In early 2022, years of simmering economic problems reached a boiling point and sparked a months-long wave of peaceful public protests across the island nation. The cabinet capitulated quickly, resigning en masse on 3 April 2022. The Governor of the Central Bank and the Secretary of the Treasury also quit their positions, leaving then-President Gotabaya Rajapaksha and his brother, then-Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksha, without a senior administrative team. Yet the continuous anti-government street protests persisted, despite enforced curfews, and compelled the president to flee the country on 13 July 2022. The people’s peacefully expressed frustration, desperation and anger clearly had an impact. How did this happen? What triggered this mass exodus against the Gotabaya Rajapaksha government?

The power of Aragalaya

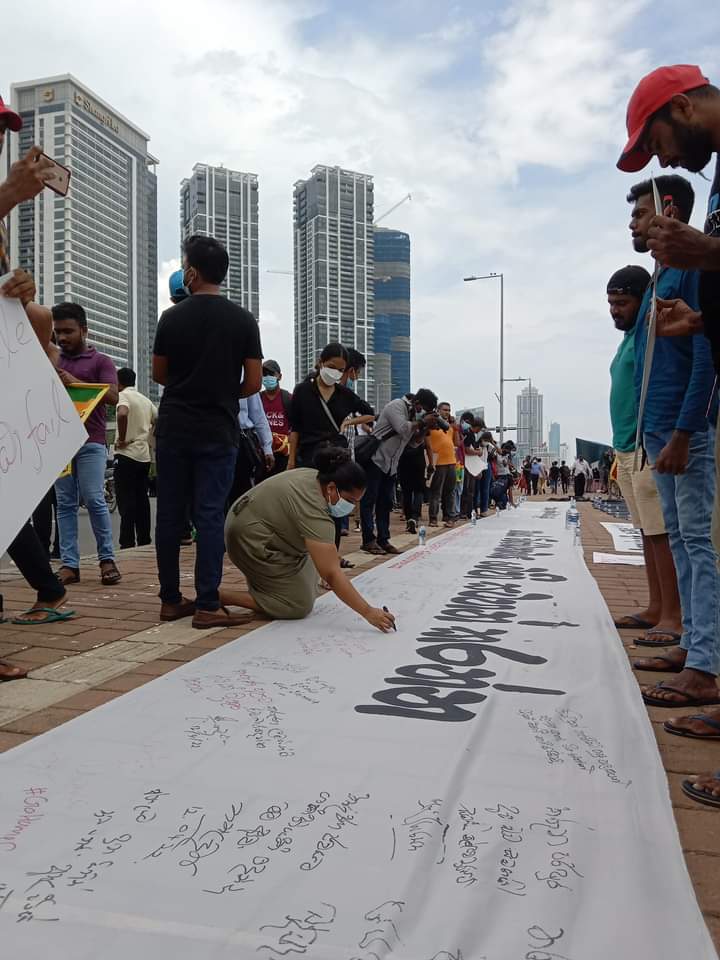

Aragalaya, which means ‘struggle’ in Sinhala, is a non-violent public protest against the inefficiency and failure of the Rajapakshas’ government[1] in tackling the country’s economic crisis. Protest sites such as GotaGoGama[2] and MynahGoGama[3]were set up as a joint effort of many civil society organizations and drew teenagers, young adults, journalists, artists, trade unionists, LGBT members, lawyers, farmers, religious leaders and many others into the protest site. For the first time ever, belonging to all strata of the Sri Lankan society became part of the Aragalaya movement. Even the upper middle classes, which tend to shy away from expressive politics, were actively present. When transport difficulties stymied efforts to create a nationwide presence at the protest sites in Colombo, Aragalaya protest sites were established in Kandy, Anuradhapura, Galle and Negombo.

Despite unrelenting pressure from Aragalaya protesters, the two remaining Rajapaksha brothers were not prepared to relinquish power. On 9 May 2022, heinous assaults launched by crowds of pro-Rajapaksha counter-protesters on activists at GotaGoGama and MynahGoGama generated a nationwide backlash that finally convinced then-Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksha to resign and clear the way for a new all-party government, yet his brother remained steadfast. On 13 May, President Gotabaya Rajapaksha gave the prime ministership to Ranil Wickremesinghe in what only can be described as a political deal. He bypassed all of his own Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) members of Parliament in favour of Ranil Wickremesinghe, the sole representative of the once-powerful United National Party. Ranil Wickremesinghe had served as prime minister on five occasions, but always at the head of a fragile coalition and never completing a full term. This new prime minister is one vote of confidence away from removal and thus in no position to defy the wishes of the president. It seems that his tasks include controlling the protests, taking the blame for any repercussions for international bail-out-associated obligations, and allowing the Rajapaksha family to return to power after a lapse of time.

In response to Wickremesinghe’s appointment as prime minister, protesters re-established NoDealGama[4] outside the prime minister’s residence at Temple trees, insisting that on the resignation of Ranil Wickremesinghe. Yet, as access to basic necessities continued to be an issue, ordinary people again began to join the GotaGoGama in late May 2022. Their numbers soared as the limited fuel supply developed into a full-blown crisis: the government acknowledged its inability to import fuel and announced its decision to provide fuel only to people who work in the essential services.

Further, 13 June 2022, the Cabinet authorized the Ministry of Public Administration (MPA) to issue a circular (15/2022) announcing that government offices would be closed on every Friday for three months, ostensibly to permit public officers to engage in cultivation and agricultural activities. Besides, all schools were to be closed and government institutions would provide only skeleton services, due to the shortage of fuel. Another MPA circular (16/2022) released on 26 June allowed the public institutions to invite minimum staff until further notice to perform the daily duties of the institution to extend un-interrupted services and permitted the staff to work remotely at all times possible.

The paralyzed economy frustrated the ordinary people of the island and the activists representing the GotaGoGama called for a mass nationwide protest against the Rajapaksha-led government on 9 July 2022. At the end of the day, protesters stormed and occupied the presidential residence and offices. Five days later, President Gotabaya Rajapaksha fled the country and quit the executive presidency on 14 July 2022. For the first time in the history of Sri Lanka, Gotabaya Rajapaksha has not utilized his executive presidential powers in its full force and became a failed president in Sri Lanka.

The president’s resignation led Ranil Wickremesinghe to be sworn in as acting president. While GotaGoGama activists demanded his resignation, Ranil Wickremesinghe formalized his mandate on 20 July, 2022, when 134 out of 225 members of parliament supported his presidency. His victory was secured when the Rajapakshas-led SLPP extended its support.[5] Thus despite his unpopularity with the public, Ranil Wickremesinghe has a legal foundation to retain in power until November 2024.

On 21 July 2022, following Wickremesinge’s formal election, protesters announced their withdrawal from protest sites at the presidential secretariat and prime ministerial residence. The following early morning, however, an unnecessary and troubling raid launched by the military left nine people seriously injured. When US Ambassador Julie Chung raised concerns about this, President Wickremesinge pointed out that these tactics were similar to those used by US security forces when protesters (Donald Trump sympathizers) took the US Capitol under their control last year. He noted that the presidential secretariat is the repository for important documents, so, on his orders, Sri Lanka defense forces removed the protesters. The quick move on the part of the new President begs the question if he is trying to fulfill the wishes of the Rajapaksha family by using executive presidential powers in full force, or if he wishes to adopt an authoritarian type of government to overcome the economic crisis that continues to overwhelm Sri Lanka. As the new president’ government anticipates, is it easy to overcome the economic crisis that Sri Lanka has been experiencing? How did this happen? Who is responsible for this crisis?

Root causes of economic crisis

There are several explanations, yet the economic crisis confronting Sri Lanka is overwhelmingly home-made and has deep roots. While Mahinda Rajapaksha has been both president (2005–2015) and prime minister (2019–2022), he is best known as the general who brought an end to the brutal, three-decade-long armed conflict with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in 2009. As president, he initiated a series of infrastructure development projects and secured loans from other countries to finance projects such as the Hambantota International Port, Colombo Lotus Tower, Colombo Port City, Nelum Pokuna Theater, and a few expressways. Yet every project served more than just the public good. For example, the Hambantota International Port project is in the home district of the Rajapaksha family. It turned out to be a huge loss for the government and now has been leased to China Merchants Port Holdings Company for 99 years. Other infrastructure projects have similarly failed to generate revenue for the government.

In 2015, Mahinda Rajapaksha lost the presidency to Maithripala Sirisena (2015–2019). Upon the electoral victory, President Sirisena formed a National Unity Government with the United National Party. This coalition sought to change Sri Lanka’s relationship with Chinese companies when it comes to infrastructure and development, and to rebuild its relationships with the US, the EU and India[6] (Sultana 2017). The relationship between politics and society took a new turn on Easter Sunday in April 2019, when individuals allegedly associated with Islam executed a coordinated terrorist attack that killed 259 people. The Rajapaksha family described the event as evidence of an Islamist threat against the Sinhalese community, which comprises a majority of Sri Lanka’s population and a stronghold of Rajapaksha political support. This, together with promises to cut taxes and hire a massive number of new government employees, catapulted the Rajapakshas back into power in November. This new government quickly made good on its promises, which may have benefited ordinary people, but not nearly to the extent they helped bigger companies and investors. They certainly led to a massive decrease in government revenue, even without considering the salaries of the 65,000 newly employed graduates who had been appointed to state sector positions by 2021[7] the question of where money to pay these new public servants would come was ignored.

The COVID-19 pandemic emerged in March 2020, just as Sri Lanka had started to recover from the Easter Attack. Nation-wide lockdowns and international border closures shattered the tourism industry. Further, remittances from overseas declined as the pandemic forced the involuntary termination of the jobs of many migrant workers. By the beginning of fourth quarter of 2020, more than 54,000 Sri Lankans had been repatriated and another 43,000 were awaiting the same fate (Weeraratne, 2021)[8]. These factors had a catastrophic effect on the economy of Sri Lanka.

While this was happening, the Import and Export Control Department imports of chemical fertilizers and agro chemicals on 27 April 2021. President Rajapaksha claimed that this was part of a new ‘green economy’ policy, but the foreign exchange crunch was already being felt and surely figured into his choice. This policy change had several impacts. First, farmers were worried about their ability to earn a living, and this worry was sufficient to bring them onto the streets. In other words, Agayalaya began with a critical mass of protesters already present. Second and unfortunately, the government ordered 99,000 metric tonnes of organic fertilizer from a Chinese company in August 2021. When it arrived in October and a sample was inspected, a dangerous bacteria was found. The company refused to order the ship to return until Sri Lankan government had paid US$ 6.9 million in compensation, which finally occurred in January 2022. This sort of poor-decision making seriously damaged both the country’s economy and President Rajapaksha’s political credibility.

All the above have contributed enormously to damaging the economy of crisis-hit Sri Lanka. It also adds critical context to an economic crisis that could, misleadingly, be boiled down to two words: foreign exchange. For reasons of bad business (entering into tempting but economically unwise international business relationships), bad management (designing projects in ways that prioritized political interests over economic efficiency) and bad luck (COVID-19), the country found itself with international obligations that exceeded its ability to pay. Most importantly, the debt mismanagement on the part of the Central Bank emptied the foreign reserves which made the import of essential supplies difficult. In today’s context, Sri Lanka has to pay back US$ 51 billion in international debt not just to China, but to other countries as well. Sri Lanka has defaulted for the first time, as it chose to dedicate its tiny foreign currency stock to importing essential supplies from other countries.

The crisis has been evolving for years and has been in full force since 2022. It has forced the country to face prolonged power blackouts and acute shortages of fuel, medicine and essential goods, due to lack of foreign currency.

The Sri Lankan government has made several kinds of efforts to get its economic house in order, but they have had a limited effect. Of most relevance to ordinary people, the Tamil Nadu state government dispatched the three rounds of relief materials (over 40000 tons) to Sri Lanka by July 2022. To address the foreign currency crisis in the first quarter of 2022, the government of India disbursed US$ 1.4 billion in general financial support and a 0.5 billion a line of credit dedicated to fuel imports to Sri Lanka. All of these, however, were ‘one time’ initiatives and, as we have seen, the crisis had not been overcome when this funding dried up. More recently, Sri Lanka has been in separate, ongoing negotiations with the IMF, USA, China and India, but an IMF bailout would require extensive structural adjustments as Sri Lanka has lost credibility in respect of repaying the international debts since April 2022. Frustratingly, the IMF has been reluctant to approve a rescue package in good time.

In short, while both Covid and international pressures exacerbated Sri Lanka’s financial crisis, its ultimate causes are domestic.The three-decade-long armed conflict and the social welfare system of Sri Lanka have specially endangered the economy for decades. Today, Sri Lanka is on brink of ruin as it has to repay a huge amount of international debt. Uncertainty in Sri Lanka may continue if political stability is not established by the new government under the leadership of Ranil Wickremesinghe.

Is Aragalaya withering away?

While Aragalaya had a massive impact on Sri Lanka’s political trajectory from March through July 2022, it is unlikely to be a major factor in the future, for three basic reasons: the image of ethnic unity has turned out to be an illusion; ideological fringe elements have attempted to capture it, and and President Wickremesinghe already has demonstrated his willingness to suppress political dissent. The first two will be addressed here, with the third reserved for the conclusion.

In March 2022, as shown above, Aragalaya successfully appealed to Sri Lankans from all ethnicities, regions, religions, ideologies and classes. These included the upper middle class, which previously had rarely been visible at protest sites. Further, in another Sri Lankan first on 18 May 2022, Sinhalese protesters from the South gathered at GotaGoGama to commemorate the Sri Lankan people who were killed during the final phase of the armed conflict of 2009. Relatives of Tamil victims also participated. Rice porridge (kanchi) at the site was prepared and served for Sinhalese protesters. Nonetheless, it appears that fears about the government surveillance mechanism have limited Sri Lankan Tamil support of Aragalaya to minimal levels.

According to M.A. Sumanthiran, member of parliament for the Tamil National Alliance, Sri Lankan Tamils ‘may want to support the current protests; they think they are legitimate and particularly the youth are coming forward to do that, but they can’t forget the fact that when this was 100 times worse [during the civil war], these people did not open their mouths’ (quoted in David, 2022).[9] Sumanthiran’s statement captures the perception of northern constituencies.Between the mid-1980s and 2009, armed conflict in Sri Lanka disrupted every aspect of the day-to-day life of Sri Lankan Tamils, something which I experienced first-hand. Sri Lankan Tamils, who comprise an overwhelming majority in Northern Province and a plurality in Eastern Province, were severely affected by the violent armed conflict. Thousands of Tamil peoples’ homes were destroyed. The military arrested many Sri Lankan Tamils on security grounds, but many others were caught up in the conflict as armed soldiers patrolled the streets. Disappearances, murders, large scale internal and external displacement, and aerial bombing of buildings are among the threads weaved into Sri Lanka’s civil war tapestry.

The final stages of the war, 2008–2009, were arguably the worst. Many people were killed and most underwent hardships due to the shortages of water and food items. There was nothing to eat, no communication with the outside world and no medical assistance. The extreme humanitarian disaster, including high levels of Tamil civilian causalities as they were forced to remain within the combat zones during the final days of the armed conflict in the Vanni region, are etched into the population’s collective memory. Even after the war ended, Sri Lankan Tamils were kept in military-run camps where, for several months, they faced further humiliations, including lack of freedom of movement; arbitrary arrests; lack of nutritious food; lack of water, bathing facilities and sanitation; lack of proper shelter; and overcrowding. Furthermore, infectious diseases including diarrhea, viral fever and chickenpox, were common in all the military-run camps, as was sexual abuse of women. With these experiences in the recent past, it is unrealistic to expect the participation of Sri Lankan Tamils from North and East in the Aragalaya. It does not mean that the people from these districts are not seriously affected by the current economic crisis. In fact, both inflation and severe shortages are all too familiar.

The second internal factor is a change in the ideological direction of the movement. Crowds at the GotaGoGama and MynahGoGama avoided partisan issues of all kinds. And, although partisan leaders supported the movement – for example, Anura Kumara Dissanayake began a three-day Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (National People’s Power) march on 19 April 2022, and Sajith Premadasa began a six-day anti-government march in Kandy on 26 April 2022. Both marches ended in Colombo, but both chose not to go to GotaGoGama at Galle Face. In this way, Aragalaya itself was able to project a non-partisan character. This changed after pro-government counter-protestors viciously attacked Aragalaya members 9 May 2022. To show their support for the victims, both Dissanayake and Premadasa visited the destroyed GotaGoGama site later on the same day. The first was well received, but the second was not. This marks the beginning of an ideological fissure in the Aragalaya movement.

A further fracture occurred on 9 July. On this evening, as the day’s events drew to a closed, members of the Inter-University Students’ Federation (IUSF), an arm of the Frontline Socialist Party, controlled the microphone and proclaimed a six-point set of demand on behalf of the whole Aragalaya movement: 1) the resignation of Gotabaya Rajapaksha 2) the resignation of the government, including Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe 3) the formation of an interim government, 4) the adoption of a new constitution 5) popular sovereignty and 6) timeframe for the implementation of the proposals by the interim government.

For three months, Aragalaya presented itself as a multi-ethnic and pan-ideological movement. Its impact on politics and society is both unprecedented and undisputed. However, the genuineness of its pan-social claim has come under scrutiny. Both ethnic and ideological tensions are weakening the movement, possibly beyond repair. While it had not begun in this way, it seems to have withered into what Ivon (2022) calls a ‘One-day People’s Revolution’ that facilitated the removal of the president, yet will not bring any major changes to the current power settings[10]. The ruling SLPP remains powerful in Parliament, as was evident in the election of the executive President for the remainder of the presidential term.

Conclusion

Since March 2022, the island has been rocked by public demonstrations calling for the immediate resignations of then-President Gotabaya Rajapaksha and his government, laying blame for this massive economic and political crisis was squarely at their feet. Upon the military victory over the LTTE in 2009, the majority Sinhalese had celebrated Mahinda Rajapaksha, the war hero who brought an end to the armed conflict during his first presidential term. Fast-forward to 2019 and we see his brother was elected as President with more than 52 % of the vote. The people were not too worried about Rajapaksha government’s corruption and cronyism. Nor were they worried about the elements of ethnic division that percolated through the campaign. And, although structural economic challenges were beginning to progress from ‘possible’ to ‘probable’, these also did not weigh heavily on the minds of voters. Instead, the people redoubled support for this famous family and its SLPP party, increasing their presence in parliament by nearly 50 per cent, to a comfortable majority, after the August 2020 elections. Nonetheless, once the economic crisis began to be felt, Sri Lankans began to question all of these issues, and Aragalaya was born.

The question now is, ‘What happens next?’ Optimists point to what appear to be good faith efforts by the Wikremesinghe regime to find ways to provide essential goods to the people. Pessimists point to likely governmental resistance to the kinds of reforms the IMF is likely to demand, and then to public expressions of anger at continued shortages. They note that, from the first day of his Presidency, the military used violence to disperse protesters who, only an hour earlier, had promised to disperse on their own. This indicates a willingness not only to use force, but also to make examples of ‘the few’ in order to cause ‘the many’ into submission. Aragalaya’s own weight and internal contradictions appear to have weakened the movement. It is weakened, but not completely powerless. While a resuscitation is possible, one worries that the more likely outcome is that what remains of Aragalaya will be crushed by a President who has demonstrated his willingness to use all of the executive authority available to him.

Malini Balamayuran is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Political Science at University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka, where she has been since 2008. She obtained her PhD in Social Sciences from University of Western Sydney, Australia and MA in Political Science from University of Hawaii at Manoa, USA. Balamayuran is co-author of recent publication of ‘The Failure of Constitution-making in Sri Lanka (2015–2019)’. Her interests lie in the area of extremism, ethnic mobilization, governance, disaster capitalism and constitution-making.

[1] It is not an exaggeration to describe the Government of Sri Lanka in April 2022 as ‘the Rajapaksha’s government’. In addition to the presidency and prime ministership, ministries of finance, agriculture, irrigation and youth and sports also were headed by Rajapaksha family members, Basil Rajapaksha, Shasheendra Rajapaksa, Chamal Rajapaksha and Namal Rajapaksha, respectively.

[2] GotaGoGama is a public protest site at Galle Face, near the Presidential Secretariat Office in Colombo.

[3] MaynaGoGama, a public protest site established outside the Temple Trees, the PM’s official residence, where people demanded the resignation of Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksha and his brother, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

[4] NoDealGama is a new protest site set up outside the Temple Trees after Ranil Wickremesinghe was appointed as the prime minister to serve the country after the resignation of Mahinda Rajapaksa on 9May 2022.

[5] SLPP member Dallas Alagaperuma obtained the support of 84 members and a third candidate, National Peoples’ Power leader Anura Disanayake won only three votes out of 225.

[6] Sultana, G. (2017) National Unity Government in Sri Lanka: An Assessment, Retrieved at National Unity Government in Sri Lanka: An Assessment (idsa.in)

[7] The workforce of state sector is approximately 1.7 million and around half of government revenue is dedicated to salaries and pensions of state-sector employees.

[8] Weeraratne, B. (2021), How Sri Lankan remittances are defying COVID-19, Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka, Retrieved at 10-East-Asia-Forum-BW.pdf (ips.lk)

[9] David, M (2022) Political and economic crisis: Family affair will continue even if 20A is abolished: Sumanthiran. Retrieved at Political and economic crisis: Family affair will continue even if 20A is abolished: Sumanthiran – The Morning – Sri Lanka News

[10] Ivon, V. (2022) Sri Lanka: What could be the end of the revolution? Guardian

Retrieved at Sri Lanka: What could be the end of the revolution? | Sri Lanka Guardian (slguardian.org)