The protests that took place on July 11 in Cuba were neither convened by artists nor led by intellectuals nor conceived by a laboratory of aesthetic drives. They were popular demonstrations that evinced an extreme situation marked by political immobility, economic inefficacy, the devastating consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, growing inequality, lack of liberties and the US embargo.

This uprising, unheard of in the history of socialism, had also a cultural magnitude that is worth considering. One should not overestimate it, but underestimating it would be, in addition to a mistake, an act of injustice. For although artists did not lead the protests, several of them did join them. They did not trigger them, but they supported them as ordinary citizens. They were not the protagonists, but a few of them ended up in jail for joining the uprising. If we add to this that intellectuals siding with the government hasn’t been absent either, laying emphasis on these events as another imperialist manoeuvre evidence that the revolt has already its own chapter in Cuba’s contemporary cultural war.

Art did not take charge in leading the demonstrations, but it did anticipate them. Suffice it to cast a glance at the developments of the past year where events had taken place that exceeded the guild’s scope to have a direct impact on society. Among the best known, those started by the Instituto de Artivismo Hannah Arendt (INSTAR), the Movimiento San Isidro (MSI) or the 27N movement, stemmed from the rally in front of the Ministry of Culture at the end of November 2020. These less publicized events can be interpreted as the preamble and at the same time the testimony that culture was hitting a nerve regarding urgent issues. In turn, a network of independent or institutional publications on the island and the diaspora had taken upon themselves to report on the apogee of a new generation connected with the world and strategies to channel their dissent from it. Cubans that were born after the Soviet debacle, who can no longer stand slogans in favour of eternal socialism mixed with the implementation of a State capitalism, quite palpable and mortal, which contradicts what it preaches. It is the same generation that every day flips out on Instagram with the holly alliance between new money and the old nomenclature that has resulted in the iconographic recomposition of our tropical oligarchy.

Then as now, the government has been unable to rise to the challenge of its great paradox: that of a communist State forced to administer a society that is already post-communist. Then as now, it has chosen to entrench itself in its parallel reality and continue to offer the same answer to unprecedented situations. Hence, through repression, their interpretation consisted in dividing protesters into three unmovable categories: that of “confused revolutionaries”, that of “mercenaries” and that of “delinquents”.

Under these circumstances, the cultural clash soon intensified between those that continue to be anchored in the Cold War and those trying to break free from it. Between those who want to advance into the future with a rhetoric from the past and those that have decided to synchronize their words with a future that is already present. Among those that espouse an overdramatize Western movies’ style gunfights between a persistent Stalinism and a resurgent McCarthyism and those that conceive what happened as a national chapter of the recent global demonstrations launched against all models (including Neoliberalism, the Chinese capital-communism, the degradation of Nicaraguan Sandinismo), in whose wave it would be fitting to insert the Cuban protest. Between those that reduce the issue to an exclusive battle between Liberty and Communism, Blockade and Sovereignty, and those that consider a number of historical and current factors that do not admit such simple binary oppositions.

An example: Two days after the revolts, when the number of people arrested on the island amounted to hundreds, a Cuban-American mayor in Coral Gables had no better idea than to censor Sandra Ramos, a Miami-resident Cuban artist, on account of suspecting that she held sympathies for communism. The backlash also reached the renowned Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang, who lives in New York. “My aesthetic taste ends where communism starts”, said mayor Vince Lago, and one can’t help but wonder what he would do about Picasso.

For a long time now the Cuban issue has not been about politics – nor about the refrain on the art of the possible- but about political capital (in the sense of immediate – and cynical- profitability), which needs to turn around the unsolvable because it is precisely the lack of solutions that it profits from.

So it is no wonder that the recurrent ghost of creole anti-intellectualism would show up once again, always willing to conclude that intellectuals are to step aside from where the people are; what is the point of words when we have actions; what is the use of thinking when we have the use of action. It is time to do away with elitist shades from the ideological debate and to that end, there is nothing better than the proliferation of Fake News -Camagüey falling on July 11 and installing an independent anti-Communist government, the Castro family seeking refuge in South Africa -, as well as the vindication of “Memers”, “Influencers” and Youtubers of diverse populism, some of whom also ended up in jail (the government continues to have control over the analogue mode).

In the days following this protest that was publicized all over the world and that functions as a watershed in Cuba’s contemporary history, I perceived a certain state of shock and grief in Havana. It is as if people had internalized that the Cuban government is not going to open up, the US embargo is not going to be lifted and the world’s left is not going to understand us. “We must solve this situation on our own”

Therefore, a certain reactivation of nationalism, channelled by means of reggaeton, with the corresponding overdose of the word “patria” (homeland) blowing right and left, has its own logic.

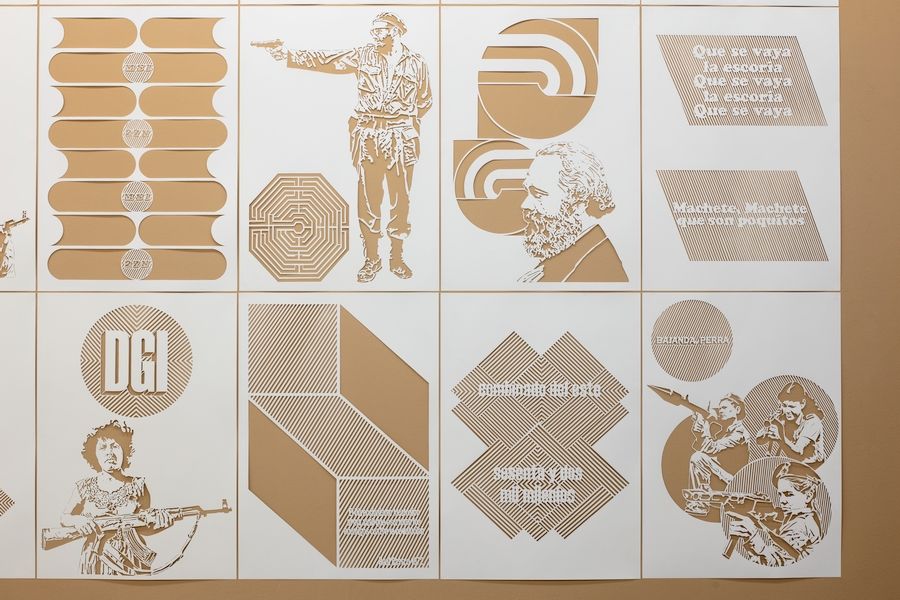

Five years earlier, during the days of the Obama era euphoria, a friend woke me up with a telephone call. He was calling from the Fábrica de Arte Cubano, where he had run into Juan Carlos Monedero, the co-founder of Spain’s Podemos, whom he had tried to convince that if he wanted to meet the future Cuban left, he should have looked for it on the streets rather than in the official circles. This young man is today one of the most solid artists of the new Cuban art. His name is Hamlet Lavastida and he has just exhibited his imposing work, Cultura profiláctica, at the KFW in Berlin.

Shortly after his return from this trip, this archaeologist of anticipation was jailed on account of incitement to rebellion. During the recent Feria de Arco in Madrid there were several demonstrations asking for his release to the extent that the last two editions of this event have been marked by Cuban art. (Let’s remember that the previous one had been dedicated to Félix González-Torres).

Just as envisaged in his work, Hamlet Lavastida anticipated his own punishment (and that of others). But in his harsh luminous series, not all the keys refer us to censorship.

In his fretworks and murals, through subtle crevices, it is possible to sense our pressing liberties.

His too.

The photograph that illustrates this article is Hamlet Lavastida’s ‘Prophylactic Culture’ (2021) at the Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin.