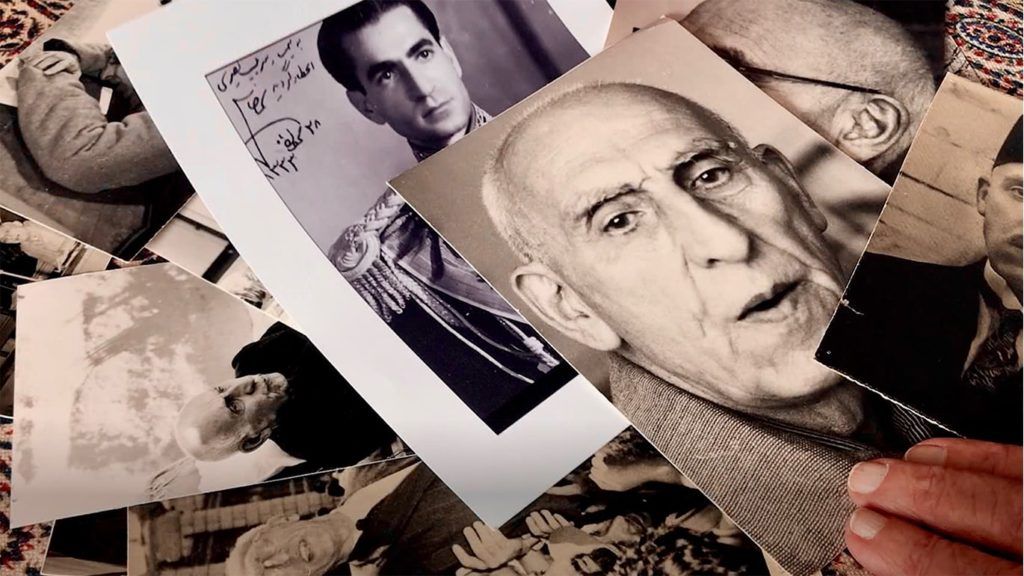

“Coup 53”, a documentary by Taghi Amirani (Amirani Media, 2019), is an extensive visual account of the removal from power of Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh in the 19 August 1953 Coup, a historical event that continues to reverberate as a theme within Iranian society.

The Anglo-American-directed operation which unseated Mossadegh has affected the Iranian political scene ever since and has been the subject of a considerable amount of attention and debate in many spheres of Iranian public life for decades.

As the 70th anniversary of the coup which unseated Mossadegh approaches, the story of the complex process which led to the August 19th events continues to attract the attention of scholars, artists and filmmakers. In recent years an abundance of academic works on the coup include dedicated monographs by scholars sympathetic to Mossadegh such as Ervand Abrahamian and Ali Rahnema; monarchist accounts by Shah-era bureaucrats such as Gholam-Reza Afkhami and Daryoush Bayandor; revisionist treatments such as the one prepared by Abbas Milani within his biography of the Shah; or extensive discussions within broader surveys of Iranian history recently prepared by Abbas Amanat, Ali Ansari and Homa Katouzian. The number of film projects devoted to the coup is relatively limited. COUP 53 marks the first such endeavor in almost a decade after the briefer treatment by Maziar Bahari and Off Centre Productions on the coup which was broadcast by the BBC in 2009.[1]

The product of ten years of research, Coup 53 is also the most extensive of documentary film projects to date so much so that, as noted by the filmmaker at the beginning of the film, some important characters in the story, such as the veteran pro-Mossadegh political figure Hossein Shah Hosseini and Mossadegh’s guard Musa Mehran have passed away before the film was completed.

Coup 53 comes across from the outset as a personal journey. It is both an attempt to explain what happened on that fateful day in contemporary Iranian history and a chronicle of the efforts of the filmmaker and his team to uncover new and potentially revelatory material. In the latter regard, Taghi Amirani joins a community of researchers, scholars and activists who have for decades sought to find their way around the tall walls which all of the main governments involved in the Coup, namely the United States, the United Kingdom and both the pre and post-revolutionary Iranian states, have erected around relevant government and intelligence sources. For most of the two hours, viewers are treated to an insightful exposé of the limitations, frustrations, but also achievements and gains which a committed researcher encounters during work on the August 1953 coup. Amirani’s journeys in search of relevant print and visual material take him to locations as far afield as Washington DC, Manchester, North Yorkshire, Paris and Ahmadabad, the village outside Tehran where Mossadegh lived during his post-coup domestic incarceration and was eventually buried in. The directors’ repeated travels in search of evidence is testament to the intricacies of working on a topic that lacks a comprehensive set of centralized and easily accessible archival resources and is severely hampered by secrecy and restrictions imposed by all sides.

The quest to obtain a comprehensive and all-encompassing explanation regarding the coup considerably picked up pace in the past couple of decades. The emergence of adulterated but important memoirs by both American and British intelligence officials who took part in the coup in the 1980s and Mark Gasiorowski’s seminal article of 1987 based on oral interviews with surviving members of the CIA team which operated in Tehran and Washington during the coup, broke the walls of the previous official silence regarding the role of the two Western allies in the unseating of Mossadegh. The publication of Donald Wilber’s detailed history of the coup by the New York Times in 2000 heralded the start of two decades in which the CIA’s archival material increasingly made its way into the public reach, particularly through the sterling efforts of the National Security Archive in Washington and Malcolm Byrne, whose role in this regard is rightly highlighted in the documentary’s narrative. Gasiorowski and Byrne’s edited volume in 2003 was a key turning point of this phase. In 2017, the Office of the Historian of the State Department released a more complete version of the Foreign Relations of the United States volume on Iran 1951-54, the publication of which had been held up during the Obama administration due to concerns over the effect it could have had on the ongoing nuclear negotiations between the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and the West. The new documents mostly confirmed the general flow of events and gave additional insight on the behavior of some of the key actors whose role is still mired in uncertainty and controversy, such as the Grand Ayatollah Borujerdi, who is omitted from the film’s main cast of characters.

Despite the continued stonewalling by the CIA, which hardly if ever publishes a significant document on the August 1953 coup without redactions, a sizeable amount of American government and intelligence documents that are now available in the public domain have to some extent been made use of in the film. The British situation is considerably different. The lack of adequate provisions within the United Kingdom Freedom of Information Act for the release of intelligence documents and the remarkable resilience of the British Secret Intelligence Service in keeping documents related to the Coup very close to their chest has meant that no significant breakthrough has been made with regards to access to the UK documents since the 1950s. Despite rumors about the existence of a comprehensive report on the Coup prepared on the British side and stored at the Foreign Office, the mere existence of such document has never been confirmed or denied officially.

As Amirani came to realize, any attempt to seek or shed more light on the role of MI6 in the August 1953 coup in Iran must come from somewhere other than Westminster, the seat of the British government in London.

The filmmaker then encounters the abridged and then complete transcripts of the interview conducted with Norman Darbyshire – the main British agent involved in the coup. The interview was conducted by the makers of an early 1980s television documentary titled End of Empire which also focused somewhat on the Coup. The transcript find sets into motion what would effectively become one of the main motifs of COUP 53: chronicling the active attempts to track down the footage from Darbyshire’s interview and the circumstances behind his missed appearance in the documentary.

Amirani engages in a long and complex pursuit. He approaches members of the End of Empire crew, spends time and effort in obtaining the full set of the interviews conducted for the documentary from the British Film Institute only to come up short of the ultimate prize of finding the Darbyshire footage. While two crew members could not recall having filmed an interview with Darbyshire, Amirani succeeds in tracking down the cameraman who believes to have recorded Darbyshire’s interview and is led to the very room at the Savoy Hotel in London where the filming seems to have taken place.

Amirani’s way around this major limitation consists of inventively arranging for the actor Ralph Fiennes to impersonate Darbyshire and read out crucial parts of the transcript in front of a camera from the same spot in which the British spy sat at the Savoy hotel. Fiennes’ professionalism and the eagerness with which he engages in this curious project pay off, yielding as they do a dramatic, enthralling rendition of Darbyshire’s account of his involvement in the anti-Mossadegh initiative. Fiennes’ breath-taking reading is interspersed with footage produced for End of Empire but mostly left unaired. Together they provide a vivid, three-dimensional account of the British determination in ensuring that Mossadegh’s great ‘sin’, the nationalization of the Iranian oil industry, would not go unpunished. The footages portray the determination with which the British establishment as a whole and its American backers coalesced around the idea of ejecting the Iranian prime minister from power.

The extent to which the Darbyshire segment actually breaks new ground, however, is more debatable. We see Amirani paying a visit to Stephen Dorril, an academic who published in 2002 a highly critical account of MI6 covert activities across the world, particularly in the Middle East. We now discover that Dorril had received a leaked copy of the full Darbyshire transcript from an Observer journalist who had prepared an article on the End of Empire episode featuring the spy in 1984. The same transcript has also been referenced several times in Ervand Abrahamian’s The Coup, published in 2013, and is likely to be present in the archive of transcripts from the series which is housed at the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

The discussion on Darbyshire contained within Dorril’s book includes the main points recited by Fiennes in COUP 53, picking up from the continuation of the MI6 efforts from Nicosia in Cyprus following the severing of diplomatic relations with Britain by the Mossadegh government in October 1952. The main elements of Darbyshire’s recollections, namely the continuation of contact with his key Iranian agents, the Rashidian brothers, via radio, his claim that British sources delivered considerable sums to them in order to assemble the crowd which contributed to the turn of events on August 19 and his explanation of the circumstances behind the chief of police Mahmoud Afshartous’ gruesome murder are discussed in some detail.[2] Fiennes’ reading of Darbyshire’s account of Afshartous’ murder is ably mixed with footage and commentary of Bakhtar-e Emruz’s coverage of the discovery of his body. The closeup of the gruesome photographs which point to extensive torture having taken place raise serious doubts on Darbyshire’s claim that the chief of police was killed through a sudden shot fired by a soldier who had taken umbrage at Afshartous’ insults against the Shah. The question which beckons is whether the rest of Darbyshire’s recollections would withstand similar scrutiny and cross-checking.[3] Darbyshire’s at times inconsistent account could have been prepared with the intention of placing inquisitive investigators off the track.

COUP 53 carries no mention of whether efforts were made to track down relevant documents and verification of Darbyshire’s other points on the Iranian side. Most of the Iranian government and intelligence documents on the coup currently available to researchers come in the form of book compilations of material extracted from the archives of Savak, the Shah’s former secret police, and its predecessors. Over the past three decades, a unit of the Iranian Information (intelligence) ministry, the Centre for Analysis of Historical Documents, has released several thematic volumes about some of the key protagonists in Darbyshire’s narrative. The Rashidian brothers, in particular, are covered in three volumes which contain a remarkable gap: there is no document present in the collection which was prepared between 5 March 1953 and 7 April 1956.[4] This tantalizing omission is a major obstacle for obtaining a better understanding of the Rashidian-Darbyshire ties and those between the brothers and the variety of domestic actors mentioned in the Darbyshire transcript. The expenditure claims made by Darbyshire and others are also open to debate. Dorril pegged the British estimate at £700,000.[5] whereas American accounts, such as the one of Kermit Roosevelt, contain mention of a budget of 1 million US dollars having been allocated for the removal of Mossadegh but with the actual expenditure being probably considerably lower. According to an interview with Roosevelt shown in the film, no more than $60,000 USD were actually spent. The table contained on page 918 of the revised FRUS volume yields a total of 5.33 million USD, which includes the likely considerable sums provided to Zahedi for the ‘immediately necessary government expenditures’ in the aftermath of the coup.

Coup 53 provides a captivating visual portrait of Darbyshire’s testimony however, it does not provide a dramatically new account or explanation for the coup. In order to maintain the narrative focused on Darbyshire and other aspects of the British and American plotting in the run-up to the coup, the film drops any substantial treatment of the main Iranian political actors and key events in the run-up to the overthrow. Including the 9th of Esfand (28 February 1953) affair and the circumstances surrounding the clumsy referendum for the abolition of the 17th parliamentary legislature in late July 1953. The politics of Mohammad Mossadegh, particularly his hope in American support for the resolution of the oil dispute which persisted until his meeting with the US Ambassador Loy Henderson on August 18, are treated in the film in a fleeting manner. This approach ends up reproducing some clichés attributed to Mossadegh which require guarded inspection. Including the often mentioned claim that Mossadegh was the ‘first democratically elected prime minister.’ This can be criticized from a variety of historical vantage points. It effectively repeats the mythological approach devised by some sectors of the National Front of Iran in the decades following the fall of Mossadegh’s government. While Mossadegh’s track record on electoral matters does point to his eagerness and embryonic initiatives for changing electoral laws and regulations to ensure a more democratic process, the circumstances concerning the 15th-17th Majles elections cannot be described as a setting in which the prime minister was elected ‘democratically.’[6] The structure of the Mashruteh system meant that the choice of prime minister was always made by restricted parliamentary cliques, rather than society at large. While the film often portrays the period before August 1953 coup as a “democratic” one, it is worth noting that the largest and best organized political party of the period, the Tudeh Party, was banned from the political sphere and could only operate through a number of front organizations. Tudeh Party was prevented from incumbency in the 17th Majles (parliament) by the government’s suspension of the elections in constituencies such as the city of Rasht where the victory of a Tudeh Party candidate, Mohammad Ali Afrashteh, appeared certain.

Perhaps due to its eagerness to portray the overthrow of Mossadegh as an ‘Anglo-American coup’, the film Coup 53 also omits any systematic discussion of the array of domestic political and societal forces that were facing each other on the eve of Mossadegh’s unseating. The film delivers only a quick glance at the most important of them, the Tudeh Party. The Tudeh’s frequent concern about the possibility of a coup to remove Mossadegh from power, to which it became privy through its military organization, date back to the weeks following the 30 Tir (July 1952) uprising and were frequently and dramatically exposed in the party press, all the way to the eve of the Nassiri’s attempt.[7] The film also does not go over the turbulent decline of the National Front in the period following 30th of Tir (21 July 1952) uprising and the departure of main erstwhile allies of Mossadegh from the Front in the aftermath of the uprising. Our understanding of the events of August 1953 will never be complete until the gaps from the Rashidian and other relevant volumes are bridged, the record of the manifold domestic actors from the Tudeh to the clergy emerge from the current penumbra surrounding their motivations and in general, the Iranian side of the affair is dealt with in a more comprehensive manner. Only in this way will the process through which a handful of skilled and resolute British and American intelligence operatives managed to end a pluralist and unique era in Iranian modern history will be explained.

The quest to keep the narrative tightly focused on the Anglo-American operations also results in the film refraining from focusing on Mossadegh’s decision-making or on that of the multitude of domestic actors during the fateful period between the failed first removal attempt of August 16 and the successful overthrow of August 19. Mossadegh’s most consequential and fatal decision, that of ordering a ban on all unauthorized street demonstrations on August 18, is in particular completely left out of the narrative.[8] Over the years, various explanations have been provided for this decision, which resulted in the streets of Tehran being mostly empty of government supporters on the morning of August 19. The FRUS and CIA material points to the ban having been issued following Mossadegh’s meeting with the US Ambassador Loy Henderson in the late afternoon of August 18. This reviewer has, however, found evidence through the Tehran daily press that the decree ordering the ban on all demonstrations which were not authorized in advance by the military governorship was prepared in the morning, broadcast at 2pm by Radio Tehran and published in the early afternoon editions of Bakhtar-e Emruz, Keyhan and Ettelaat, hours before Henderson appeared in front of Mossadegh at 6pm. The diary entries of a key member of Mossadegh’s inner circle, Kazem Hassibi, confirm this important timing, which gave the coup plotters ample opportunity to organisze the following day’s crowd.[9] According to the account published in the Taraqi journal a few days after the coup, the security forces resorted in the heavy handed clearing of the streets, and made use of tear gas and firing bullets into the air in order to implement the military governor’s order. The Third Force activists, who were, as seen below, at the forefront of the loyalist pulling down of the royal statues the previous day, were also taken aback by Mossadegh’s order and fruitlessly asked the party leadership for advice.[10] In the words of the former Tudeh military officer Mohammad Ali Amui, “there was nothing better than empty streets for staging a coup”.[11]

The main reason behind the ban was Mossadegh’s increasing apprehension for the radical turn of his genuine, loyal supporters and of the Tudeh Party. Both flanks of the anti-Shah front had, by the morning of August 18, taken on increasingly assertive positions regarding the establishment of a republic. Two of the newspapers published by staunchly Mossadeqist political groups, the Third Force and the Iranian People’s Party, openly called for the end of the monarchy. The clandestine organ of the Central Committee of the Tudeh, Mardom, published a long CC communique which called for the creation of a “Democratic Republic”. Some of the interviews from the Oral history collection of the Research Association for Iranian Oral History (RAIOH) directed by Hamid Ahmadi which were accessed by the Coup 53 research team contain important details about the above. In particular, the testimony of Amir Pishdad, a prominent member of the Third Force movement is significant when he describes how his party reluctantly heeded to Mossadegh’s order. Pishdad’s testimony is not used in the film.

The RAIOH collection also contains information which may be used to shed new light on one of the main unresolved controversies in the existing accounts of the August 16-19 period, namely the consistency, actions and ultimate impact of the “black crowds” of fake anti-Shah activists of various stripes, particularly Tudeh. Both the various CIA veterans such as Richard Cottam and Darbyshire claim to have funded and created these fake crowds. These crowds are described within the film’s narrative as effectively having taken the lead in tearing down statues of the Pahlavi monarchs and attacking shops and public venues. However, there is also another, important side to this story, namely the plans of both Mossadegh and the arc of his genuine supporters for bringing down the statues. Hassibi recalls how the remaining core parts of the National Front including a bazaari contingent systematically engaged in bringing down the statues in order to prompt a Tudeh initiative in this regard and to join the “genuine” anti-Shah crowds who were increasingly expressing their revulsion at the Shah in the streets.[12] In another part of his RAIOH interview, the Third Force member Abbas Aghelizadeh, who is incorrectly labelled as a Tudeh’i in the film, recalls the moment in which the severed head of a monarchical statue was brought into the Third Force headquarters.[13] In sum, while the black crowds did exist, the extent to which they affected critical decision-making and took part in initiatives of their own remains open to investigation.

The classic moment in which a coup achieves success, the takeover of the radio station and the first proclamations of the harbingers of the new order, does not make an appearance on COUP 53. The exact sequence and content of the addresses of the many coup supporters who spoke on air after the radio building was taken over by them, remains unclear. No complete recording of that afternoon’s broadcast has yet been made public. The best available sources, consisting of British and American monitoring reports, are beset by reception issues.[14]

However, the latter does conclusively reveal that the radio station was taken over before the fall of Mossadegh’s residence. The fake news on some cabinet members, such as Foreign Minister Hossein Fatemi, being torn to pieces which was instantly relayed by the first speakers, particularly Seyyed Mehdi Mirashrafi, is likely to have significantly dented the morale of the remaining resistance against the coup. According to both the BBC Summary of World Broadcasts and the FBIS reports, the first pro-Zahedi addresses were broadcast by Radio Tehran at 3.33pm Iran time. Zahedi finally took to the microphone at 4.55pm. Mossadegh’s residence finally fell to the attackers at around 6pm.

The monitoring reports also reveal that two brief addresses supportive of Ayatollah Kashani were made shortly after Zahedi’s speech. An “unnamed representative of the Fadayan-e Islam” relayed Kashani’s greetings to the nation,[15] prior to the senior cleric’s son Mostafa doing the same and adding that “Mossadegh undermined the Constitution. He brought the Iranian people to misery. Not one traitor shall be spared. Long live the Shah”.[16] These interventions assist in piercing the tall wall which still surrounds Ayatollah Kashani’s role and stance in those critical hours.[17] Kashani was either actively involved in the plot, as CIA accounts imply, or opportunistically provided swift recognition for Fazlollah Zahedi’s ascendancy once much of central Tehran was taken over by the pro-Shah forces.

The film continues into the post-coup period through poignant testimonies from surviving relatives of Mossadegh and his personal physician on his last, sombre years under house arrest in Ahmadabad. The image which emerges in the film is that of Mossadegh being completely detached from the political developments. This image does take into account that the former prime minister had a role in the rise and fall of the Second and Third National Fronts, as his former ministers and associates sought to revive their brand’s faded mystique in the 1960s. The film ends with the almost obligatory reference to what are often considered to be the longer-term effects of the coup: the authoritarian entrenchment of the Pahlavi-US alliance, the overthrow of other anti-imperialist figures across the Third World, the belated removal of the monarchy in Iran through the 1979 Revolution, going all the way to the confab between Donald Trump, the Saudi monarch King Salman and the Egyptian leader al-Sisi in Riyadh in 2017.

There is no doubt that the overthrow of Mossadegh was a severe setback for the development of democracy in Iran and for the country’s promising path towards an independent trajectory in the gradually emerging post-colonial world setting. However, it would have been perhaps more pertinent to focus on the resistance to the new order in the aftermath of the coup, including a focus on the repression against the more radical supporters of Mossadegh which resulted in the death in captivity or execution of the daring journalist Karimpur Shirazi, the Foreign minister Hossein Fatemi or the Tudeh officers. A look at the circumstances behind the major post-revolutionary public commemoration of Mossadegh by his many political heirs and sympathizers at Ahmadabad in March 1979 would have well fitted the film.

The continued persistence of the Mossadegh myth amongst Iranian society and expatriate communities attests to the enduring importance of his name and deeds. Through its cinematic feel, its use of Fiennes’ acting, and graphical depiction of the some of the scenes of the clash between the royalist plotters and Mossadegh loyalists, Coup 53 delivers vivid storytelling, albeit not always accurately. It has also hopefully set the ground for future projects which will engage more with the internal dimensions of the coup whilst being recognizant of the Anglo-American scheming and might one day succeed in making use of the material which is still sealed off from the public eye in the West and in Iran.

Siavush Randjbar-Daemi is Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in Modern Middle Eastern History at the University of St Andrews in Scotland. His main research interests are the evolution of state institutions in modern and contemporary Iran and the history of the Left. He is currently preparing a study of the Tudeh Party’s attitude and analysis towards the Mossadegh era.

[1]. Maziar Bahari, “An Iranian Odyssey”, available on https://vimeo.com/72994328.

[2]. See Stephen Dorril, MI6: Inside the Secret World of Her Majesty’s Intelligence Service, Fourth Estate, 2002, p.564 for the sums passed by the prominent British intelligence agent Robin Zaehner to the Rashidians, p.578 for his account of Darbyshire’s contact with the Rashidians, p.585 for his rendition of the Afshartus murder and p.588 for his description of the Meade-Darbyshire initiative with regards to Princess Ashraf, all of which appear to be extracted from the End of Empire transcript in his possession. Dorril does not explicitly reference the transcript but has clearly extracted material from it.

[3]. The full interview transcript recently released by the National Security Archive, available on https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/dc.html?doc=7033886-National-Security-Archive contains misleading and erroneous remarks by Darbyshire, for example his claim that Mossadegh “introduced” a member of the Tudeh Party into his cabinet (p.4). Such an account has not been verified in any form by Iranian sources nor by any scholar who has worked on the Mossadegh cabinets.

[4]. Volume 1 of Rashidianha be Revayat Asnad Savak, Central for the Analysis of Historical Documents, 2000contains the replica and text of a document bearing the first of these dates on p.14 and the second one on p.15. No explanation for the reason behind such a large and significant gap is provided in the lengthy introduction to the volume prepared by the Centre’s researchers.

[5]. Darbyshire claims, in the interview transcript, to have personally spent 700,000 pounds during the coup, and also states his belief that Zaehner spent over 1.5 million pounds, mostly paid to the Rashidians, in his own failed attempt to unseat Mossadegh.

[6]. See “The Third Period” in Fakhreddin Azimi’s article on Elections in the Pahlavi period on https://iranicaonline.org/articles/elections#i for an overview of electoral practice between 1941 and 1953.

[7]. On 7 September 1952, the Tudeh emphatically warned of a impending attempt to unseat Mossadegh through its openly published daily newspaper Razm Avaran and pressed for converting such a coup into a ‘war against the coup plotters’.

[8]. This reviewer’s article on the Republican Moment of August 1953 may be accessed in the original English version on https://www.research.manchester.ac.uk/portal/files/48580296/RepublicArticle_PUBLISHER_ACCEPTED.docx and in the expanded Persian one on https://www.tribunezamaneh.com/archives/165278. Unless referenced otherwise, the discussion below on topical aspects of the August 16-19 period is mostly based on these two articles.

[9]. Hassibi’s diary entries, which shed much light on the content of the meetings between Mossadegh and his inner circle during 16-19 August have been published in the second volume of Mohammad Ali Movahhed, Khab-e Ashofteh-ye Naft, Karnameh Publishers, 1999.

[10]. Homayun Katouzian, Khaterat-e Siyasi-ye Khalil Maleki, Sherkat Sahami Enteshar, 1989, p.104.

[11]. Amui’s remarks in “An Iranian Odyssey”, at 43 minutes and 16 seconds.

[12]. Hassibi’s personal diary entry for 17 August 1953 in Movahhed, Khab, pp.814-815.

[13]. It is important to note that the only prominent Tudeh event of those days, the rally organised by the National Society against Colonialism on the afternoon of August 16 from the Cafe-ye Shahrdari (currently, the City Theatre) to Toopkhaneh Square, ended with the massive statue of Reza Shah present in the Square being left untouched. As described in detail in the August 18 issue of Niru-ye Sevvom, the pulling down of this statue, the footage of which is probably shown in the film, was the work of the anti-Tudeh Third Force activists.

[14]. The initial phase of these radio broadcasts was unscripted and chaotic. The pro-coup Atash newspaper alleges that the Mossadegh government’s radio chief, Bashir Farahmand, called a loyalist technician from the prime minister’s residence and succeeded in briefly sabotaging transmissions before ‘engineers’ within the crowd who had assembled outside the radio station succeeded in restoring service.

[15]. According to reports which appeared on pro-coup newspapers such as Atash and Dad in the days following the overthrow of Mossadegh, this unnamed person was most likely Mahmoud Shervin, a close associate of Kashani and Shams Qanatabadi who was mistakenly labelled on this occasion as a Fadayan-e Islam representative. The reviewer is grateful to Ali Rahnema for clarifying Shervin’s affiliations.

[16]. Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS) Daily Report No.162, 19 August 1953, p.QQ4.

[17]. The extensive two volume compilation of Savak documents, Rowhani-ye Mobarez Seyed Abolqasem Kashani, Centre for Historical Documents, 2000 pertaining to Kashani does not shed any light on his role during the coup. The first volume has a gap between 4 August 1953 and 12 September 1953.

Note: The author of this review appears briefly in the film whilst explaining the content of a few issues of the Bakhtar-e Emruz newspaper.