Rodrigo R. Duterte's victory in the 2016 presidential elections signalled the beginning of a significant shift in the Philippines' foreign relations. Duterte introduced and pursued an "independent foreign policy" designed to reduce his country's reliance on its long-standing treaty ally and erstwhile coloniser, the United States of America (US). Within the framework of this independent foreign policy, Duterte’s objectives extended to the establishment of robust political, economic, and cultural ties with non-traditional partners, particularly states lying outside the purview of the US-led international order, i.e. Russia and China. This quest for an independent foreign policy was ingrained in Duterte’s vision of a more multipolar world order, enabling the Philippines to diversify its global partnerships, unshackling itself from the dominance of the US and its western allies.

However, Duterte’s foreign policy shift collided with an ongoing maritime and territorial dispute with China in the South China Sea (SCS). He sought to mend the strained ties between the Philippines and China, a relationship that had soured during the tenure of his predecessor, former President Benigno Aquino III. This intention was evident during his state visit to Beijing in October 2016, just months after his inauguration as president. More importantly, it was on this occasion that he abruptly declared the Philippines' separation from the US both “militarily and economically,” underscoring his ambition to pursue a more independent foreign policy.

Consequently, Duterte’s foreign policy shift incurred costs to the Philippines’ claims and position in the SCS despite its notable victory against China in an international arbitration case in July 2016. It also came at the cost of straining its historical relationship with the US, with whom the country had signed the Mutual Defense Treaty (MDT) in 1951. Nevertheless, despite the ambiguities within its scope and provisions, The MDT continues to offer the Philippines with a security umbrella and serves as a deterrent against (potentially) detrimental Chinese activities in the highly contested SCS.

Furthermore, it is important to consider Duterte’s distinct background as a political outsider from the southern Philippine island of Mindanao. This island bears a long history of resentment towards both Manila (the seat of the Philippines’ national government) and the United States. It was subjected to colonial campaigns and more recently, has been tussled with a sense of marginalisation and neglect by the national government based in Manila. Duterte’s identity and ties to Mindanao further reinforced his resoluteness to chart an independent foreign policy that resonates with the sentiments of many Mindanaoans. His quest embodied a daring attempt to address historical grievances and rectify the imbalances in the country’s political landscape, where Manila, and historically, the US held significant influence. These factors then left Duterte with the intricate task of carefully balancing the intricacies within the Philippines' foreign policy landscape, much like walking a tightrope.

On the other hand, despite Duterte's unwavering commitment to pursuing an independent foreign policy, critics contended that it lacked clarity and direction. They viewed it as nothing more than an instrument to antagonise the West while appeasing China with the hopes of securing trade concessions, investments and development aid from both the Chinese government and people. While there may be some validity to this argument, it is crucial to delve into an assessment of both the intended and unintended benefits and costs of Duterte's independent foreign policy agenda. This approach provides a platform for analysing whether the advantages outweigh the disadvantages or vice versa.

Succinctly, Duterte's independent foreign policy agenda disrupted historical ties between the Philippines and the US, while being deeply intertwined with a complex interplay of regional identity, a vision for a multipolar world order, and the pressing territorial and maritime issues in the SCS. This multifarious approach has captured significant global interest and scrutiny, underscoring the intricate trade-offs and complexities inherent in Duterte's foreign policy strategy.

Given this, I aim to address the following inquiries in this article: (I) What motivated Duterte to adopt a different foreign policy approach amid an ongoing maritime conflict in the South China Sea?; (II) What were the challenges that Duterte and his administration faced while pursuing an independent foreign policy? (III) Did the Philippines benefit from Duterte’s pursuit of an independent foreign policy? The article draws primarily on literature shared to the author by Dr. Rommel Banlaoi, a former deputy national security adviser-designate to Duterte’s successor, Ferdinand Marcos Jr. and other relevant literature on the topics mentioned.

I. Duterte’s Foreign Policy Shift: Driving Factors

1. Driven By His Past: Duterte’s Identity as a Mindanaoan

Duterte's independent foreign policy agenda is partially influenced by his personal experiences. Unlike most of his predecessors, who were also born to a political dynasty, he stands apart as the first Philippine president to hail from Mindanao, a Muslim-majority area in a predominantly Christian state, that remains resentful towards US colonial campaigns (Banlaoi 2016; Parameswaran 2016). Trefor Moss (2016, 5), writing for the Wall Street Journal, noted how Duterte’s grandmother, a Muslim, played a formative role in shaping his views; sharing stories about the atrocities committed by the US during its invasion and colonisation of the Philippines at the turn of the 20th century.

More so, Duterte’s antagonism towards the US reached new heights when he began his university studies in Manila. He studied politics at the Lyceum of the Philippines University, under the tutelage of the now deceased Jose “Joma'' Sison, who founded the Communist Party of the Philippines and subsequently initiated an armed uprising against the Philippine government that has persisted since 1969. Sison, like Duterte’s grandmother, imparted similar, if not, more profound anti-American imperialist and anti-elitist values to Duterte, who, for the most part, has embraced and incorporated them into his political outlook throughout his career in public service (Moss 2016, 5). On one occasion, Duterte himself uttered “If I make it God-willing to the Presidency, I will be the first Left President in this country” (MINDANEWS 2016).

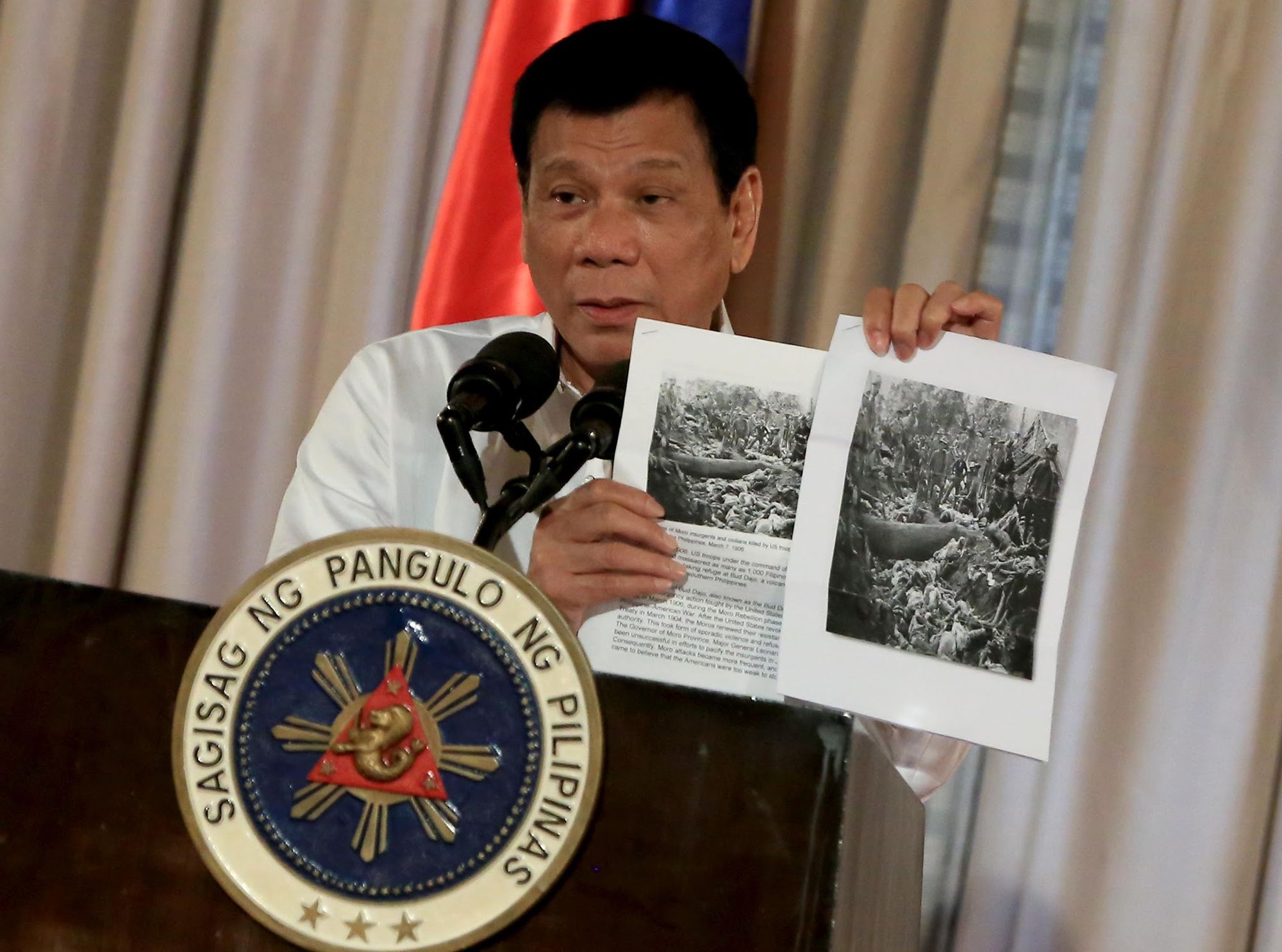

Notably, Gordon Chang, author of “The Coming Collapse of China,” highlighted Duterte’s unchanging views about the US throughout his term as president. Chang (2017, 52) emphasised that Duterte routinely condemns the US government’s role in the Bud Dajo massacre of 1906 and genuinely believes that Washington has yet to make amends for this specific act of brutality or any other instances of torment inflicted upon Filipinos, including the subjugation of his country (Chang 2017, 52).

Ironically, Duterte continues to rant and rave about an incident he considers to have been an affront to the Philippines’ sovereignty. In 2002, an American, Michael Meiring, a self-described treasure hunter with suspected ties to the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) accidentally detonated an explosive device in his hotel room in Davao City. The explosion resulted in serious injuries and property damage. As authorities were preparing to charge Meiring with the illegal possession of explosives, a group of US government operatives discretely extracted him from a Davao hospital, transferred him to another hospital in Manila, and then transported him back to the US (Philippine Star Global 2002).

Speaking on the condition of anonymity, a Philippine security official even claimed that these US agents brokered a deal with the hospital administrator to release Meiring in exchange for a US work visa for the administrator's daughter (Gajunera 2016). Duterte, who when the incident occurred was serving as the mayor of Davao City, maintains that he remains unaware of Meiring’s true identity and that the US embassy in Manila has yet to provide him with an explanation and apology (Arguillas 2016).

2. Driven By His Discontent With The US Government

Aside from his upbringing and personal experiences with the US government, Duterte's independent foreign policy agenda can also be attributed to his dissatisfaction with what he views as the US government’s fruitless attitude towards the Philippines' domestic and international affairs. He described the US as hypocritical and unreliable for its failure to carry out its time-honoured obligations stipulated under the MDT of 1951 which require the US to defend the Philippines’ territorial integrity in the event of “armed attack” and cited that the US has failed to carry out said obligations on numerous occasions.

The past and present trends in Philippine-US relations substantiate Duterte's view of the US as hypocritical and unreliable. In fact, the US abstained from taking military action against the Chinese for its occupation of the Philippine-claimed territory, Mischief Reef in 1995, and announced through its Department of State that it “takes no position on the merits of the competing claims in the South China Sea” (Dvorsky 1996,1; Guan 2000: 208; Southgate 2019, 167). Fast forward to 2016, the US announced that it would continue to maintain its neutrality over the SCS conflict despite the invalidation of China’s historical claims, symbolised by the ‘nine-dash’ line which appears on official Chinese maps by an arbitral tribunal in the Hague (Baviera 2016a, 202-203; Chang 2017, 57). In an interview with Rappler in October 2015, Duterte, then still serving as Davao City mayor, voiced his disappointment that Washington took no action in light of China’s territorial expansion, which weakened the Philippines’ claims and position in the SCS. “America did nothing. And now that it is completed, they want to patrol the area. For what? Is America going to finish the world?” Duterte asked.

Lastly, another source of dissatisfaction for Duterte stems from the US government’s levelling of human rights violations against Duterte’s infamous ‘war on drugs’ initiative. Duterte believed that the US government was in no position to censure his counter-narcotics policy as the Philippines ”long ceased” to be its colony and stressed that he only answers to the Filipino people who elected him as president (Lacorte 2016). At one point, Duterte even resorted to using foul language against his then US counterpart, former president Barack Obama, and issued a threat that he would do the same if Obama were to raise the subject of human rights violations during their meeting at a regional summit in Laos (BBC 2016). Ultimately, Obama decided to call off his meeting with Duterte (Gayle 2016).

3. Driven By The Perceived Practical Need to Mend Ties with China

The final impetus behind Duterte's pursuit of an independent foreign policy is rooted in his perception that the Philippines would benefit more by shifting away from the adversarial stance inherited from his predecessor Benigno Aquino III. This prior approach, reinforced by the Philippines' victory in an international arbitration dispute against China in July 2016, contributed to the intensification of tensions in the SCS (International Crisis Group 2021: 7). By doing so, Duterte effectively managed to apply his own ‘hedging strategy’ that is directed towards repairing strained relations between the Philippines and China in the hopes of enhancing economic ties. Notably, Duterte expressed his interests in aligning the Philippines with China’s massive Belt and Road initiative (BRI), as he felt that it could provide the country with much needed economic assistance to meet its national development objectives (Banlaoi 2022, 141; Jones 2016, 28). Simultaneously, he maintained political engagements with the US and its western allies.

Duterte has announced on numerous occasions China’s potential to be a reliable partner and was apprehensive about “flaunting” the Philippines’ 2016 legal victory given the possible security implications it could entail (Esmaquel II 2016; Gloria 2021). He expressed that such bravado might undermine Philippine security in the region, not least, that of Filipino fishermens’ operations in the SCS, and of the Philippines government’s oil and gas exploration initiatives (Banlaoi n.d.107).

With China’s declaration of the Philippines 2016 legal victory as “null and void” another layer of complexity to the relations between the two countries was added, implying that the Philippines could not solely rely on a legal approach; instead, it needed to shift its focus towards pragmatic diplomacy and confidence-building measures (CBM) to effectively address the situation in the SCS (Baviera 2016b: 23; Phillips, Holmes and Bowcott 2016). This should not come as a surprise as political scientist Graham Allison (2016) highlighted the historical pattern where no permanent member of the UN Security Council (notwithstanding China), had ever fully abided by a ruling from an international court, especially in matters concerning the Law of the Sea (LOS). He emphasised that China was observing a precedent set by other great powers over decades.

II. The Challenges Behind Duterte’s Independent Foreign Policy Shift

Duterte’s quest for an independent Philippine foreign policy was not easy. From his predecessor, Aquino III, he inherited the responsibility of safeguarding the Philippines' maritime rights and interests, particularly in the SCS (Baviera 2016a, 202). This was especially challenging because of the aftermath of the Philippines’ victory in the 2016 international arbitration dispute, which China had repeatedly rejected, declaring it ''naturally null and void” (Phillips, Holmes and Bowcott 2016). Furthermore, China’s continued expansion of its policy of ‘creeping assertiveness’ within the disputed waters of the SCS has created a challenging geopolitical landscape for Duterte to navigate (Heydarian 2018). With that, Duterte, according to the late University of the Philippines professor, Aileen Baviera (2016, 203), was faced with two main foreign policy challenges: (1) Managing the Philippines’ relations with China in the aftermath of the 2016 the Hague ruling; (2) Outlining the role of the Philippines’ military alliance with the US as the South China Sea dispute enters a new phase.

1.Managing Relations with China

As mentioned earlier, Duterte was keen on mending ties with China, which he considered to be a potentially reliable partner. Throughout the 2016 Philippine presidential electoral campaigns, candidate ‘Mayor Duterte’ (as he was commonly referred to), already emphasised the need for a practical and pragmatic approach towards engagements with China, stating that he could speak “more frankly” with Chinese government officials than with their American counterparts (Baviera 2016a, 203; Lacorte 2015). In a 2016 interview with the Manila Standard, Duterte reiterated his openness to engaging China through bilateral negotiations and the joint development of natural resources. In the same interview, Duterte also suggested that he would tone down the Philippine’s sovereignty claims in the South China Sea, but only if China reciprocated by refraining from asserting its own sovereignty over the disputed waters. In short, Duterte opted for a more pragmatic approach, whereby China was provided a role in supporting the development of the Philippines’ economy (Baviera 2016a, 203).

In October 2016, just months after assuming the presidency, Duterte made good on his earlier promise to engage China in a programmatic and practical fashion by flying to Beijing for an official visit (Hunt, Rivers and Shoichet 2016). While in Beijing, Duterte had a major meeting with Chinese president Xi Jinping, where both leaders agreed to settle their differences in the SCS peacefully, particularly through bilateral dialogues (Banlaoi 2021, 3). Moreover, it was during the same period that he declared his country’s “separation” from the US, both militarily and economically, thus disrupting the Philippines’ long standing relationship with the US (Banlaoi 2020, 100). As a byproduct of Duterte’s “milestone visit” to Beijing, both the Philippines and China formally established the Bilateral Consultative Mechanism (BCM) on the SCS in 2017 to peacefully settle their disputes and bolster cooperation and friendship amongst each other (Banlaoi 2021, 3; Fook 2018, 2). According to Banlaoi (2021), the BCM provided an effective avenue for open and productive talks, enabling both sides to express their perspectives and concerns, which proved useful in calming tensions, not only within Philippine-China relations, but also in the broader context of the SCA.

On the other hand, despite its achievements, the BCM was strongly opposed by the Filipino public, mainly because of their perception that China had “hijacked” the bilateral agenda (Banlaoi 2021, 6). In addition to this, the Filipino public hold immense “anti-China” sentiments, owed to their understanding that cooperating with China undermines the Philippines territorial rights in the disputed SCS (Mangahas 2020, 8). The reports of Filipino fisherfolks being harassed by Chinese coast guard personnel also contribute to these sentiments (Viray 2018). What is more, is that this reality poses a serious challenge for future Philippine presidents who wish to pursue policies that aim to enhance amity and friendship with China (Banlaoi 2021). Over and above that, the BCM fails to take into account the “bigger picture” behind tensions in the SCS, given the involvement of other claimant states, as well as the vested interests of extra regional powers, particularly the US, which strongly advocates for the promotion of the freedom of navigation in the high seas, and the exploration of oil and other natural resources in the SCS (Banlaoi 2021, 6-7).

2.The Role of Philippines-US Military Alliance in the Changing SCS Geopolitical Landscape

Despite his view of the US as an unreliable partner, Duterte believed that the US plays a vital role in maintaining the balance of power in the Asia-Pacific region, as well as providing the Philippines the opportunity to meet its territorial security requirements (Banlaoi 2022, 151; Baviera 2016a, 204). Duterte acknowledged this, by stating, “We can’t fight a war with China because we don’t have arms, so, we’ll be forced to ask the help of the United States because that’s the only force that has the capability to fight the Chinese, but we don’t want to do that, that’s why we’re asking the Chinese not to make any trouble” (Lacorte 2015). Moreover, the US appeared to be unfazed by Duterte’s anti-American rhetoric, citing its commitment to a series of defence agreements established with the Philippines, including but not limited to the Mutual Defense Treaty (MDT) of 1951, the Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) of 1997, and the more recent Enhanced Defence Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) of 2014 (Banlaoi 2022, 151-152).

Banlaoi (2022, 151) highlights that the significance of the Philippines' geographic location is central to the US' Indo-Pacific strategy, which is focused on promoting a free and open Indo-Pacific (FOIP). This, in turn, underscores the US' commitment to the Philippines' territorial defence and security. Notwithstanding these realities, Duterte's ability to navigate the challenges did not impede him from adopting a more calculated policy posture towards the South China Sea. This marked a clear departure from the stance taken by his predecessor, Benigno Aquino III, who placed a higher priority on obtaining guarantees from the US government regarding its defence obligations to the Philippines (Baviera 2016, 204). In the end, it appears that Duterte has resorted to a hedging strategy that involves engaging China diplomatically and economically, while enhancing the quality of the Philippines’ security relationship with the US (Banlaoi 2017, 359).

III. The Benefits and Costs of Duterte’s Independent Foreign Policy

As stated in the initial part of this work, Duterte’s alteration of the usual trajectory of the Philippines’ foreign policy was met with criticism. Critics argued that Duterte’s foreign policy mainly sought to antagonise the West, while pivoting to China with the hopes of securing financial and economic assistance from the Chinese government (Talamayan 2019, 5). This section will elaborate on the benefits and costs incurred by Duterte’s independent foreign policy agenda.

Benefits

According to Jeremie Credo (2017), a researcher at the Philippines’ Foreign Service Institute, Duterte successfully fostered robust political, security, cultural and economic relationships with countries in Asia and the Middle East within the first two years of his term. These engagements, albeit, non-traditional, not only solidified bilateral ties but also exemplified his commitment to pursuing an independent foreign policy agenda (Credo 2017). Credo goes on to state that the diversification of the Philippines’ partnerships took into account the growing interdependence amongst states and at the same time contributed to the Philippines’ domestic and international interests (Credo 2017). Duterte’s visit to Israel for instance opened the Philippines’ security and military forces access to Israel’s well-regarded arms industry (Al Jazeera 2018). This visit can be seen as a strategic response to the US government's ban on the sale of weapons that was owed to concerns over purported human rights violations cases in the Philippines (Zengerle 2016). Similarly, Duterte's visit to China played a pivotal role in not only calming tensions between the Philippines and China that had arisen due to the SCS conflict, but also fostering the growth and development of the Philippines' economy and tourism industry. In response to Duterte's visit, president Xi Jinping reciprocated by encouraging increased Chinese investments and tourism in the Philippines (Banlaoi 2020, 102 & 104).

Costs

However, while Duterte’s independent foreign policy agenda advanced the Philippines’ domestic and international interests, it also incurred costs. These costs primarily stemmed from Duterte's belief in the practical necessity of repairing damaged ties with China. Duterte downplayed the Philippines 2016 international arbitration victory, referring to the tribunal’s decision as just a “piece of paper,” (CNN Philippines 2021). In doing so, strikingly, he echoed the dismissive stance of the Chinese government, which had outright declared the Philippines’ legal victory to be “null and void”. Banlaoi (2020, 114) argues that Duterte’s acquiescence was also, in part, due to China’s promise of economic assistance, which has yet to be fully delivered. Banlaoi (2020) adds that China’s USD24B pledge failed to materialise despite the Philippines’ relaxation of its claims in the SCS. Still, the fact remains that these moves by Duterte have resulted in the softening of the Philippines’ maritime and territorial claims in the SCS.

Furthermore, despite the establishment of the BCM, China persisted in carrying out military and paramilitary operations in the SCS (CNN Philippines 202 & Limpot). Notably, China constructed numerous artificial islands, which served to consolidate its presence in the region (Huang 2022). Unfortunately, this expansion came at the expense of the Philippines, as China's actions not only encroached upon the Philippines' exclusive economic zone (EEZ), but also infringed upon other areas that the Philippines had previously claimed (Banlaoi 2020, 114;CNN Philippines 2022 & Limpot). Besides the costs on the Philippines maritime and territorial claims in the SCS, Banlaoi (2020) points out that the Philippines incurred other unintended costs as well. Duterte's visit to China led to a massive influx of Chinese tourists and workers in the Philippines, resulting in an increase in transnational organised criminal activities, including human trafficking and prostitution (Banlaoi 2020, 109). Simultaneously, Chinese workers also inundated the Philippines’ labour sector, particularly in the (offshore) gaming industry and played a significant and preferential role in China-funded infrastructure projects, sparking controversy given the implications on Filipino citizens concerning employment opportunities and industry dynamics (Banlaoi 2020, 109). As expected, these costs have turned out to be counterproductive as they have failed to alleviate the prevailing anti-Chinese sentiments among many Filipinos. Instead, they have led to a rise in cases of "Sino-phobia" and the unjust stigmatisation of Filipinos of Chinese descent (Rabena 2021).

Lastly, concerns have been raised by the Philippines' security and defence sector regarding the country's vulnerability to Chinese espionage activities and their interference to domestic affairs. This apprehension stems from the proximity of many Chinese-operated businesses, especially online gambling hubs, to critical security and military installations (Gotinga 2019). While Duterte acknowledged the possibilities that these businesses could serve as fronts for Chinese intelligence activities, he argued that “you don't even have to be near any military camp if you want to gather intelligence” (Punzalan 2019).

What Lies Ahead?

Duterte's independent foreign policy agenda was undoubtedly a transformative phenomenon that disrupted the long-standing tradition wherein Philippine presidents pursued a US-centric foreign policy. This departure from the norm brought about significant changes and symbolised a shift away from close ties with the US. Challenges and opportunities were present, both left and right, and the move opened the floor for discussions concerning the Philippine's foreign policy after Duterte. The Philippines’ 1987 constitution designates the president as the "chief architect" of the country's foreign policy, the possibility exists that since Duterte's term has concluded, the previous approach of aligning closely with the US could be restored.

In a surprising turn of events, Duterte's successor, Ferdinand Marcos Jr., a well-known political ally, has realigned the trajectory of the Philippines' foreign policy, once again bringing it back into the embrace of the United States. The shift in the Philippines' foreign policy marks a notable departure from Duterte's previous emphasis on an independent stance and signifies a renewed closeness between the Philippines and the US. This shift occurs amidst persistent tensions in the South China Sea conflict and escalating complexities that threaten stability and security in the Asia-Pacific region. The significance of an independent foreign policy for the Philippines becomes increasingly evident in this context.

The strained relations between Taiwan and China also hold geopolitical significance for the Philippines due to its proximity to them and adds to the complexity of the situation. Moreover, the recent decision to provide expanded access to the US’ armed forces at Philippine civilian and military installations further complicates matters. Some critics have accused the US of utilising the Philippines as a staging ground to advance its military and political interests in the Indo-Pacific region (Ramos 2023). It is crucial to examine these factors to gain a deeper understanding of the implications and consequences associated with the Philippines' pursuit of a self-reliant foreign policy. However, it is important to note that this article does not aim to provide a comprehensive analysis of the factors driving Duterte's foreign policy agendas but rather offers a glimpse into the underlying motivations behind his decisions.

Ignacio Valeriano, a Political Science graduate from De La Salle University in Manila, holds an MA in Politics, Development, and the Global South from Goldsmiths, University of London. With a keen interest in Postcolonial and Decolonial studies, Ignacio subtly advocates for the ideological and epistemological delinking of the Philippines from its colonial past. While currently engaged in the private sector, he is actively preparing for a career in the Philippine Foreign Service.

Bibliography

Allison, Graham. "Of Course China, Like All Great Powers, Will Ignore an International Legal Verdict." The Diplomat – The Diplomat is a Current-affairs Magazine for the Asia-Pacific, with News and Analysis on Politics, Security, Business, Technology and Life Across the Region. Last modified July 13, 2016. https://thediplomat.com/2016/07/of-course-china-like-all-great-powers-will-ignore-an-international-legal-verdict/.

Al Jazeera. "Duterte Eyes Weapons Deal on First Israel Trip." Breaking News, World News and Video from Al Jazeera. Last modified September 2, 2018. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/9/2/philippines-rodrigo-duterte-embarks-on-israel-and-jordan-trip.

Baniquet, Rey. "President Rodrigo Duterte shows images of the Bud Dajo massacre during his speech at the 2016 Metrobank Foundation’s Outstanding Filipinos awarding cer emony in Malacañan’s Rizal Hall." Presidential Communications Office – PCO. Last modified 2016. https://pco.gov.ph/photo14-091316/.

Banlaoi, Rommel. "Duterte’s Policy of Deliberate Ambiguity Towards China and U.S." China-US Focus. Last modified 2016. https://www.chinausfocus.com/foreign-policy/dutertes-policy-of-deliberate-ambiguity-towards-china-and-us.

Banlaoi, Rommel. "Post-Arbitration South China Sea:Philippines’ Security Policy Options and Future Prospects." South China Sea Lawfare (n.d.), 107.

Banlaoi, Rommel. "Benefits and Costs of the Philippines’ Paradigm Shift to China." Dealing with China in a Globalized World: Some Concerns and Considerations, 2020, 100, 102, 104, 109, 114.

Banlaoi, Rommel. "2021/51 "The Bilateral Consultative Mechanism on the South China Sea and Philippines-China Relations" by Rommel C. Banlaoi." ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. Last modified April 28, 2021. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/articles-commentaries/iseas-perspective/2021-51-the-bilateral-consultative-mechanism-on-the-south-china-sea-and-philippines-china-relations-by-rommel-c-banlaoi/.

Banlaoi, Rommel C. "Duterte Presidency: Shift in Philippine-China Relations?" The South China Sea Disputes, 2017, 359. doi:10.1142/9789814704984_0083.

Banlaoi, Rommel C. "Philippine National Security Interests and Responses to China's Belt and Road Initiative and US Indo-Pacific Strategy." Middle-Power Responses to China’s BRI and America’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, 2022, 151. doi:10.1108/978-1-80117-023-920220010.

Baviera, Aileen. "President Duterte's Foreign Policy Challenges." 2016, 202-204.

Baviera, Aileen. "Territorial and Maritime Disputes in the West Philippine Sea: Foreign Policy Choices and their Impact on Domestic Stakeholders." University of the Philippines Center for Integrative and Development Studies. Last modified 2016. https://cids.up.edu.ph/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Territorial-and-Maritime-Disputes-

BBC. "Philippine President Duterte Curses Obama over Human Rights." BBC News. Last modified September 5, 2016. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-37274594.

Chang, Gordon G. “Don’t Blame Duterte.” The National Interest, no. 149 (2017): 52–60. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26557390.

CNN PHILIPPINES. "Duterte Says PH Arbitral Win Vs. China 'just' a Piece of Paper, Trash to Be Thrown Away." Cnn. Last modified 2021.

CNN PHILIPPINES, and Kristel Limpot. "Commitments, Conflicts, Costs: PH Foreign Policy Shift Under Duterte." Cnn. Last modified 2022. https://www.cnnphilippines.com/news/2022/6/29/Duterte-admin-foreign-policy-shift.html.

Credo, Jaime. "Understanding the Strategic Importance of Duterte’s Foreign Trips." Foreign Service Institute of the Philippines. Last modified 2017. https://fsi.gov.ph/understanding-the-strategic-importance-of-dutertes-foreign-trips/.

Esmaquel II, Paterno. "Duterte: PH Won't 'flaunt' Sea Dispute Ruling Vs China." RAPPLER. Last modified May 23, 2023. https://www.rappler.com/nation/138195-duterte-flaunt-ruling-case-china-yasay-cabinet/.

Fook, Lye Liang. "The China-Philippine Bilateral Consultative Mechanism on the South China Sea: Prospects and Challenges." ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute - The ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute is a Leading Research Centre Dedicated to the Study of Socio-political, Security, and Economic Trends and Developments in Southeast Asia and Its Wider Geostrategic and Economic Environment. Last modified 2018. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/images/pdf/ISEAS_Perspective_2018_14@50.pdf.

Gajunera, F. Pearl A. "Here’s Why Duterte Hates US." Manila Standard. Last modified September 6, 2016. https://manilastandard.net/news/top-stories/215460/here-s-why-duterte-hates-us.html.

Gayle, Damien. "Barack Obama Cancels Meeting After Philippines President Calls Him 'son of a Whore'." The Guardian. Last modified September 5, 2016.

Gloria, Enrico. "The Future of Duterte’s Pivot to China: A Non-Defeatist Approach." FULCRUM. Last modified November 16, 2021. https://fulcrum.sg/the-future-of-dutertes-pivot-to-china-a-non-defeatist-approach/.

Gotinga, Jc. "Defense Chief Says Chinese POGO Workers Can Easily Shift to Espionage." RAPPLER. Last modified August 17, 2019. https://www.rappler.com/nation/237920-defense-chief-says-chinese-pogo-workers-can-easily-shift-espionage/.

Guan, Ang C. "The South China Sea Dispute Revisited." Taylor & Francis Online. Last modified 2000. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/713613514?needAccess=true.

Hawkins, Michael C.. “Managing a Massacre, Savagery, Civility, and Gender in Moro Province in the Wake of Bud Dajo.” Philippine Studies 59, no. 1 (2011): 84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42635002.

Heydarian, Richard. "Crossing the Rubicon: Duterte, China and Resource-Sharing in the South China Sea." Last modified 2018. https://www.maritimeissues.com/politics/crossing-the-rubicon-duterte-china-and-resourcesharing-in-the-south-china-sea.html.

Huang, Kristin. "Fortified South China Sea Islands Help Project Beijing’s Power: Experts." South China Morning Post. Last modified November 6, 2022. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3198504/fortified-south-china-sea-artificial-islands-project-beijings-military-reach-and-power-say-observers.

Jones, William. "Behind the Phony Arbitration Ruling." Can Nuclear War Be Averted? 2016, 28.

Lacorte, Germelina. "Duterte Warns China: Buildup to Prompt US Bases’ Return in PH." INQUIRER.net. Last modified April 21, 2015. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/686909/duterte-warns-china-buildup-to-prompt-us-bases-return-in-ph.

Mangahas, Mahar. "Filipino Public Opinion on China in July 2020." Social Weather Stations. Last modified 2020. https://adrinstituteblog.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/mangahas-public-opinion-on-china-2020_14jul_1248.pdf.

Moss, Trefor. "Behind Duterte’s Break With the U.S., a Lifetime of Resentment." WSJ. Last modified October 21, 2016. https://www.wsj.com/articles/behind-philippine-leaders-break-with-the-u-s-a-lifetime-of-resentment-1477061118.

Parameswaran, Prashanth. "Why the Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte Hates America." The Diplomat – The Diplomat is a Current-affairs Magazine for the Asia-Pacific, with News and Analysis on Politics, Security, Business, Technology and Life Across the Region. Last modified November 1, 2016. https://thediplomat.com/2016/11/why-the-philippines-rodrigo-duterte-hates-america/.

Pershing, John. "Fig.1 Bud Dajo Massacre of 1906." 1906. https://ivc.lib.rochester.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Fig.-3-Photograph-of-Bud-Dajo-massacre-National-Archives-and-Record-Adminstration-College-Park-MD.jpg.

Phillips, Tom, Oliver Holmes, and Owen Bowcott. "Beijing Rejects Tribunal's Ruling in South China Sea Case." The Guardian. Last modified November 28, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jul/12/philippines-wins-south-china-sea-case-against-china.

Rabena, Jared. "The Social Implications of Philippines-China Security Competition in the South China Sea." AsiaGlobal Online Journal. Last modified 2021. https://www.asiaglobalonline.hku.hk/social-implications-philippines-china-security-competition-south-china-sea.

Tackett, Trevor. "Preserving American Interests in Duterte’s Philippines — THE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS REVIEW." THE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS REVIEW. Last modified September 21, 2020. https://www.iar-gwu.org/print-archive/75sf2ywg0ucu28rdxp0us5cflv32dm.

Talamayan, Fernan. "Realigning a nation: Understanding Duterte’s foreign policy shift." Conflict, Justice, Decolonization: Critical Studies of Inter-Asian Societies Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3808931, 2019, 5.

Zengerle, Patricia. "Exclusive: U.S. Stopped Philippines Rifle Sale That Senator Opposed - Sources." Reuters. Last modified October 31, 2016. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-philippines-usa-rifles-idUSKBN12V2AM.