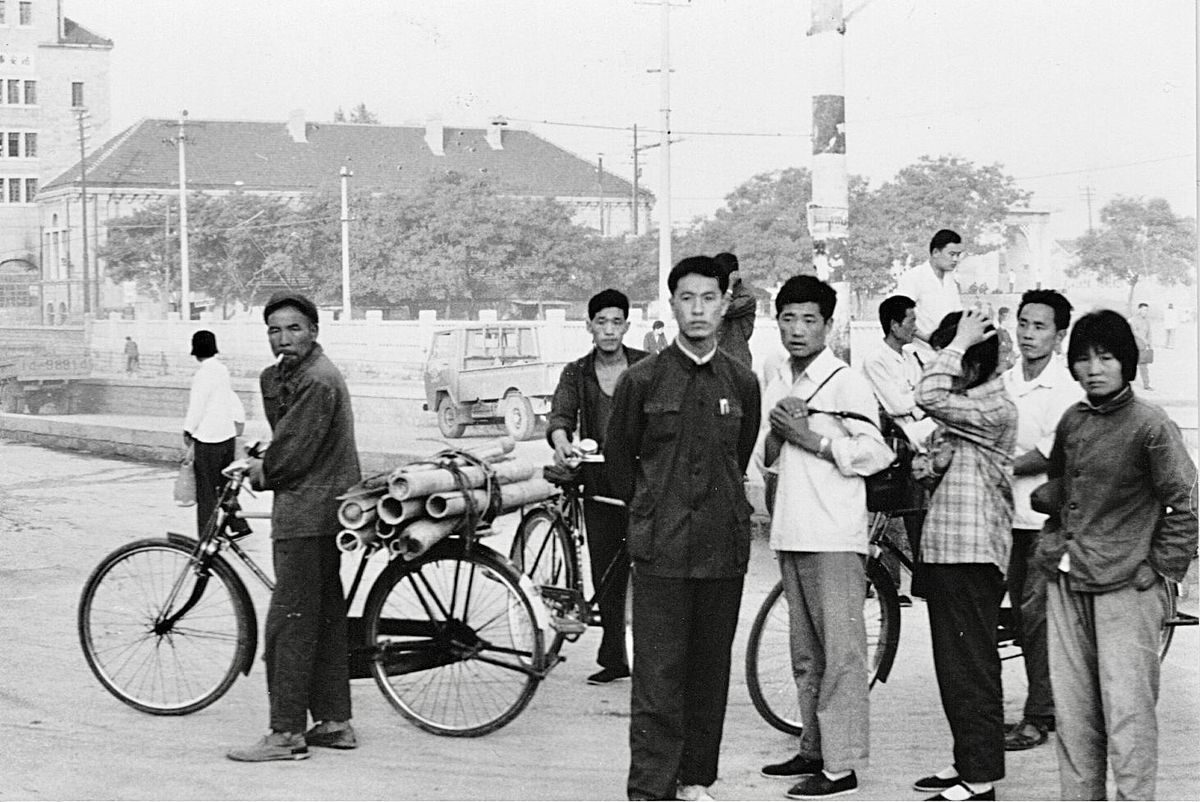

Who are the Chinese and what is China? These are seemingly irreverent and vacuous questions. Surely, the answers are evident to any Cartesian-minded person. And yet these are questions I have increasingly felt the need to address over the past three decades, from the moment I started questioning my own position, posing the questions about the source of my legitimacy to inquire into and narrate China and "the Chinese", which in turn demanded that I ask what, when and who constituted China and the Chinese.[1]

For the purposes of this brief essay, let China be the reality that is the People's Republic of China today – plus "the Chinese-speaking world", a world beyond the confines of mainland China both geographically and historically, a world fragmented, complex and diasporic. And let "the Chinese" be not only the people who populate these imagined and real spaces, but also those who, for the white person, "look Chinese". In evoking the latter, I am thinking of hybrid communities; communities that I call Chinese British, but also those who prefer to refer to themselves as British East Asian or British East and South-East Asian. I have already outlined my misgivings about naming these communities in this way elsewhere in Postcolonial Politics, so I will not go over them again here.[2] In any case, we can only respect the wishes of those who thus construct themselves. As Étienne Balibar has reminded us "all communities are imaginary; but imaginary communities alone are real."[3]

There are three main issues I address here, although not necessarily in a proportional or mechanical fashion. First, the legacy of Orientalism, Sinology and China-watching, in which China is seen as an object and a space in which "the Chinese" are largely absent and in any case have no agency. Second, the enduring dominance in the West of white observers, scholars and curators in the narration and display of China and Chineseness, and the relative absence of Chinese actors. And, third, the preference for, and the prioritisation of, the "authentic" Chinese over the local, the hybrid and the diasporic. These different manifestations of control over the narrative, over the "big picture", have been omnipresent not only in written text, but also on screen and stage, and in galleries and museums – wherever China and the Chinese are to be told or shown. Beyond the library, in the world of art and archaeology – a heady mélange of scholarship, connoisseurship, ostentatious display, and let us not forget, money – problematic issues of narration and exhibition are exacerbated, thrown to the fore. There are here much larger questions of colonialism and how to decolonize existing colonialist structures and mentalities, and these also will be addressed. But, my immediate concern is with that preference for the "authentic" over the local; with what happens when the steely world of high art and culture is confronted by the messy business of local, hybrid, post-colonial communities.

I have spent much time over the past thirty years in attempts to acquire for "Chinatown" communities dedicated spaces in which to display and foreground their particular histories and issues. But local governments and the so-called "business communities" they choose as partners have always been more interested in the "real deal", in the China over the seas, in the illusory prospect of attracting Chinese money and China trade. Naturally, Chinatown museums and local creators are on the wrong side of the equation since they demand financial support. Yet, it remains that the local is the "real deal". The local in the UK context belongs to that blighted, ever-present, post-colonial "legacy" deriving from Britain's nineteenth-century imperialist adventures in what is now China and south-east Asia.

The establishment's preference for the imported "authentic" over the local is nothing new. The efforts of local Chinese communities to foster writing in the early 1990s, such as Jessie Lim's Lambeth project, were overshadowed by the appearance of English translations of post-Tiananmen Chinese exiled poets and novelists. Only recently has a new generation of Chinese British writers begun to make their mark.[4]

So several problems may be crudely identified. First, the dominant whiteness of gatekeepers, and second, the privileging of the "authentic" over the less spectacular local, post-colonial, community of creators and their needs. Then there is also the issue of the local, post-colonial subject's sense of subjecthood, upon which the establishment's constant promotion of the "authentic", intertwined with the dominant white community's, collective imaginary of "Chineseness" may have an insidious effect: the generation of a sense of inferiority. Is the local, post-colonial subject quite Chinese enough, are they sufficiently "authentic" compared to first-generation Chinese practitioners? While nostalgia and a desire to seek out "roots" may lead second generation, local creators to "explore" their Chineseness, should a dominantly white fairy story of Chineseness be their guide?

There are two monolithic impediments to diasporic expression of Chineseness: dominantly white scholarship, and the myth and seemingly unassailable authority of the "authentic".

Who has a say over how to frame China and Chineseness? Who is authorised to talk about things Chinese? Who can speak for the diaspora? Who is legitimate in doing so? Let me say immediately that I am not suggesting some sort of "colour bar" that would preclude white people from discussing China and "the Chinese". People do not display in their physiognomy either their origins, or their personal trajectories, or their investment in the decolonization of knowledge. And, simply because someone "looks Chinese", and this should be obvious, does not signify they will be free of a dominant white perspective. Indeed, a central plank of the project of colonialism was and is, what Bourdieu, alluding to Max Weber, described as, "domesticating the dominated."[5]

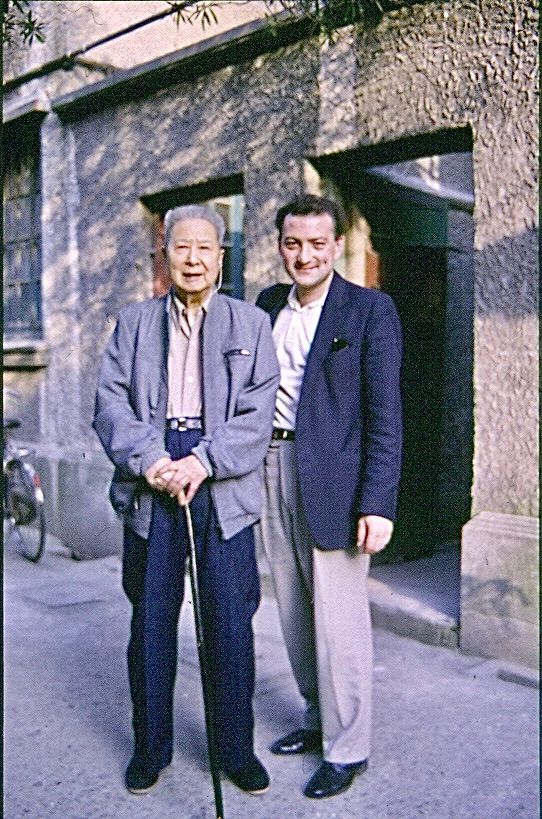

However, white academics, curators and "experts" need to address a hard reality: that we make our living and build our careers out of framing and representing the Chinese Other, and therefore we are obliged to interrogate how and by what authority we do so. Posing the questions of legitimacy and positionality is the first step to recognizing the problem of frequently "innocent", unreflective white scholarship. This too is part of the legacy of colonialism. As Stuart Hall remarked, the condition of postcoloniality affects us all regardless of colour, and "in this postcolonial moment, the sensibilities of colonialism are still potent. We all of us – are still its inheritors, still living in its terrifying aftermath."[6]

White Saviour Complex

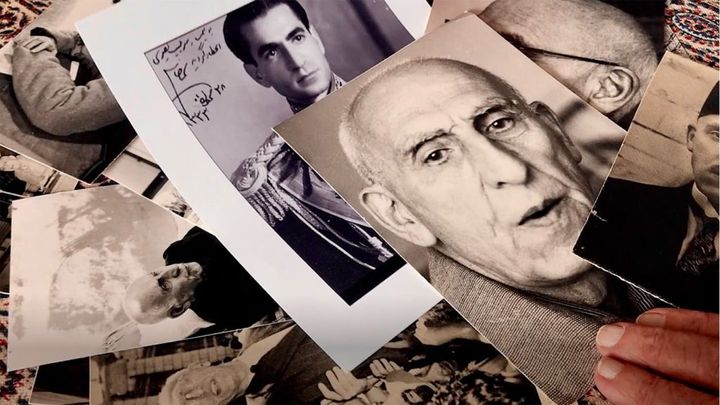

Those of us in the field of modern Chinese literary and cultural studies for many years laboured against a background of disdain for the contemporary Chinese reality, and an almost obsessive reverence for the past – albeit a past framed and constructed in Europe and America and Japan. Such was to be expected, classic Sinology was a strand of Orientalism. And yet, those of us working on Chinese culture in the twentieth century, just like the dyed-in-the-wool Sinologists, worked under the shadow of destruction. Whereas those invested in "ancient China" were concerned for their oracle bones and artistic artefacts, we the "modernists" harboured similar concerns for the preservation of our objects of study. We also had inherited the trait of arrogance from the tradition of Orientalism, and we suffered too from white saviour complex, believing somehow that we were custodians of Chinese texts and culture, protecting them from barbarism, upholding writerly freedoms and crusading against censorship. This was especially so during and after the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution which saw much destruction of objects and texts, and much violence directed against intellectuals. White saviourism was thus an easy mentality to slip into and a difficult one to shed.

For a period of about thirty years, until the advent of Xi Jinping, there was a halcyon period of greater academic and cultural freedom in China, although it remained relative. But, for a decade now the screws have been tightened on academics, especially in the humanities, law and social sciences. Today, given the ever more totalitarian nature of the Chinese regime, academics working "on" China are faced with a particular problem. There is a need to contradict the Chinese party-state's official narrative. Scholars emanating from the PRC – even those installed in universities outside of China – are often wary of frontally critiquing the regime and its policies. It is an aversion, especially among young scholars that manifests itself in their steering clear of sensitive subjects, or avoiding the present moment altogether. It is understandable; the means of coercion and retribution available to the party-state are sinister and ubiquitous. So, of course, there is a need for academics and other intellectuals who have nothing to fear, except perhaps being denied a visa, to speak out. However, it is easy to fall back into an outmoded colonialist positionality of the "civilised" proposing and maintaining a standard perceived as unattainable by the "uncivilised".

Again, what matters is not whether one is white, but how one positions oneself. What is in question is the ruthlessness of a regime, not its "race", not the colour of its "population". What is paramount is to avoid both the old Orientalist disdain for contemporary Chinese subjects and the adoption of a white saviour posture, where the liberal white scholar stands in for "the Chinese" in the recounting and interpreting of Chinese contemporary realities.

To say this is not to condemn wholesale an entire field of China specialists. However, and I say this not merely having observed and experienced China-watchers and specialists over the past four or five decades, but having reflected on my own trajectory: A white scholar cannot "work on" China innocently.

Institutional Racism and the French Connection

Anyone in the field of Postcolonial studies acknowledges the debt we owe to the theoretical work by Francophone Afro-Caribbean writers and cultural theorists who theorised postcolonialism while living under what was still, and is still, French territorial and ideological colonialism. Such writers as Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, Édouard Glissant, Ina Césaire, Gerty Dambury and Françoise Vergès, to name just a handful. In both the French metropolis and in the still extant Caribbean colonies, governed as French departments, the refusal to face up to institutional racism and the need for a decolonializing reading of France's history is nearly total. "Colonialism persists," wrote Stuart Hall, "despite the cluster of illusionary appearances to the contrary."[7] Nowhere is this more strikingly the case than in France and its former empire, where the mirage of French universalism obfuscates and denies demands to confront ongoing colonialist injustice.

Whereas in the UK a thin, albeit fast-fading, veneer of multicultural diversity masks the reality of a persistent white dominance in the state's institutions, in France the refusal to recognize the inherent racism of its institutions (including academic and cultural institutions such as museums and theatres) is bald-faced. Étienne Balibar has perspicaciously defined racism as "a mode of thought [his emphasis] by which we should understand a manner of attaching words to things, but more significantly words to images, to stories, in order to make concepts." It is a definition that will serve us well in the subsequent reflection on institutional racism.[8]

Françoise Vergès in a searching essay on the struggle to decolonize the arts, relates both the nature and the scale of the problem of cultural institutions' denial of their dominantly white vision. She discusses the narrating and mapping out of the past in museums where "nothing is totally false, but the story is studded with blind spots which construct a mutilated narrative and cartography." Thus are narratives gradually rubbed out, since "erasure operates through pedagogical discourse which relates a history which in itself is not inaccurate, but which is based on concealments which in turn naturalize omissions."[9] For Vergès, while lip-service may be paid to notions of diversity, institutions remain fundamentally unchanged:

For a number of years, institutions, without changing their structure, have started organizing forums, debates and exhibitions on notions of diversity, hybridity, creolization, decolonization. Should that not give us cause to rejoice? Certainly some progress has been made. Africa has become the new object of fascination and of "discovery" for the art market, which for the artists translates into an enhancement of the value of their works and a financial support which is difficult to ignore. This said, for me, it does not add up to a decolonization. For one thing, there is often a domestication of the works, emptying them of all radicality, and for another, the structural organization of institutions and the production and diffusion remain unchanged.[10]

In France, writes Vergès:

The opposition of French cultural castes to their own decolonization is profound….From the refusal to consider a project because it "won't interest the general public" to remarks on the colour of one's skin, a forename, an origin (real or supposed), a religion (real or supposed), from the assignation to dominantly negative roles for Blacks, Asians and North Africans, from the universalism afforded to White women and men who are permitted to play any role they wish, from the assuredness with which artists draw on colonial images to construct their artistic installations to straightforward appropriation, from the absence of non-Whites in leadership positions in artistic and cultural institutions to the absence of colonial history or the critical theories of visual and postcolonial studies in France's art schools; from cartels in the museums which practise either understatement or elision or omission of the African, Asian or Arab presence in France's cities, the list is long, examples occur daily, and discriminations are proven.[11]

But all that pertains just to France, does it not? Things are very different in multicultural Britain, aren’t they? And isn't the issue of decolonization irrelevant to, or at least peripheral to, displaying and teaching China and "things Chinese" in the UK? No, on both counts.

Although British dominant culture does not subscribe to the notion of universalism, most of the points made by Vergès will still strike a chord with many an artist, creator or actor working in the UK. Ask any British actor of Chinese heritage about "Yellow-facing" in the entertainment industry. As to the question of decolonization and China/Chineseness, our representation of China as a malevolent superpower, as a military competitor, as the oppressor of Hong Kong, as an ally of autocratic regimes, may justify the Chinese regime's existence as the ever-present object of our social scientific gaze, while elevating China's avant-garde artists to rock star status may make the good times roll for the global art market. However, these meta-representations of "China" also efface the reality of the colonialist nature of Britain's historic relationship with China and British representations of Chineseness.

But are we not beyond the unpleasant moment of colonialism? No, Vergès, like Stuart Hall, makes clear we are not living in a moment after colonialism. For Stuart Hall, despite the heralding of the post-colonial moment we find ourselves simultaneously both in its continued workings and in its aftermath: "In the case of the colonial and the post-colonial, what we are dealing with is not two successive regimes, but the simultaneous presence of a regime and its after-effects."[12]

For all of us, then, the project of decolonization requires constant effort, an effort described eloquently by Françoise Vergès:

To decolonize is to learn to see all over again, transversally, intersectionally, to denaturalize the world in which we evolve, a world manufactured by human beings and their political and economic regimes. To decolonize is to learn to lay out the pieces like a puzzle and to study their relations, their circulations, their intersections. Thus new cartographies emerge which question the European narrative….[13]

Our Chinese communities, just as our Caribbean communities, are the living traces of nineteenth and twentieth-century British imperialism. It is those "Chinese" communities, fragmented, diverse in themselves, multi-lingual, part-White, unWhite that constitute the "legacy" of British colonialism, as do the recent migrants from Hong Kong, the embodiment of Britain's territorial colonising presence in its most concentrated form up to 1997, and its colonial ideology and policies that have left behind a legacy of desolation.

Thanks to the efforts of actor-activists, some headway has been made in alerting dominant white society to issues of representation of those who "look Chinese".[14] And yet, there is a long way to go before justice is done to the Chinese British and other ESEA communities. For them, decolonizing British society concretely requires (i) the recognition of their say in the definition and framing of Chineseness, and (ii) their access to the full panoply of roles in British society: as entertainers, as elected politicians, as artists, as newscasters and more.

The current landscape is messy, complicated, fragmented. It is inevitably so, since fragmentation and unwhole hybridity are constituent of the aftermath of colonialism: "Decolonization is not an acquisition, it is a process."[15]

For white readers of this article, I leave the last word to Françoise Vergès: "Be troubled, be perturbed, take the time to reflect."[15]

Gregory B Lee is Founding Professor of Chinese Studies at the University of St Andrews. He was formerly Professor of Chinese and Transcultural Studies & Director of the Institut d'Études Transtextuelles et Transculturelles (IETT), University of Lyon. His interests are Critical Theory, Cultural History, Diaspora Studies and the Migration of Ideas. His most recently published book is China Imagined: From European Fantasy to Spectacular Power (2018).You can follow him on Twitter: @GBLee

[1]See Gregory B. Lee, Chinas Unlimited: Making the Imaginaries of China and Chineseness, London, Routledge; Honolulu: Hawaii University Press, 2003; and China Imagined: From European Fantasy to Spectacular Power, London, C. Hurst & Co., 2018.

[2]https://postcolonialpolitics.org/chinesevirus-racism-behind-covid-19/

[3]Étienne Balibar, La crainte des masses: Politique et philosophie avant et après Marx, Paris, Galilée, 1997, 346. "…toutes les communautés sont imaginaires: mais seules les communautés imaginaires sont réelles." 347. All translations in this article are by Gregory Lee.

[4]See Lacy, Michelle, and Lili Man and Jessie Lim (eds), Exploring Our Chinese Identity. London: Lambeth Chinese Community Association, 1992.

[5]Pierre Bourdieu, Sur l'État, Paris, Seuil, 2012, 565: "domestication des dominés. Ce n'est pas moi qui le dis, je cite Max Weber."

[6]Stuart Hall with Bill Schwarz, Familiar Stranger: A Life Between Two Islands, London: Allen Lane/Penguin Random House, 2017, 21.

[7]Hall.

[8]Balibar, 347.

[9]Françoise Vergès, "Décolonisons les arts ! Un long, difficile et passionnant combat," in Leïla Cukierman, Gerty Cadbury and Françoise Vergès (eds), Décolonisons les arts !, Paris: L'Arche, 2018.

[10]Vergès, 123.

[11] Vergès, 126-127. Universalism – the notion that all avenues, all representations are freely open to all regardless of sex or colour.

[12]Hall, 24.

[13]Vergès, 120.

[14]See for instance, the campaigning work of Daniel York Loh, Rebecca Boey, and the entire network of activists who aim to "empower, educate and embrace East and South East Asian (ESEA) communities in the UK", https://www.besean.co.uk/ See also the Esea Inline Community Hub directed by Diana Yeh, https://www.eseahub.co.uk/

[15]Vergès, 133.

[16]Vergès, 133.

The author, Gregory B. Lee, owns the copyrights to the three images published in this article.