According to official accounts, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was formed on 1st July 1921, when 12 people met in a small room in Shanghai’s French concession. Western accounts differ, insisting the date was the 23rd July, and that there were 13, not 12, people in the room. Western and Chinese accounts have pretty much differed ever since, but on this they agree: July 2021 was the 100th anniversary of the establishment of the CCP. History is important in China so, from a contemporary Party perspective, their 100th anniversary, in particular, is one that must be celebrated. Looking back, they would no doubt think that they now have, in fact, a lot to celebrate. The dreams and desires that underpinned the formation of the CCP 100 years ago have, in the main, been realised. The so-called ‘sick man of Asia’ has now become the world’s second biggest economy. China was now a strong, stable, powerful, modern and independent nation-state. In other words, the early Chinese communists’ goal of national liberation and ‘saving China’ from imperialism has, more or less, been achieved. Back in 1921, when the Party was first established, no one could have imagined the China of 2021 or the way they would get there. In 1921, the pathway to China’s national liberation for the 12 or 13 communist delegates who gathered in the room in Shanghai, the only way forward, was to learn from the Soviet Union.

The Soviet revolution had, after all, simultaneously overthrown the Tsarist Russian dynastic order and fought off an imperialist invasion. As that country had achieved national liberation, the lessons for China seemed obvious. Like Russia, China had suffered a long period of dynasty atrophy. In China’s case, each defeat saw another part of the country carved off and turned into concessions and treaty ports by European imperialist powers. As anger rose, the dynasty fell, but the 1911 revolution that ended it, produced a weak, divided and internationally isolated republican government that soon degenerated into warlordism. Internally divided and impoverished, successive Chinese governments proved either too weak or too compromised to stave off imperialist aggression. This led to widespread and popular nationalist indignation in cities across China, particularly among the young, intellectual urban elite. The rallying cry was ‘save China,’ but the question was, how to do this? The iconoclastic New Culture Movement (1910s-1920s) demanded a cultural rejuvenation and a new modernist outlook to combat the foreign invaders. The May 4th Movement (1919) pushed this modernist agenda further, demanding action to save the nation from an imperialist carve up. In the pages of the journal New Youth, edited by one of China’s leading intellectuals, Chen Duxiu, the early Chinese radicals searched for a way forward to ‘save China.’ For some, Leninism, with its call for colonial peoples to rise up against imperialism in a war of national liberation, seemed to hold out some hope. It certainly influenced Chen Duxiu, who would go on to become the first leader of the CCP after the 12 or 13 delegates at the first Party conference in July 1921 elected him Party General Secretary. Yet, of the 12 or 13 delegates departing from that room on that fateful day, the world would remember only one: Mao Zedong.

As unlikely as it must have seemed at the time, it was a delegate from rural Hunan province, Mao Zedong, not the sophisticated Western educated intellectuals of Shanghai, who would take the Party forward to national liberation. In 1927, the Party’s urban-based, proletarian route to power recommended by Soviet advisors and accepted by the intellectual leadership of Communist Party in Shanghai came crashing to the ground when their erstwhile ally in the struggle for national liberation —the Nationalist Party— turned their guns on the communists. Thousands would die in this act of betrayal that left an indelible mark on the Chinese Communist Party. The Party was decimated and left with no urban safe-haven so most of the surviving city communists literally started to ‘head for the hills.’

The hill-top philosophy (上⼭思想) that developed as a result of heading for the hills and staying there changed the nature of the Party. Long years of surviving in the wilderness, dealing with peasants and adapting to their lifestyles helped forge a distinctive, hybridic and telluric form of communist modernism. This modernism would still carry the touch of science and technology as a means of ‘saving China’ but now, in order to survive, the Party needed to adapt to a peasant lifestyle. They needed to ‘learn from the people’ and to become one with the people. This involved adapting to local conditions and utilising traditional vernacular resources alongside the use of more modern scientific methods and techniques. A good example of this fusion is Traditional Chinese Medicine (TMC) which, despite the name, is more a Maoist revolutionary invention than traditional for it actually comes into being, out of necessity, during the Communist rural base camp period. As peasants joined the Party, the Chinese Party also theoretically stretched the Marxist-Leninist idea of a proletarian revolutionary vanguard to include peasants. It was the peasants’ support the communists received in the countryside that enabled them to stave off repeated Nationalist army attacks on their remote rural base camps.

It was this new appreciation of the telluric power of the peasant emanating from a strong sense of communal feeling which Maoism tapped into and transformed. As telluric power was transformed into political intensity, ‘local autonomy’ gave way to ‘national liberation.’ It was this telluric-revolutionary encounter that gave the rural communists the capacity to survive the repeated military campaigns of the Nationalist government in a way they had failed to do in 1927 when their entire urban cadre force was wiped out. Having learned the peasant ways, adapted to that lifestyle and adopted the idea of self-reliance, the communists learned to survive. This enabled the Party to survive even after the Nationalist army overran their bases and forced them to evacuate all their camps and hit the road. It was this journey that would become a legend and come to typify the new Party image.

Travelling largely on foot across 9,000 kilometres (5,600 mi) of territory from south central to north western China, the communists crossed 18 mountain ranges and forged 24 rivers, all the while fighting off attacks from, or facing pitched battles with, the pursuing Nationalist army. Few who started this journey survived, but those who did were, as Mao said, ‘like gold.’ As the legend grew so, too, did the popularity and reputation of the Party. The Long March cemented a sense that it was this sort of spirit of self-sacrifice that would save China. Fighting the Japanese and finally beating their old foe —the Nationalist Party government— in a bitter civil war, the communists recruited millions of Chinese around the banner of ‘saving China’ and, when they finally took power in 1949, they were able to announce that other than a few small vestiges of colonialism —mainly Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan— they had liberated China from imperialism.

These tellurically-inspired ideas would later be used to turbo charge the national economy in an experiment that became known as the Great Leap Forward. It was in that experiment that the limits of ‘telluric power’ became as clear as they were deadly. Tens of millions would die and, while it was a complex array of factors that produced this disaster, the hybridic mixture of modernist goals and vernacular techniques employed certainly proved to be one of the toxins. A traumatic, albeit momentary pull-back from the Great Leap followed. It led to the brief introduction of markets and material incentives which, twenty years later, with the death of Mao and the end of radicalism, became the blueprint for Deng Xiaoping’s economic reform and the beginning of the China we know today.

Where Mao’s revolution in claiming to have liberated China from capitalist oppression, regarded markets as the progenitor of capitalist values, Deng reforms treated markets as essential drivers of economic growth which were the key to making China strong. For both Mao and Deng, whether it was telluric intensity or the iron clad laws of economic science, these were means to an end. The difference was that with Deng’s reforms the stagnating state sector was being outperformed and outpaced by a rapidly emerging private sector, creating a new imbalance in which the market exerted ever increasing degrees of political power over aspects of life previously controlled or dominated by the Party. In some ways, this was predictable enough. The introduction of markets required major political reforms. The assumption of most Western commentators had been that economic liberalisation would be the inevitable precursor to political liberalisation, by which they meant, more democracy. For the contemporary Chinese Communist Party, however, political reform was always a question of balance. How to maintain strong economic growth through the increasing liberalisation of the economy while simultaneously maintaining the state and Party’s grip over the process, direction, speed and nature of that change. The result is a China, which is now strong enough and powerful enough to no longer fear imperialist incursions but which still carries historic grievances and scars that continue to inform and fuel their policy decisions. With this history as a received wisdom, for many Chinese, the question of Hong Kong, Taiwan, Xinjiang and even the South China Sea claims are not about human rights but a question of national salvation. It is a question that builds on 100 years of rhetoric that centres on saving China from Western Imperialism. Perhaps, before AUKUS leads Western forces into the region it might be worthwhile reflecting on this history. For postcolonialism, it surely also raises some uncomfortable questions.

Michael Dutton is the author of Streetlife China, the prize-winning Policing Chinese Politics and Beijing Time with Hsiu Ju Stacy Lo and Dong Dong Wu. He is a Professor of Politics at Goldsmiths, University of London.

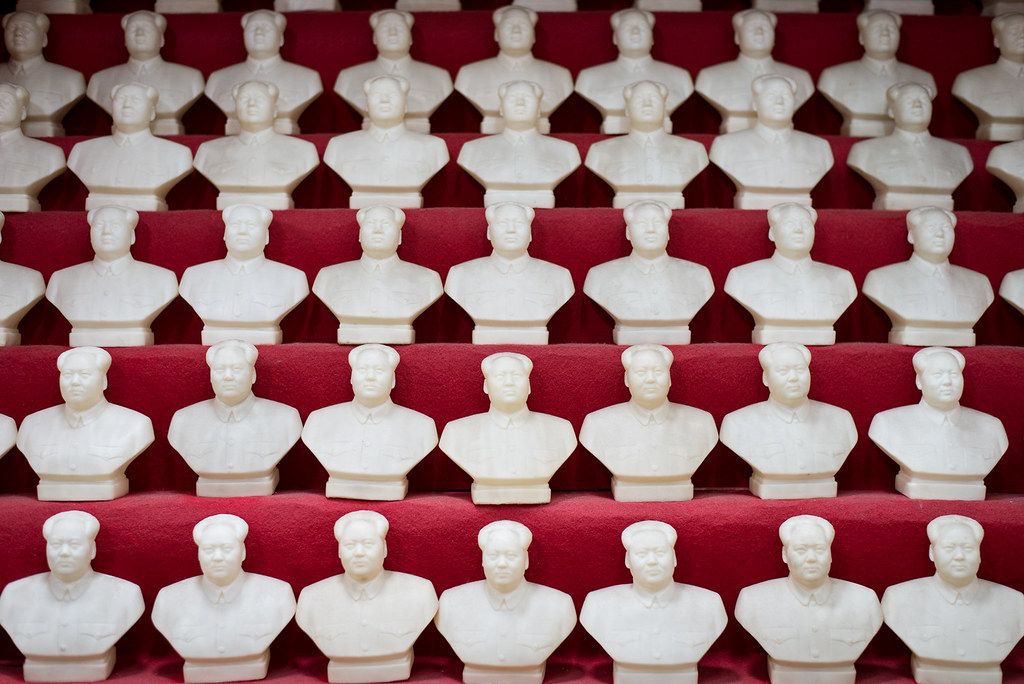

The picture that illustrates this article “Chairman Mao statues at the Propaganda Poster Museum” by Kenneth Moore Photography is licensed with CC BY 2.0.