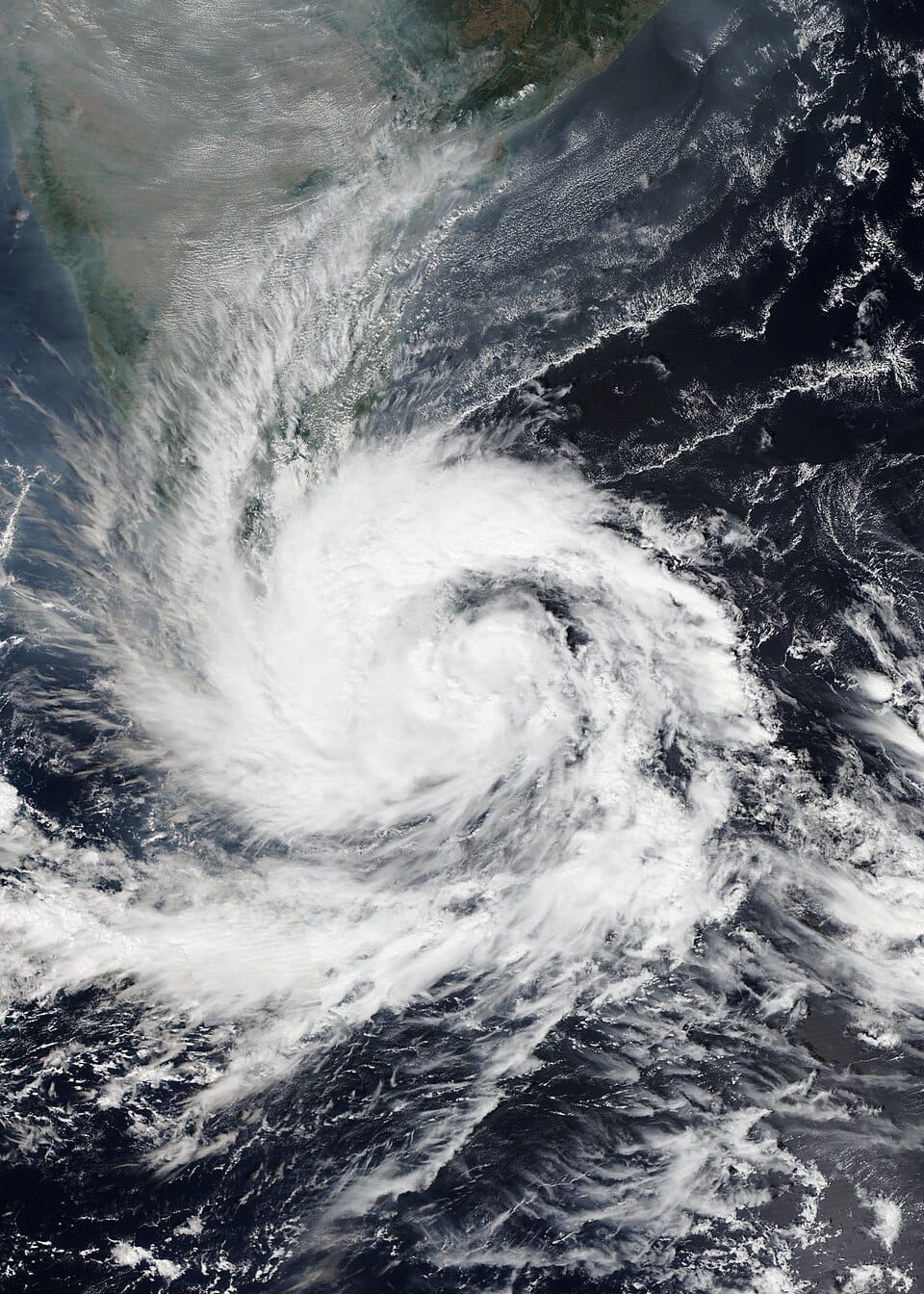

Sri Lanka and its people are not new to natural hazards. Droughts, floods, landslides, epidemics and many other hazards are standard features of the recent history of the Island. The current predicament of the country due to Cyclone Ditwah, which unleashed catastrophic flooding and landslides, is the latest disaster people are experiencing.

Among many scholars and policymakers, it is generally accepted that there are no natural disasters. As human beings, we tend to call a natural hazard a disaster when it affects our social, political, cultural, economic and environmental structures. While there are natural hazards, disasters are not natural. In every phase of a hazard – causes, preparedness and risk reduction, results and responses, vulnerabilities, recovery and reconstruction – people experience impacts shaped by their socioeconomic conditions. The effects of Cyclone Ditwah provide the most staggering confirmation of this axiom. This is not just an academic perspective; it is a practical one. This has everything to do with how societies prepare for and respond to natural hazards, and how they recover and rebuild afterwards. It is challenging, and it is too early on the heels of such an unnecessarily devastating disaster; however, it is essential to examine the social, cultural, economic, political, and environmental aspects of disaster response.

Communities as First Responders

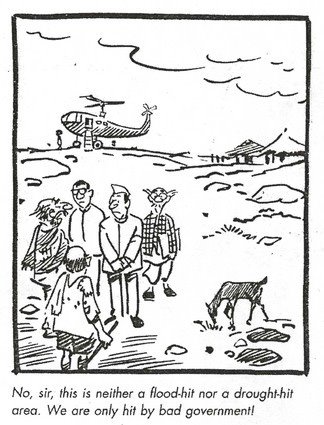

As explained by R. K. Laxman (1921 – 2015), a prominent Indian cartoonist, illustrator, and humorist, natural disasters are caused by poor governance.

Sri Lanka has one of the most comprehensive disaster management acts, which the United Nations commended at the time. The Disaster Management Act, 2005 (Act No. 13 of 2005), which aims to protect human life and the environment of Sri Lanka from the consequences of natural hazards by preparing national policies and plans and by appointing centrally coordinated committees and institutions to give effect to such policies and plans.[1] This Act provides for the establishment of the National Council for Disaster Management and the Disaster Management Centre, the appointment of Technical Advisory Committees, the preparation of disaster management plans, the declaration of a state of disaster, and many other activities related to disaster preparedness, response, and recovery. Any policy or legislation is effective based on leadership and the people who implement it.

Despite all these policy measures, Sri Lanka is experiencing one of its worst flood disasters in two decades, with nearly one million people affected and more than 400 reported dead or missing.[2] The United Nations further reports that thousands of homes are destroyed across the country with severe disruption to electricity, mobile and communications, and transport networks, especially in northern districts. According to the UN Flash Update No. 2, the already fragile healthcare system in Sri Lanka is under strain. Following floods, the risk of infectious diseases increases, posing a challenge in the coming months. As most farmlands are affected, there might be a food shortage. The country is on the brink of a series of disasters to come.

Despite the poor governance, people in Sri Lanka have once again shown how capable they are of helping each other in times of disaster. Immediately, community groups, Buddhist and Hindu temples, mosques, churches, restaurants, and ordinary citizens came together to establish community kitchens, deliver supplies, and reach out to those cut off from water.[3] During the 2004 tsunami, there were similar community responses that primarily cared for affected populations. This confirmed again that affected populations themselves are the first responders to disasters and faster than any government or organised disaster response.[4]

Beyond the Disaster: Thinking Recovery, Rebuilding and Development

Although devastating as it is, the tragedy of Sri Lanka is neither unique nor unexpected. The next obvious phase is recovery, rebuilding, and development. The President of Sri Lanka is already talking about building a better nation than the one that existed before.[5] Politicians and political leaders always say that in the aftermath of crises. The responsibility lies with the Sri Lankan President to ensure that this is not just political rhetoric.

Disasters are not natural, and there are dimensions of exclusion and discrimination in recovery, rebuilding, and development that follow a long history of similar experiences. The 1976 Guatemalan earthquake, which displaced over 1.5 million people and killed about 23,000 people, was called a “class quake” by a young human geographer who visited Guatemala City at that time.[6] The most affected by the earthquake were the poor and despondent in the Central American nation, not the wealthy. After the 2004 tsunami in Sri Lanka, the local fishing communities were told not to rebuild their houses in the coastal belt. This “recovery and rebuilding” process forcibly prevented them from their livelihoods; however, it secured the coast for wealthy tourists. Fishing communities in Sri Lanka famously called this a “second tsunami”. Similarly, after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, communities in New Orleans were murmuring about Katrina as “Hurricane Bush”, mainly because the recovery, rebuilding and development efforts excluded certain races, ethnic groups, and social classes.[7]

At all phases, including recovery and rebuilding, disasters do not simply flatten landscapes, washing them smooth, and creating new and better opportunities for development. Rather, they destabilise the foundations of social, political, cultural, economic, and environmental structures they encounter. Sri Lanka is already divided by politics, religion, ethnicity, and class. A recovery, rebuilding, and development process needs to consider bridging these divisions and facilitating inclusion among the population. It is also important to remember that Sri Lanka is subject to severe climate change impacts. While climatic events may be a great equaliser (we are all in the same boat), they also magnify existing discriminations and exclusions. Given uneven development since 1948, including the continuation of colonial administrative structures alongside neoliberal economic development policies, this may be an opportunity for Sri Lanka and its people to transform the country. This requires establishing a dialogue on Sri Lanka-owned development that includes the real development specialist.

People themselves are the experts of their lives. They know intimately what they need. Sri Lanka may not need "development" like in China, Europe, or North America. There is a need for "development" that is suitable for Sri Lankan people and their social, political, cultural, economic, and environmental realities. The real experts are not coming from academia or abroad. The real experts are the Sri Lankans themselves – living in Sri Lanka. Despite the disasters and conflicts they have experienced for generations, they have developed sophisticated yet pragmatic approaches to crisis management. These approaches are based on lived experiences, time-tested mechanisms, and realistic strategies. The Government of Sri Lanka has the opportunity to incorporate diverse views and knowledge.

In the end, the question of recovery, rebuilding and development is not technical and neutral. It is political, social, cultural, economic, and environmental. The Government of Sri Lanka cannot abandon these realities in the face of such a widespread disaster. Sri Lanka needs a leadership that can unite and empower the population. Given the chaotic response to unnecessary deaths, displacement and destruction, any attempt to impose top-down and opaque solutions without the people's active participation is likely to create further burden on the already suffering population. Natural disasters do not exist; the solutions to the chaotic situations the country is facing lie within the Sri Lankan people.

[1]Parliament of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, (2005), The Sri Lanka Disaster Management Act, No. 13 of 2005, Published as a Supplement to Part II of the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka of May 13, 2005.

[2]United Nations, (2025), Cyclone Ditwah brings worst flooding in decades to Sri Lanka, killing hundreds, Available at: https://news.un.org/en/story/2025/11/1166474

[3]News Wire, (20250, Volunteer operations underway to support disaster affected families ns, Available at: https://www.newswire.lk/2025/11/30/volunteer-operations-underway-to-support-disaster-affected-families/

[4]O’Keefe, P., O’Brien, G., Jayawickrama, J., (2015), Disastrous Disasters: A Polemic on Capitalism, Climate Change and Humanitarianism, In Collins, A., Jones, S., Manyena, S.B., Jayawickrama, J., (eds), Natural Hazards, Risks, and Disasters in Society: A Cross-Disciplinary Overview, Elsevier’s Hazards and Disasters Series, Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 34-43.

[5]News Wire, (2025), Full Speech: President's Address to the Nation, Available at: https://www.newsfirst.lk/2025/12/01/full-speech-president-s-address-to-the-nation

[6]O’Keefe, Phil, Westgate, K., and Wisner, B., (1976), Taking the Naturalness out of Natural Disasters, Nature, vol. 260.

[7]Smith, N., (2006), There’s no such thing as a natural disaster, Understanding Katrina: perspectives from the social sciences, 11.

Janaka Jayawickrama is Professor of Social Anthropology and Director of the Research Centre for Health and Wellbeing at Shanghai University, China. Trained in India, the USA, and UK, Janaka has been collaborating with disaster, conflict, and uneven development affected communities in Asia, Africa, and West Asia (or Middle East) since 1994. He continues to work in Sri Lanka in collaboration with universities and community groups on disaster risk reduction, development, and climate change. Janaka holds many honorary positions with universities in the UK, Sweden, China, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka.