Many claim that politics in large US cities such as New York should not be considered relevant for formulating generalizations about American politics. But the recent election of Zohran Mamdani exhibits trends and expresses potentialities suggestive of larger developments relevant across the nation. The victory of Mamdani's grass roots campaign, led largely by the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), is being heralded by some as a blueprint for the election of progressives in other areas of the country. They claim that his ability to mobilize so many volunteers and remain true to an egalitarian economic agenda proves that left politicians can be victorious without compromising their core values. While this could be true, the victory reflects trends in American politics that go beyond the viability of the DSA and Mamdani's social-democratic policy agenda. In fact, the existence of this campaign points to the potentiality of a new understanding of decentralized sovereignty that could animate socialist politics in the US. While this new conception could greatly impact both the left and American politics in general, its adoption is by no means guaranteed. Either way, its basis in political and economic phenomena beyond this campaign demand that it be at least acknowledged, if not seriously considered, as a goal to be pursued by those advocating socialism.

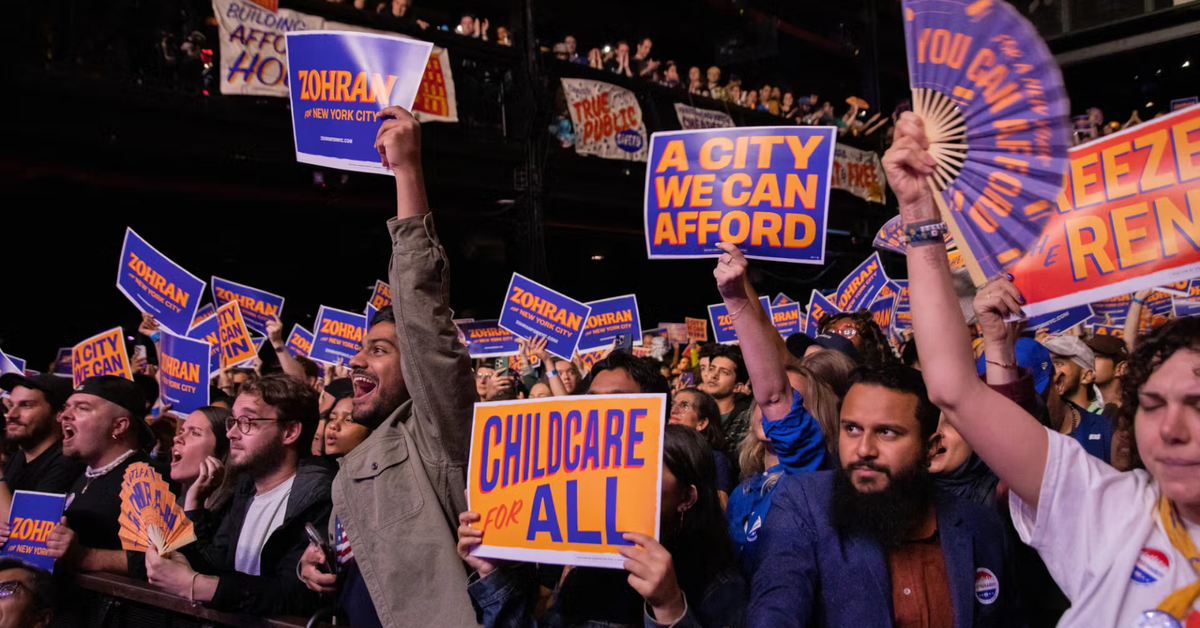

The core of the wide-spread interest in the Mamdani campaign resides in its high levels of grass roots mobilization and participation. In the general election, Mamdani received 1,036,051 votes and had 108,000 volunteers. Thus, one out of ten people who voted for him also actively participated in the campaign, a level of engagement rarely seen in US electoral politics. This volunteer army was cultivated not exclusively through a central apparatus, but instead through the volunteer network itself. Volunteers called more than 4.4 million New Yorkers and knocked on 3 million doors. Additionally, 6,568 people signed up to volunteer with the campaign when asked by a canvasser, another 8,389 when asked by a phone banker, and more than 700 volunteers “‘stepped into leadership’ and trained to be field leads.”[1] Thus, after the consternation caused by Trump’s victory just over a year ago, Mamdani's win has been welcomed by many (if not all) mainstream liberals and progressives as a demonstration of the possible power of grass roots organizing to counteract authoritarian populism.

Although the Mamdani campaign has received public admiration from many in the Democratic Party, there is some reason to be skeptical of these platitudes. US politics has previously seen an example of a powerful volunteer network in support of a Democratic candidate, one that was acknowledged to be fundamental to victory and promised to be a continuing part of the administration, only to be abandoned by that candidate nearly as soon as they were inaugurated—the example of Barack Obama.[2]

Much like Mamdani, Obama organized a group outside of the Democratic establishment, Obama for America (OFA), that deployed nearly 2 million volunteers during the campaign, a force that Obama suggested would be integral to pushing through his agenda after the election. But OFA was quickly sidelined and abandoned—as were many of Obama's more progressive stances. Christopher Edley Jr., who advocated for the continuation of OFA as a movement that would both be aligned with the administration and as a pressure group that would help pass progressive legislation, has stated that the group was disbanded because it would “have required that members of the political team who had just won the nomination be willing to cede control of the grassroots movement and turn it more in the direction of policy advocacy and progressive advocacy.”

This is the main question facing Mamdani—will the grass roots movement that enabled his victory continue to play a key role in his governing coalition? Many signs point to yes. The fact that Mamdani's volunteer network was comprised of independent, pre-existing groups and was not solely a creation of the campaign itself makes it impossible for the campaign to disband the network, as the OFA was. Additionally, members of the administration seem to be actively maintaining their links with these groups. For example, Ivan Pardo, who was fundamental to building Mamdani's volunteer network, has stressed how the campaign will continue to work with independent grass roots groups such as the New York Taxi Alliance. Maintaining relationships such as this demonstrates the campaign’s commitment to continuing a relationship with its network of activists and the groups to which they belong.

Furthermore, because of the networked and decentralized nature of the movement, participants experienced a strong sense of autonomy, energy and connection to community that stands to last long beyond the campaign. The campaign's use of volunteer staging areas, described as “temporary field offices for a campaign—either at a home, business, or public space,” “to launch GOTV voter contact activities”, though not a new approach, has been more extensive than in other instances in which they have been employed. This tactic allows volunteers without the time to actually canvas to still participate in the campaign. Chris Shay, thirty-four, a second-time host in the Bushwick section of Brooklyn, states, “I thought I had taken a disinterested state over the last few years, but in the past couple years, I’ve realized it was more of a disembodied state. Once I engaged, I realized I care a lot.”[3] Thus volunteers report the thrill of connecting with strangers, watching their toddlers play with canvassers, and coming home to find unexpected guests–this ‘embodied’ experience of political action produces deep personal changes that cannot simply be negated by the leader of the organization and will likely sustain continued engagement.

The campaign's relationship with NY DSA merits extended commentary due to both the assistance it gave to Mamdani's campaign and future tensions that are sure to arise between the administration and the group. To begin, NY DSA has grown larger, and consequently, more powerful through its involvement in Mamdani’s election. From the time when Mamdani announced his candidacy, membership has grown from about 5,000 members to over 11,000. This renewed strength has created a situation where Mamdani cannot simply abandon DSA once his administration begins, as so many mainstream politicians have done after being assisted by strong grassroots movements during their elections. Furthermore, due to its history of endorsing candidates that have won, DSA NY has experience with ensuring that politicians, once elected, do not abandon their progressive agendas. The best example of this is NY DSA's extended relationship with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Many DSA members were suspicious of whether her primary allegiance was to the more ideologically conventional Justice Democrats and what that meant for her commitment to democratic socialism. In tense moments the NY DSA and DSA National have disagreed with her decisions. Still, although DSA National has decided to rescind its endorsement, NY DSA has not, demonstrating their commitment to the relationship and their autonomy from the national organization. As one NY DSA member put it, “Our collective wisdom has decided that while certain compromises need to happen in government, the candidate will fight hard for us and our movement while communicating the reasoning behind their decisions.”[4] Whether one agrees with this decision or not, it is a testament to their commitment to AOC and complications of electoral politics in general. These tensions will surely be present during the Mamdani administration, and NY DSA has shown that it values the relationships it has with elected officials enough to make compromises on its agenda.

Thus while Mamdani most likely doesn't intend to dismantle this activist network, the tension between the desire to create a grassroots movement that propels one into office and to abandon that movement due its ability to challenge one's agenda transcends any individual politician. But the tension arises due to the nature of sovereignty in the modern state itself. The core of any modern state, its reason for existence, is the centralization of sovereignty. The existence of any grass roots movement, especially one consisting of independent organizations with their own networks of activists, militates against a centralizing tendency. For the contemporary liberal capitalist states the ideal citizen respects the rights of others, participates in regular elections, and most importantly, acknowledges the authority of the central government. Such states work to shape citizens towards this ideal. Movements such as those involved with the Mamdani campaign encourage solidarity based in the “embodiment” of face-to-face interaction, and strive to maintain political relationships outside of the logic of the state. Whereas modern states require all political action, legitimacy and ultimate decision-making be contained by institutional political spaces, such movements seek to establish their legitimacy and efficacy across multiple nodes of sovereignty sustained by independent, local associations. In practice this takes the form of horizontal volunteer networks which encourage participants to rely upon themselves and not on the state, to take hold of the power to make decisions for themselves, and to practice acting independently of official bureaucracies. Consequently, these movements and the activists come to see themselves as political forces in their own right, with agendas that they demand be enacted, and with power and political agency that extend beyond the campaigns for which they worked.

Whereas traditional, hierarchical organizations in civil society often engage in corporatist bargaining to solidify themselves as official government partners, accepting, for example,leadership positions in governing administrations, truly insurgent movements like those involved in the Mamdani campaign, with their networked organization and democratic decision-making, resist assimilation by the governing logic of the state. That the insurgency upon which a new sovereignty is found must either be ignored or crushed on that sovereignty is established, is identified by Massimiliano Tomba in his Insurgent Universality: An Alternate Legacy of Modernity,[5] as a constitutive pattern in the development of the modern state. During the French and Russian Revolutions, local, small-scale groups of citizens self-organized alongside and in tension with larger hierarchical parties and political organizations to advocate for radical political goals. Whereas Mamdani's campaign was certainly not revolutionary, it did embody a radical policy departure from current political discourse. It also gained momentum from both the threats posed by Trump's authoritarianism and the collapse of trust in so many traditional political forces—in the US, mainly the Democratic Party—but also mainstream media, many unions, and large nonprofit advocacy organizations. Self-organization and mutual aid become the only viable options when political forces ignore or manipulate the very crises they were meant to address. In times of crisis, Tomba contends, “insurgent universality” arises within multiple nodes of sovereignty based in local association. The question always remains, how will the unitary sovereignty in large states react to the alternate nodes of sovereignty that it needed to establish its own power? As Tomba shows, historically the most frequent course of action was to crush these groups, even when the governments called themselves radical—such as the Soviet reaction to the Kronstadt rebellion. Although no violence was involved, Obama's dismantling of the alternative political force that he needed for his election was simply a further iteration of this historical trend.

But Mamdani and the movement that thrust him into power could take another course. The decentralized nature of the groups providing the volunteer force behind the campaign make them difficult for Mamdani himself to dismantle—not that this course of action seems to be his intention. Their independence will most likely not only remain intact, but grow in strength due to this victory—as has happened with the NY DSA. Tensions between the Mamdani administration and these groups will most likely occur, but they will pale in comparison to the tensions that will arise between the administration and the federal and state governments. If he chooses, Mamdani could continue to work with the movement that was so instrumental to his election to confront the larger forces that will surely attempt to thwart his agenda. This might result in NYC taking on the characteristics of what David Harvey would call a “rebel city:”[6] a city which takes on an oppositional stance to traditional state sovereignty and the neoliberalism that constitutes the core of so many leaders of these states' policy agendas. This would require a realistic assessment of what Mamdani can and cannot win from the New York State and the Federal government—and an acknowledgment that what the city cannot win from the larger state, it must take care of itself. To maintain the movement, Mamdani must acknowledge the potential for it to constitute itself as a concurrent sovereignty to his own administration, and even cultivate that sovereignty. The Mamdani administration can do this by both not attempting to completely assimilate the groups and individuals that constitute them, and even by giving them unconstrained resources that could allow them to grow as independent entities. Participatory budgeting provides an excellent example of how to recognize and support insurgent sovereignty: wards or neighborhoods are given public funds that they themselves determine how to use; local sovereignty is not only acknowledged but cultivated by larger municipalities. Mamdani seems to recognize the promise of this phenomenon, so there is a chance that he will take steps that could lead to New York acting as a “rebel city,” as Harvey imagines. But even if he does not consciously make these moves, he will not be able to easily contain the insurgent universality that was so fundamental to his victory. Cities that are either directly robbed of their autonomy by larger political entities, abandoned by the trends of international capital, or occupied by police and military forces under the aegis of immigration enforcement will form their own local, independent forms of mutual aid and resistance. Thus, no matter what happens with Mamdani, one should expect to see more examples of “insurgent” sovereignty and more attempts to establish “rebel cities” by networked, grass roots movements. The question remains of how the leaders of these cities will react to the forces autonomously forming in their own backyards, and whether they will embrace them or reject them.

Jason Kosnoskii is a Professor of Political Science atUniversity of Michigan—Flint.

[1] https://theconnector.substack.com/p/solidarity-tech-the-platform-powering?ref=thefarce.org

[2]https://newrepublic.com/article/140245/obamas-lost-army-inside-fall-grassroots-machine

[3]https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/the-kitchen-tables-behind-mamdanis-kitchen-table-strategy/

[4]https://www.dropsitenews.com/p/zohran-mamdani-democratic-socialists-campaign-new-york-city-dsa

[5]Oxford University Press, 2019

[6]Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. London: Verso 2012.