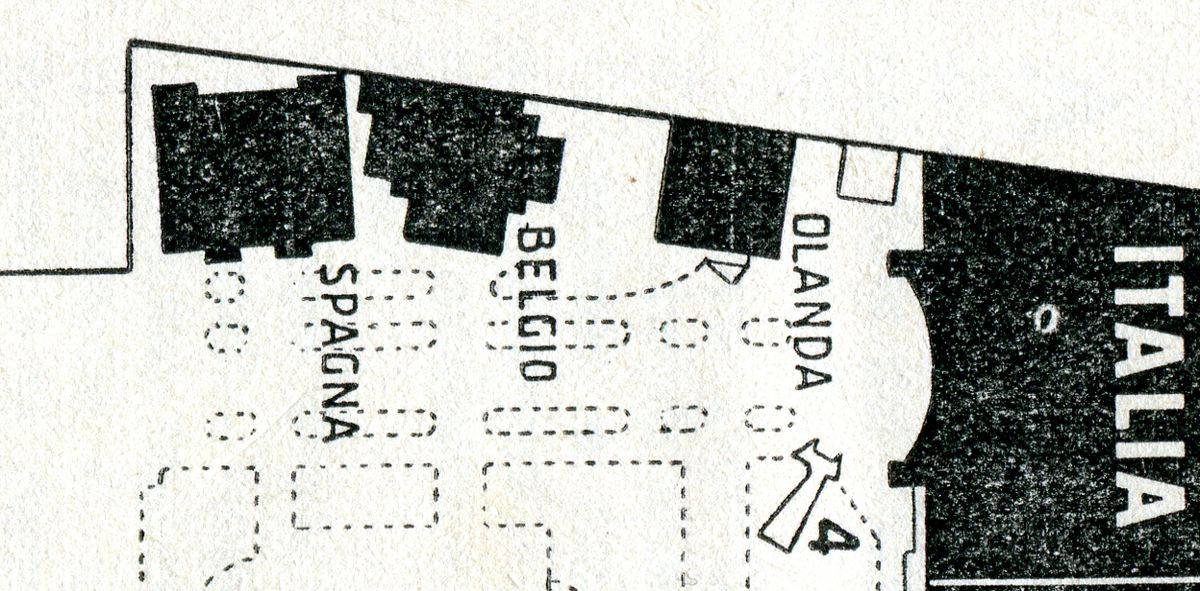

To make room for foreign artists, several countries were invited to build their own pavilions in the garden beginning in 1907. Each government’s display became a type of cultural embassy. In addition to addressing the lack of space, the decision heralded new relationships between the exhibition’s organisers and the participating countries.

When works of art are showcased in a space that has the ideological connotations of a national pavilion, they fulfil the function of diplomatic representativeness and help shape public perceptions of the identity and politics of nations. This symbolic function is an example of the advertising role played by art in international displays. The displays become ideological instruments that act as diplomatic channels for the political regimes they represent, and in turn reveal the relationship between art, politics and diplomacy on a global scale. In 1907, Belgium built the first national pavilion, followed in 1909 by Germany, Hungary and Great Britain, and in 1912 by France and Switzerland. Russia’s pavilion was inaugurated barely 3 months before the outbreak of WWI in 1914. The presence – and absence – of national pavilions on the Biennale premises reveals the cultural diplomacy behind the participation of the different countries as well as the Eurocentric nature of the exhibition. The Biennale was created to reflect this new European order of a national character that in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries organised the world into nations. The architecture of the pavilions and the content of the displays signalled each country’s relative geopolitical power. Thus examining the history of the Venice Biennale enables us to establish the global hegemony of the participating countries: the first countries to build their artistic embassies had either been (or still were) colonial powers, and the more or less significant presence of countries in the exhibition depended on the diplomatic relations between them. The artist Jonas Staal explains that the Biennale “can be considered a key battleground where the war for cultural hegemony is waged on all fronts” (Staal 2013). From the beginning, it served as a visual reminder of the close ties between international relations and national galleries.

While Belgium, Germany and the United Kingdom (great colonial powers at the exhibition’s founding) enjoyed prominent positions in the Giardini, countries that were burdened by a colonial past only began to install their pavilions in the mid-1950s. The exception was the US pavilion, erected in 1930, when the country was considered a hegemonic world power after WWI.

Biennale architecture and exhibitions as a symbol of political changes over time: the case of Spain

As Sharon Macdonald reminds us, exhibitions are products and agents of social and political change, “productive arenas in which to investigate questions of cultural production and knowledge more generally” (Macdonald 1995, 1). They are not neutral environments, but places where knowledge and power are continuously interwoven.

Biennale architecture has reflected political changes over time. Most notably, the national pavilions were altered whenever there was a change in power. For example, the Russian pavilion became the USSR pavilion in 1924 and flew the hammer and sickle flag. But perhaps the most obvious changes can be illuminated with a discussion of the Spanish pavilion, which was erected in 1922 – exactly a century ago. Spain’s presence in Venice has been one of the most constant in the history of the Biennale. It was first represented in 1895, the year of the official inauguration, before it had its own pavilion. During the first two decades Spanish artists regularly took part in the show held in the central exhibition area.

1930s: Spanish Civil War

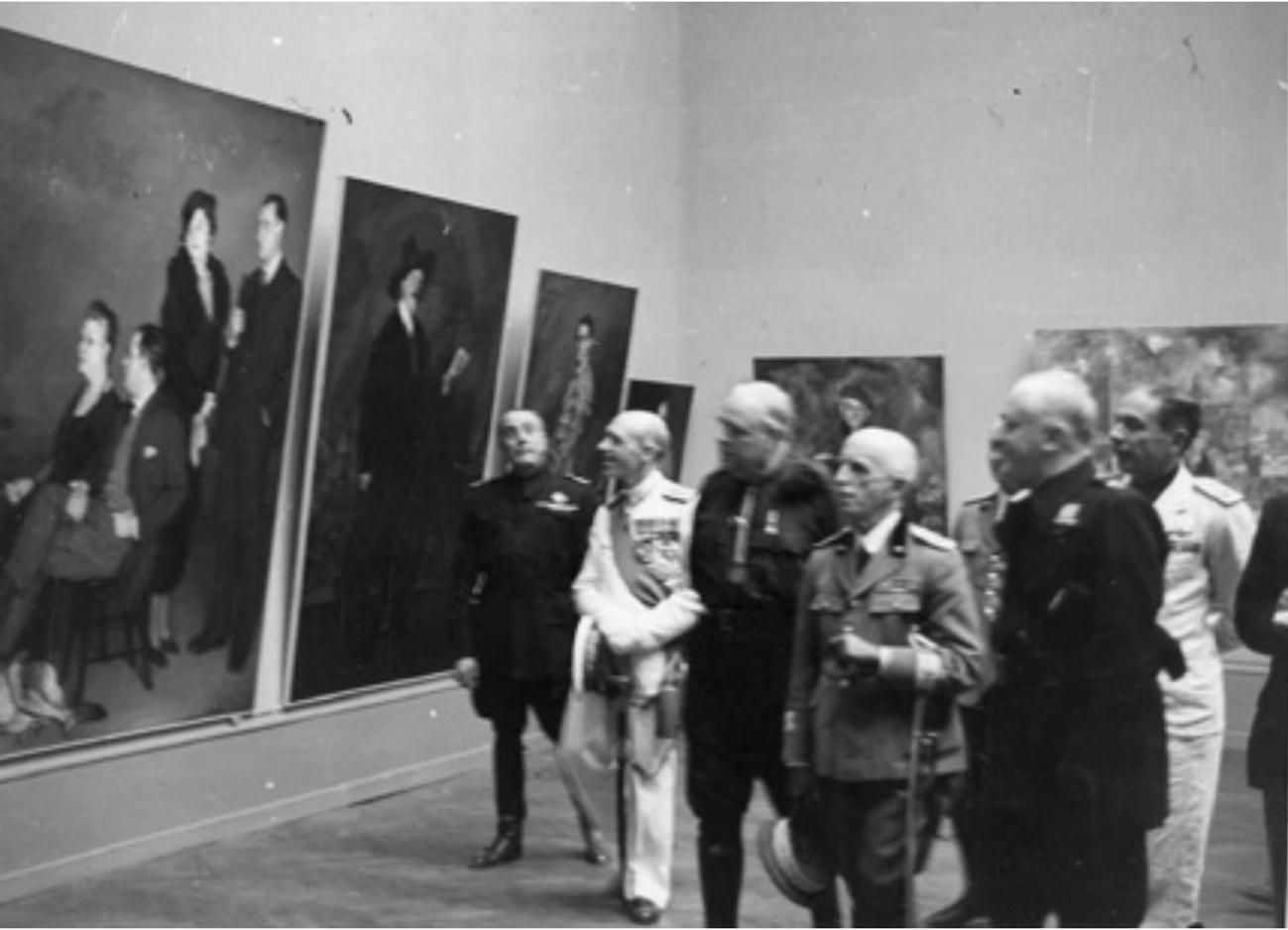

During the 1932, 1934 and 1936 exhibitions, the colours of the Republican flag adorned the building’s neo-Baroque façade, which was modified during the Spanish Civil War. In 1936, the Falangists, led by Franco, staged a coup against Spain’s Republican government that sparked the country’s civil war. In 1938, at the height of the Spanish War, Benito Mussolini commissioned the likeminded Falangists to curate the Spanish pavilion as an expression of support for their shared fascist ideology. The pavilion celebrated the Spanish nationalism that guided the ideology of those who had perpetrated the coup. In addition to Spanish artists, the Spanish pavilion of 1938 included Portuguese and Argentinean creators, offering the world an image of the geographic and cultural unity of countries with common interests to bolster the fascist ideal of empire.

The 1938 Biennale, a “war biennial”, was the most directly political of those in which the Franco regime took part, not only because of its ideological positions but also due to its use of art as propaganda. Venice was under the influence of Mussolini, Spain’s ally, and the Spanish pavilion flaunted its new discourse derived from censorship and interventionism in the sphere of culture and art it hoped to shape as a result of its attempts to erase the past. It touted nationalist values such as war themes, religious picture cards, portraits of Franco, etc. The shows significantly contributed to the development of Spanish national identity at a time when the regime’s objectives, like that of other European dictatorships, included defending the national order.

Orchestrating international exhibitions was a routine way for national governments to increase their visibility. The Spanish pavilion became one of the main showcases of the regime’s foreign policy, a tool used to strengthen national narratives and establish the image of the dictatorship on the international stage. It later came to symbolise Spain’s return to the international scene in the 1950s.

1940s: WWII and Spain’s international isolation

After Franco consolidated power, Spain entered a period of autarchy, with an economic policy based on the search for financial self-sufficiency and state intervention. Although Franco’s regime explicitly supported Nazism and Mussolini during WWII, Spain officially remained neutral. Anticipating an Allied victory, Franco launched a campaign for openness to improve the regime’s reputation and thus secure future international alliances. However, shortly after the creation of the United Nations (UN) in 1945, its General Assembly barred Spain from joining until it formed a new and acceptable government, and demanded that all UN members recall their ambassadors and ministers plenipotentiary accredited in Madrid.

The 1942 Venice Biennale was the last to be held until 1948, although Spain did not take part until 1950 due to its isolation following the defeat of Germany and Italy and the UN blockade. In the 1940s, Spain was represented by the ambassadors of the new order; art was used as propaganda.

The Allied victory motivated the Franco dictatorship to alter its foreign policy. As soon as the war was over, Franco removed the Falange from his government as its collaboration with the Axis powers had made it an awkward partner, instead naming an administration linked to the Catholic Church, which represented the anti-communist values of the United States. In the aftermath of WWII, cultural assimilation gave way to cultural exchange and cooperation. The political changes taking place around the world led to the abandonment of the policies of autarchy and the gradual openness of the regime.

1950s: Spain’s return to the international arena

In the 1950s Spain pursued a strategy of cultural diplomacy: culture was employed as a tool of public diplomacy designed not only to convince, but also to listen and understand external audiences with whom it could build long-lasting relationships. The regime launched a campaign to abandon the image that had prevailed during the early years of the dictatorship, giving way to a diplomatic strategy designed to improve Spain’s international reputation by projecting its neutrality in part through the arts. This phase was characterised by a new cultural approach to Europe and the United States, which played a vital role in Spain’s reintegration into the international community. Although the Truman administration in the US was reluctant to support the dictatorship, Eisenhower’s victory in the 1952 election paved the way for establishing relations with Franco, who was considered a moral ally for his anti-communist stance. The UN General Assembly’s reinstatement of Spain in 1950 marked the beginning of the end of its postwar isolationism. It was admitted to the Food and Agriculture Organization in 1950 and the United Nations Educational and Cultural Organization in 1952, and became a full member of the UN in 1955.

In the period leading up to Spain’s return to the Biennale in 1950, the role the arts should play in the regime’s new political strategy of openness and how public support of art should be organised were hotly debated. New foreign policies encouraged new forms of expression. The Cold War ideological battle played a key role in the evolution of the Franco regime, which was reflected in the Spanish pavilion in Venice. In 1952, architect Joaquín Vaquero Palacios designed a new and neutral façade to remove the fascist symbols from the Spanish pavilion. Works by artists like Antoni Tàpies or Joan Miró began to make a timid appearance at the 1952 and 1954 Biennales. Avant-garde art was not openly displayed until 1956, and finally took centre stage in the 1958 Biennale. Jorge Luis Marzo and Patricia Mayayo speak of a twofold treatment of culture by the dictatorship, “While it was brandished as an end in itself thank to the identification between national destiny and cultural destiny, it was also used as an instrument in the service of state interests, as a conveyor belt between the regime’s political and diplomatic objectives” (Marzo and Mayayo 2015, 158). This policy, which could be understood as an operation in cultural diplomacy, was chiefly implemented outside of Spain, given that the state’s support of the avant-garde focused above all on biennials, exhibitions in large museums and cultural events that accompanied Spanish diplomacy.

Cultural diplomacy, like the notions of public diplomacy or nation branding, entails actions designed to improve a country’s image abroad; these actions influence the construction of specific national identities, including through the articulation of cultural and artistic expressions. Milton Cummings most helpfully defines cultural diplomacy as “the exchange of ideas, information, art, and other aspects of culture among nations and their peoples in order to foster mutual understanding” (Cummings 2003). The political dimension of cultural actions can also be interpreted in the framework of what Joseph S. Nye described in the 1950s as “soft power” – the ability to obtain one’s desires through seduction rather than coercion or payment, in contrast to hard power, which is based on the economic and military forces that traditional diplomacy relies on (Nye 2003). In the context of art and museums, Christine Sylvester declared that “these popular institutions of civil society traffic in soft power” (Sylvester 2009, 172), and their objectives are achieved in the field of negotiation.

Some members of the organisation committee opposed the political and diplomatic meaning of the first display of Spanish art organised by the General Board of Cultural Relations of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for the 1950 Biennale. They criticised “the development of ways of painting and sculpting that may be valid abroad, though we recognise their falseness and their intention to destroy the foundations of our society” (Llorente 1995, 138). This critical report was drawn up by the curator of Spain’s 1950 participation in the Biennale, who refused to display some of the abstract works sent by the ministry. His vision, rooted in the assumptions that had until then dominated Francoism, diverged from the new cultural policy designed by the progressive strategy of openness.

The reply by the General Board of Cultural Relations to this letter revealed the intentions of the shapers of foreign cultural policy to adapt the contents of the Spanish pavilion at the Biennale to the other countries’ displays. This marked the beginning of the new artistic foreign policy, which since the Hispano-American Biennale of 19514 had included works by young representatives of the Spanish art informel movement, such as Josep Guinovart and Tàpies, as an example of the first official support of abstraction. So, the Hispano-American Biennale “introduced the complete normalisation of the art scene, proving the impossibility of an official Falangist art and paving the way for the avant-garde that was, however, profoundly corroded by hypocrisy, revision and a terribly conservative concept of culture” (Marzo 2010, 44). For Spain, the commitment to abstraction implied an anti-communist stance and supporting Western liberal democracies. This debate between Socialist Realism in the East and Abstract Expressionism in the West continued throughout the Cold War, politicising the styles that represented both blocs. Abstract art, with its different expressions in each country, was a common language, apparently (and paradoxically) devoid of social and political connotations.

At the next Biennale held in 1952, the Spanish pavilion displayed the work of young artists like Tàpies and Guinovart, anticipating the triumph of art informel as an example of modernism as well as Spanishness. Yet the need for artistic renewal, illustrating the regime’s strategy of openness, aroused reservations in Spain’s most conservative sectors. Although the avant-garde artists exported by the dictatorship offered an image of openness, they were in fact artists removed from republicanism and exile, whose works had no political overtones and did not challenge the regime’s values. As described by historian Alicia Fuentes Vega, who has studied the theme of Spanishness in the art of the Franco years in depth, the regime’s new strategists “had to concoct a credible and, above all, an acceptable discourse of modernism for the regime’s internal conservative media” (Fuentes Vega 2011, 187).

Abstraction thereby became the correct language for opposing the realist aesthetics of communism, and for representing the new Francoist aesthetic. A campaign was launched to provide the avant-garde with a patina of Spanishness in response to international demands in the aesthetic field without betraying national values and, above all, to rebuild the dictatorship’s damaged reputation. The idea was to suggest that the abstraction practiced by Spanish painters formed a coherent part of the Spanish art tradition. The Francoist regime initiated a debate to reflect on the true role of art in an effort to situate Spain’s characteristic traits within Western cultural production, immersed in a process of globalisation in the 1950s. Spanishness was a key theme for understanding the development of the avant-garde, and this twofold instrumental task represented both national identity and the expressions of vitality of the regime, which desperately needed to project an image of liberalism in the emerging diplomatic and economic order.

The art informel movement synthesised this modernity with the absence of political ideology or criticism. Developed chiefly between 1957 and 1960 just as the El Paso group was emerging, it enabled Spain to join the international avant-garde art circuit. Its use of realistic materials and a severe, austere and intense Spanish palette evoked the best Spanish pictorial tradition of Velázquez, Zurbarán and Goya. Official criticism worked to ensure that art informel was recognised as a modern Spanish style, while the regime drew analogies with contemporary art movements around the world in countries like France and especially the United States, with which Franco had already opened up channels of dialogue. Exhibitions by American Abstract Expressionists could be seen in Spain as a part of the US diplomatic plan to introduce Action Painting in European capitals. In the early years of the Cold War, American cultural policy strove to counter the effects of the aesthetic discourse of the left wing. Hence the Spanish avant-garde was legitimised by its projection in Abstract Expressionism, and modern art was thus divested of social reality. Cultural exchanges proved essential to Spain’s international recognition in the 1950s; in short, the Spanish state invented the avant-garde in its search for a style that could rival the trends that were developing in Europe and the USA.

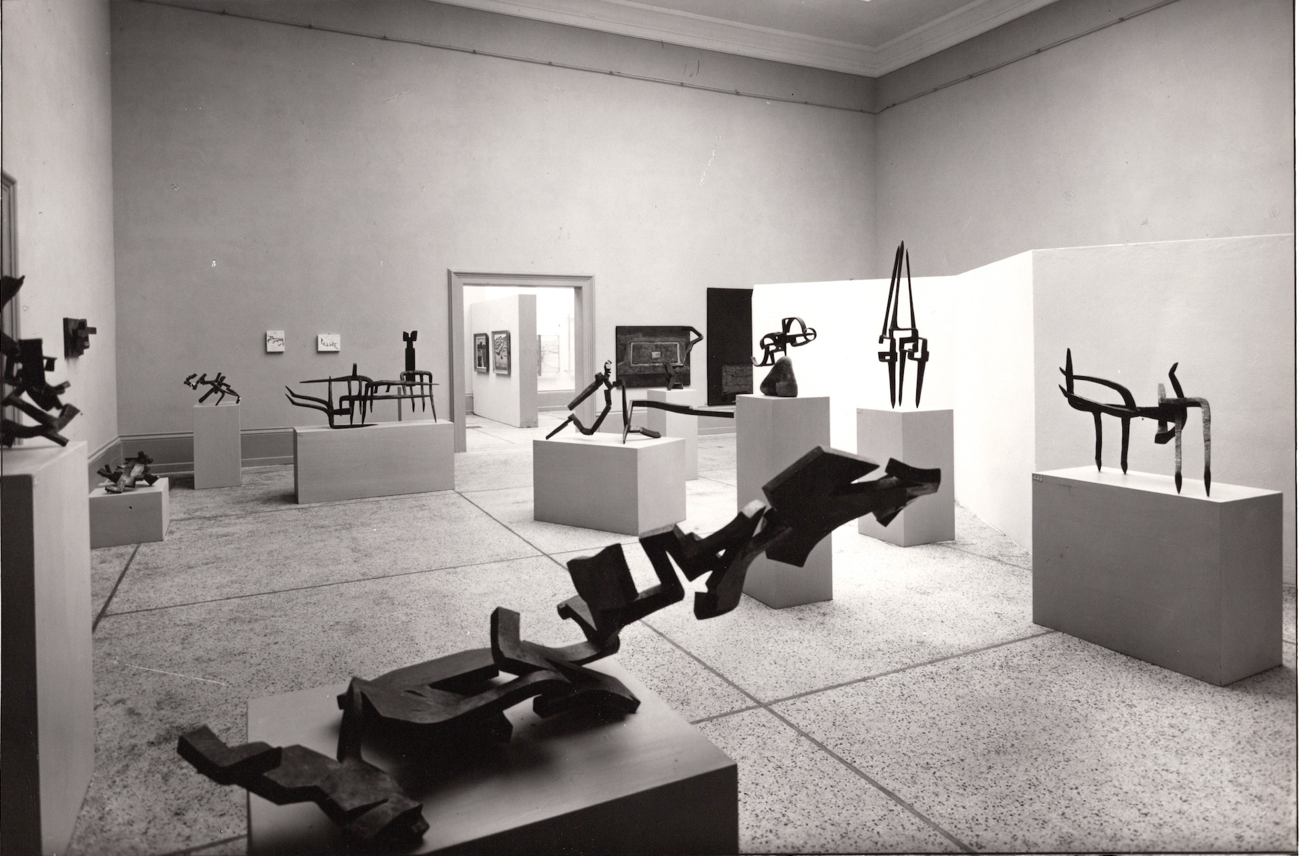

The balance between tradition and modernity that prevailed from 1950 to 1956 was upturned in 1958 by a series of political and cultural events that occurred in Spain. The appointment of a new technocratic government in 1957 had resulted in new economic development policies known as desarrollismo, in keeping with the new agreements signed with the United States. The country’s foreign exhibition programme was fully committed to the “new” art. As a result, the 1958 Biennale showcased new Spanish artists and served as the backdrop of their success – making abstraction a key tool of cultural diplomacy in Western Europe. International art critics recognised the Spanish Pavilion displaying art informel as the best in the show. Sculptor Eduardo Chillida won the Grand Prix for Sculpture and Antoni Tàpies was awarded the Second Prize for Painting. The artists who represented Spain that year celebrated the success of the regime’s cultural diplomacy campaign to promote parallels between Spanish art and international trends. But although changes had taken place in Spain, it was still ruled by a dictatorship, and the end of its international isolation was due largely to overarching Cold War trends.

A favourable context for experimenting with power relations

This article illustrates how the successive Spanish exhibitions held at the Venice Biennale during the Franco dictatorship became devices of ideological transmission, shaped to meet the specific political strategies of each period. Tensions and power struggles came to light at key moments, such as when the Spanish pavilion was transferred to the instigators of the military coup in 1938, during the Spanish Civil War, or when it accommodated the abstract trends that Venice favoured to emphasise the country’s cultural proximity to the Western powers. The Franco regime designed and pursued an ambitious strategy of cultural diplomacy at the Biennale that helped it attain its political objectives. Spain was accepted into the European and American diplomatic context thanks to the promotion of a modern image of openness that included adopting art informel as a tool of integration into the international art scene. In addition to being a modern style, art informel represented identity and nationalist values, legitimating the Francoist discourse of national identity. National cultures, according to Fiona McLean, “construct identities by producing meanings about the nation with which we can identify, meanings which are contained in the stories which are told about it, memories which connect its present with its past, and images which are constructed of it” (McLean 1998, 244). This description recalls the strategy of conflating Spanishness with art informel. Accordingly, the Spanish pavilion at the Venice Biennale was a space of national representation for shaping – through Spanish abstraction and art informel – a modern image of the dictatorship in the international unconscious.

Governments have always used the arts to further their political and economic objectives. While it has always been a crucial factor in foreign policy, after WWII, culture was recognised as a value in itself, subject to neither political nor economic determinants. Culture gradually came to be understood as the third pillar of foreign policy, or, to paraphrase Coombs, the fourth dimension of foreign policy after the economy, politics and defence (Coombs 1964, 1-2). The arts therefore become a key element in the stability of a power system, and through the cultural policy implemented in each of the national pavilions, the structure of the Venice Biennale reflected how the various countries exerted their hegemony over culture by attending it (or not). The world, as we learn from Nye, is not only driven by military force or hard power, but by cultural diplomacy, artistic and ideological means – i.e., soft power, or “the ability to entice and attract” (Nye 2008, 95). In addition to political values and foreign policy, Nye has examined the use of the arts to shape public opinion around the world. If the Venice Biennale is an ideological space, “a power space like any other institution,” to use Sylvester’s definition of art museums (Sylvester 2009, 184), then Spain’s representation at this event over the last 100 years is a good way to address the relationship between art and politics over the course of its history.

NOTES

1 We compare the mechanisms used to construct national communities with those that governments use to build what Benedict Anderson terms ‘imagined communities’ in spaces of representation such as the Biennale (Anderson 2006, 6). Anderson defines the nation as “an imagined political community,” and clarifies: “It is imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion.”

2 The event was linked to a sense of national pride. The backdrop to the origins of the Biennale was also formed by the celebration of the 25th wedding anniversary of Umberto I and Margherita of Savoy in 1893, an excuse that Mayor Selvatico used to propose the idea of an international art exhibition held regularly to commemorate the occasion.

3 The Biennale did not truly become international until the end of World War II (WWII), after being influenced by fascist extremism while Mussolini was in power.

4 The 1st Hispano-American Biennale held in 1951 was the first great experience in the production of large-scale exhibitions and the first great platform for the regime’s cultural propaganda, both within and outside the country. To give Spanish culture a foothold abroad to mobilise support and alliances after its wartime isolation, the ICH was set up in 1945 as a cultural diplomacy school that would promote – through culture – cooperation and negotiation between states as a means of attaining political objectives. As such, it was an observatory of power to monitor those forms of cultural behaviour that could be used to enhance the image of Francoism.

Despite the mistrust and opposition of the sectors supporting the academicism that had prevailed during the first decade of Francoism, in the late 1940s the driving forces behind the modernisation of the regime justified an aesthetic turn. The ICH generation sought a cultural and artistic model that could represent the openness of the regime without questioning the dictatorship, and facilitate Spain’s international recognition. This model became the exportation of abstract art – specifically, of Spanish art informel. The sectors linked to the ICH longed to transform artistic academicism into a powerful avant-garde current that would place them on an equal standing when they travelled abroad. Exporting the avant-garde was therefore an operation designed by the regime to expand its influence abroad.

Agar Ledo Arias is a curator and art historian based at the Museo de Pontevedra, Galicia (ES). She previously worked as a researcher and advisor at the Museo Reina Sofía Collections Department (2019–2022), where she integrated the curatorial team of ‘Communicating Vessels. Collection 1881-2021’, the global reorganisation of Museo Reina Sofía’s entire collection. Agar Ledo Arias is interested in the political and social implications of art. Her career also features exhibition spaces such as MARCO Vigo (2006–2018), the Centro Galego de Arte Contemporánea (1998–2004) and the Fundación Luis Seoane (2005). In addition to earning an MA in Art & Politics (Goldsmiths, University of London) and an MA in Museology (Universidad de Alcalá), she has enjoyed training residencies at Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, Norman, OK (USA), Le Consortium, Dijon (France), Musée d’art contemporain de Lyon (France) and ICI-Independent Curators International, New York (USA).

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alloway, Lawrence. The Venice Biennale 1895-1968: From Salon to Goldfish Bowl. New York: New York Graphic Society, 1968.

Altshuler, Bruce. “Exhibition History and the Biennale”. In Starting from Venice: Studies on the Biennale, edited by Clarissa Ricci. Milan: Et. al, 2010.

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso, 2006.

Aron, Raymond. Peace and War: A Theory of International Relations. New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, 2003.

Barreiro, Paula. “La invención de la vanguardia en la España franquista: estrategias políticas y realidades aparentes”. In ¿Verdades cansadas? Imágenes y estereotipos acerca del mundo hispánico. Madrid: CSIC, 2009: 347-362.

Bennett, Tony. “The Exhibitionary Complex”. In The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. London: Routledge, 1995.

Cockcroft, Eva. “Abstract Expressionism, Weapon of the Cold War”. In Artforum vol. 12, no. 10 (June 1974): 39-41.

Coombs, Philip H. The Fourth Dimension of Foreign Policy: Educational and Cultural Affairs. New York: Harper & Row, 1964.

Cummings, Milton. Cultural Diplomacy and the United States Government: A Survey. Washington, D.C.: Center for Arts and Culture, 2003.

Di Martino, Enzo. La Biennale di Venezia: 1895-1995. Cento Anni Di Arte E Cultura. Milan: Giorgio Mondadori, 1995.

Filipovic, Elena; van Hal, Marieke and Øvstebø, Solveig (eds.). The Biennial Reader: An Anthology on Large-Scale Perennial Exhibitions of Contemporary Art. Bergen: Kunsthall and Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2010.

Foucault, Michel. The Archaeology of Knowledge. New York: Pantheon Books, 1972.

——————— Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books, 1995.

Fuentes Vega, Alicia. “Franquismo y exportación cultural. El papel de ‘lo español’ en el apadrinamiento de la vanguardia”, Anales de Historia del Arte, No. (extra), 1, (2011): 183-196.

Guilbaut, Serge. How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art. Illinois: The University of Chicago Press, 1983.

Jiménez-Blanco, María Dolores (ed.). Campo cerrado: Art and Power in the Spanish Postwar, 1939 to 1953. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2016.

Jones, Caroline A., The Global Work of Art: World’s Fairs, Biennials, and the Aesthetics of Experience. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Llorente, Ángel. Arte e ideología en el franquismo. 1936-1951. Madrid: Antonio Machado, 1995.

Macdonald, Sharon. The Politics of Display: Museums, Science, Culture. London and New York: Routledge, 1995.

Martini, Maria Vittoria. “The Space of the Exhibition: The Multi-Cellular Structure of the Venice Biennale”. In Pavilions. Art in Architecture. Brussels: Muette, 2012.

Marzo, Jorge Luis. ¿Puedo hablarle con libertad, Excelencia?. Murcia: Centro de Documentación y Estudios Avanzados de Arte Contemporáneo (CENDEAC), 2010.

——————— and Patricia Mayayo. Arte en España (1939-2015). Ideas, prácticas, políticas. Madrid: Cátedra, 2015.

McLean, Fiona. “Museums and the Construction of National Identity: A Review”, International Journal of Heritage Studies, vol. 3, no. 4 (1998): 244-252.

Mulazzani, Marco. Guida ai padiglioni della Biennale di Venezia dal 1887. Milan: Electa, 2014.

Nye, Joseph S. “Propaganda Isn’t the Way: Soft Power”. The International Herald Tribune (January 10, 2003).

——————— Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. New York: Public Affairs, 2004.

——————— “Public Diplomacy and Soft Power”. In Public Diplomacy in a Changing World, edited by Jeffrey Cowan and Nicholas J. Cull. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science series, vol. 616 (March 2008): 94-109.

Quaggio, Giulia. “El poder suave de las artes. La Bienal de Venecia y la diplomacia cultural entre Italia y España (1948-1958)”. In Historia del presente, no. 21, 2013: 29-48.

Sheikh, Simon. “None of the Above: From Hybridity to Hyphenation. The Artist as Model Subject, and the Biennial Model as Apparatus of Subjectivity”. In Manifesta Journal, no. 17, April 2014.

Staal, Jonas. The Venice Biennial. Ideological Guide, 2013.

http://venicebiennale2013.ideologicalguide.com/about/

————— “Art. Democratism. Propaganda”, e-flux no. 52 (February 2014).

Sylvester, Christine. Art/Museums: International Relations where We Least Expect it. Colorado: Paradigm Publishers, 2009.

Torrent, Rosalía. España en la Bienal de Venecia. 1895-1997. Castellón: Diputació de Castelló, 1997.

Tusell, Genoveva. “La proyección exterior del arte abstracto español en tiempos del grupo El Paso”. In En el tiempo de El Paso. Madrid: Centro Cultural de la Villa, 2002: 87-117.

West, Shearer. “National Desires and Regional Realities in the Venice Biennale, 1895-1914”, Art History vol. 18, no. 3 (September 1995): 404-434.