The immediate answer to this question is no. Cultural transit, translation and transformation are sustained in networks historically constructed in asymmetrical relations of power. Despite the illusions of liberal humanists, the exchange is never equal. Even the currency is rarely common. Presenting as a universal template the philosopher exchanging views in the coffee house, seeking a consensual understanding of the world, is an Occidental conceit. Yet, if we consider the idea of the transcultural more closely, we can perhaps discover an analytical cutting edge that allows us to move elsewhere and shift position. For, what do we mean by transcultural? Most obviously, it suggests the establishment of an in-between space that is irreducible to presumed points of departure and arrival, as though it were a simple movement back and forth from my culture and history to another. If it is a movement that involves unequal relations of power it can never be neutral. If it tends initially to operate for the benefit of the instigator of the movement, the philosopher sipping the ‘Muslim drink’ (coffee) in the tranquillity of the public sphere, more slyly and significantly, the assumed origin and destination of the passage are clearly contaminated by the transit and translation. This is what Homi Bhabha famously referred to as the production of a third space. Fixed premises and settled procedures fall away to be replaced by transitory encounters emerging from historical processes and agonistic practices. The presumed security of stable identities is undone, challenged by an altogether more open and less guaranteed manner of belonging.[1]

The undoing of earlier securities, personal and political, intellectual and disciplinary, has undoubtedly characterised the last sixty odd years in the Occident but it is not simply the outcome of a self-induced ‘crisis’. Of course, youth rebellion and music, feminism, gender politics, cheap travel and drugs are important. But in a crucial, although always disproportionate, counter-point, race, racism, anti-colonial resistance and the revolts, announcing other worlds and an impossible domestication, crack the mirror and spill the coffee. Such a change in the axes clearly impacts on how we understand what constitutes critical knowledge and their associated disciplinary practices. For these, too, are sustained in the creolising procedures of a historical constellation. The usual insistence on atemporal ‘scientific’ protocols, permitting their separation – so-called ‘critical distance’ – from the historical processes that authorise them, ultimately betrays arbitrary closure and epistemic violence. Prospects sustained by cultural and postcolonial studies, de-colonial and transcultural thinking, are clearly seeking to expose and exceed such limits.

So much has been, and will be, discussed and written on this rift, this tear in the fabric of contemporary thought; what an Algerian-born Marxist famously called an ‘epistemological rupture’, and another Algerian philosopher proposed as a necessary deconstruction. But, for the moment, let us not run too fast with Louis Althusser and Jacques Derrida. For this critique of the knowledge apparatus is by no means hegemonic or widely welcomed. It is deeply resisted in the inertia of academic habits and accompanying professional hostility; that is, in the disciplines whose role is to reproduce the order of discourse, and to discipline us, both intellectually and institutionally. So, an approach that deliberately muddies the water, disbands the premises and contaminates the language will be forcibly resisted, even if we might choose to welcome it as signs of change. For it poses the opportunity to refuse to reproduce the status quo and insist on the challenge and vulnerabilities of critical thinking. Right now, under the impact of an increasingly brutal swerve into the right-wing lexicon of authoritarian politics and the neo-liberal management of education responding almost exclusively to capital, that horizon has increasingly narrowed. The cuts, both economical and ideological, leaves the liberal body bleeding. It now either toughens up and adopts a business-like language to navigate the rigid metaphysics of the market, or retreats to rant against the increasing leaden skies of an illiberal world. It often simply embraces a complicit silence.

So, rather than diagnosing the cruel retreat of critical thinking into the folds of capitalism and adopting a wearied realism, I wish to propose a small exercise that might suggest other ways to inhabit our languages and institutions.

I will commence from the Oriental Institute in Naples (today the University of Naples, Orientale), where I taught for many years, but whose detailed history largely remains a mystery. On the institute’s website, after recounting its foundation as a religious mission in the Eighteenth century, the history then jumps from 1888, when it was transformed into the Royal College of Asian Studies, to the present. Silence hangs over the intervening years; that is, over its modern articulation as fundamentally a colonial enterprise, first in a liberal, then a fascist, regime. But let us go back.

Born in 1732, with the intent of spreading Catholicism in China, the Orientale was most certainly part of the Enlightenment drive to render the rest of the world transparent to material and metaphysical accumulation. As the first institute of Oriental studies in the West, it occupies a place in Edward Said’s mapping of ‘Orientalism’ as an essential component of the biography of the Occident and the making of present-day Italy. The study and appropriation of the other was central to the centrality of colonialism in the building of the modern nation state everywhere in Europe. In Italy, from the 1880s onwards, this would explicitly require the future education of colonial administrators for the Italian Empire. In 1904, a new section of the Neapolitan institute was proposed to teach colonial geography, the modern history of colonisation, colonial law, the history and culture of Islam, the science of hygiene and ethnology. The declared purpose was to provide ‘a complete and practical knowledge of the Italian colonies and their connected problems’ in order ‘to promote their intelligent and fruitful use’.[2] To be modern was to be colonial in intent and imperial in practice. Every state in Europe practised this logic.

In the Relazione sull’Insegnamento Coloniale Italiano by Lodovico Nocentini, published in 1905 by the Istituto Coloniale Internazionale – that in 1922 becomes the Fascist Colonial Institute, and then in 1995, the Italian Institute for Africa and the Orient (IsIAO) under the presidency of Gherardo Gnoli, ex-Rector of the Orientale of Naples – the projected colonial formation and required pedagogy is clearly set out.[3] The report initiates with a discussion of Italian schools abroad. Italian as a pedagogic exercise in ‘patriotic sentiments’ and the school as the symbol of ‘national unity’ is continually reiterated. The very term ‘colonial’ here has a double valency, pointing both to Italian communities abroad as ‘colonies’, in the sense of outposts of the nation, alongside the more obvious administration of the territories seized by Italy in Africa.

Apart from reporting on Italian schools abroad, the Colonial Diplomatic School at the University of Rome, the Royal International Institute in Turin and the Italian-Greek College in Calabria (a heritage of the Albanese communities who had fled the Ottomans), over a quarter of the report is dedicated to the Regio Istituto Orientale in Napoli. The section on the Orientale begins: ‘The Oriental Institute in Naples is the oldest school of oriental languages in Europe and originally had a truly colonial character. In 1707, the Jesuit Matteo Ripa from Eboli left Rome for China...’.[4] The relative failure of the missionary project led after the unification of Italy to the ‘Chinese College’ being converted into the Asiatic College and redirected towards the teaching of languages (Chinese, Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Indonesian, Japanese, Slav, Serb and modern Greek) for Legation and Consular personnel. This was further refined in 1880 by government decree and led eventually to three areas of teaching: International Private Law, Colonial and commercial economy and the History of Trade, Diplomacy and Treaties. What clearly emerges, as throughout Europe at the time, is the intersection between colonialism, capitalist enterprise and national identity.

In recent scholarly research on the colonial constitution of modernity the Orientale has been explicitly referenced. On the detailed history of the teaching of colonial studies in Italy up until the Second World War, including the tussles under Fascism between Rome and Naples (the ‘bridgehead to the colonies), Valeria Deplano has written a fascinating study.[5] In 1929, the Italian Africa Society (Società Africana Italiana or SAI founded in Naples in 1882, itself a transformation from the Club Africano di Napoli of 1880) proposed that the Orientale be transformed into a Colonial University. This was blocked by the law of that period forbidding the creation of new universities. In the subsequent debates on the plausibility of this prospect, the Orientale was persistently considered central to the proposed articulation of a colonial education and formation.[6] By the 1930s the institution was deeply engaged, in symbiosis with the SAI, in providing a colonial education, both linguistically and in the administrative and social sciences. This was motivated by considerations of the importance of North Africa as a Mediterranean component in the millenarian confrontation between Occident and Orient.[7] By the end of the decade, the Orientale had inaugurated a degree course in ‘colonial sciences’.

More recently, Floriana Galluccio and Eleonora Guadagno, and partially building on the earlier work of the historians Alessandro Triulzi and Silvana Palma (all from the Orientale), have returned to this archive.[8] They have noted the difficulties in exploring the material deposited at the Orientale owing to its fragmentation, lack of organisation and its not being available to public access. They, too, extract from this archive the intrinsic relationship between geographical concerns and Italian colonialism under the rubric of ‘exploring Africa’, noting that the history of the Orientale ‘between the XIX and XX centuries is tightly linked to colonial matters’.[9]

The very loaded discussion of appropriating and profiting from the unilateral appropriation of other people’s territories, histories, cultures and lives – in Italy’s case mainly in East and North Africa – is generally discussed institutionally in the seemingly neutral terms of juridical, economic and political administration. The barely disguised positivism of these ‘sciences’ as then practised (in some cases still are) wraps the essential violence of nation building through colonial violence in the bland language of everyday administration. Alongside the immediate horrors of military warfare in Eritrea, Somalia, Ethiopia and Libya – not always to European benefit as the Italians discovered in 1896 at Adua in Ethiopia and the British at Khartoum in 1885 – there was the altogether deeper and far lengthy cut of epistemological violence that continues to reach across the decades into the present. The indigenous, the natives, the ‘Arabs’ and the ‘Muslims’ are nameless and voiceless. The narration is not for them. At the most, they represent collateral damage in the story of Occidental ‘progress’. Which, today, echoes most forcibly in the West’s continuing (non)narration of the genocide in Gaza. The Palestinians apparently have no history, except for their ‘terroristic’ inception on October 7, 2023.

Contemporary concerns always offer keys to reopen the archives. Listened to again they invariably contest the narrative that seeks confirmation of its authority in the status quo. History is an altogether messier and more unstable affair. It does not simply pass, nor do its interrogations peacefully lie down to rest between the lines of a ‘scientific’ text. So, how are we to consider the supposedly neutral languages of International Relations and Political Science, along with the intrinsic entanglement of Geography and colonialism, in the historical impossibility of separating them from this matrix. If there is still a critical history of the institute to be written, we could nevertheless commence with some of its scattered remains.

This might involve adding to the above contemporary essays and the Report of 1905, further evidence from the two museums at the Orientale. Located in the basement of the Rectorate, to the casual visitor they seem largely unreflective of their exhibition logic or explanatory power, neutered by ‘scientificity’,[10] I imagine. Again, the material is very fragmentary. One is dedicated to the archaeologist Umberto Scerrato, who founded and taught Oriental Archaeology at the Orientale in the 1960s. It contains interesting thirteenth-century Islamic ceramic fragments from an archaeological dig conducted by Scerrato in 1956 at Ghazni in Afghanistan. This city, once part of the empire of Alexander the Great, was capital of the Ghaznavid Empire (instrumental in taking Islam to India), and is close to the nearby site of two famous minaret towers from the late eleventh and early twelfth century, composed of intricate brickwork and subtle geometric patterns and Kufic inscriptions from the Quran (the upper part of the towers collapsed in an earthquake in 1902). The city was destroyed around 1220 by Ögedei Khan, the third son of Genghis Khan. A century later, the Moroccan geographer Ibn Battuta confirmed that the city was still in ruins. What remained of Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi’s eleventh-century tomb outside the city was carefully described by Robert Bryon in 1934 in The Road to Oxiana. He acidly noted that the famously decorated massive wooden doors of the funerary chamber had been looted by the British Army in the First Afghan War (1839-42) and carried off to India on the false assumption that they were the portals of the Hindu temple of Somnath in Gujarat that Mahmud Ghaznavi had sacked in 1025-6 in one of his seventeen raids on Punjab. The doors now lie abandoned in dilapidated condition in the Agra Fort. Their description in English concludes that ‘In no way is it related to this fort, or the Mughals, and it is lying here either as a war trophy of the British campaign of 1842, or as a sad reminder of the historic lies of the East India Co.’

The other museum on the same premises is the Museum of the Italian Africa Society, largely composed of ethnographic materials and ‘exotica’ brought back from explorations and commercial undertakings. On the official web site of the Orientale this lengthy colonial period that the Society and Museum points to is completely missing, hidden away in the basement where, between a fire extinguisher and an umbrella stand, lies some of the testimony to its foundations and mission. But the problem is not the make-shift organisation of the objects on display, but rather the narrative, or absence of. Behind the seeming neutrality of the clipped descriptions lies an altogether more complex web of coloniality and knowledge formation impacting the present.

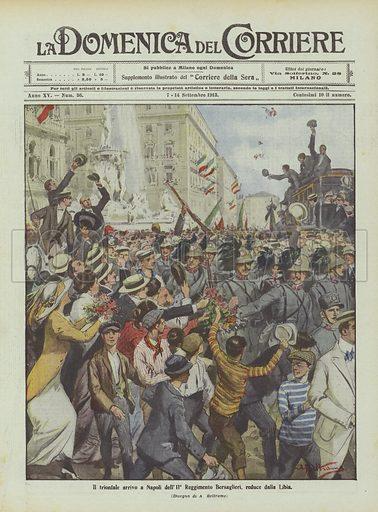

The fragmentary nature serves to remind us that the archive is always incomplete. It resists closure, and so it continues to interrogate us. It can even be unlocked by a single object, such as the cover of the La Domenica del Corriere in September 1913, portraying the ‘triumphal arrival in Naples’ of the Bersaglieri after the Italian seizure of Ottoman Libya.

The archive is, also and always, a site of interpretation. It is constructed from the materials available. These never present themselves raw and nude, but are elaborated and signified by those excavating and seeking to establish an always transitory coherence. So, the definition of both material and archive is never settled. How, why and who constitute its definitions and signification are also part of the archival process and the historical processes in which it is suspended. In stepping beyond the empirical boundaries, and acknowledging the impossibility of ever completing the picture, exhausting the archive and concluding the history, it also involves working with absences, or, better still, treating those absences as part of an analytical net. And the net, as the Italian philosopher Gianni Vattimo once pointed out, is also full of holes. While it captures some things, others escape.

Of course, all of this can simply be considered a matter of minor oddities, colonial debris abandoned in the corner of a modern European university. However, they do hint at a manner of approaching archives that echoes strongly in the unwillingness – at least publicly – to register, work with and perhaps even benefit from acknowledging a colonial history. If the increasing diversification of the present student body at the Orientale, and in Italy in general, speaks to this repressed past, institutions themselves remain decidedly silent. Historically, culturally and intellectually, this should decidedly not involve being blocked by embarrassment, guilt or shame. Rather, it poses the critical challenge of elaborating an uncomfortable and problematic heritage – both its colonial and racist premises are difficult to avoid – that weave together multiple histories and analytical complexities. When yesterday’s ‘objects’ – the histories, cultures and lives of the colonial gaze – justly refuse that state, this enriches both disciplinary specialisations in historical, political and area studies, and the overall shaping of curricula and research across the human and social sciences.

And then, despite the predictability of institutional arrangements, there are always opposing currents at work. In the wake of Cultural Studies emerging in Italy in the field of English language and literature largely at the Orientale in the 1980s and 1990s there emerged a strong commitment to postcolonial studies. After visits by Homi Bhabha and Hanif Kureishi in 1993, the international conference “The Postcolonial Question: Common Skies, Divided Horizons” was organized in Naples that same year.[11] Among those invited to speak were Stuart and Catherine Hall, Paul Gilroy, Vron Ware, Trinh T. Minh-ha, Angela McRobbie, and Lawrence Grossberg, along with some teachers and graduate students from the Orientale. Other colleagues from the institute’s Oriental Studies department were also invited. No one showed up. The “anti-scientific” suspect Edward Said was then considered anathema, and postcolonial studies simply an ideological smokescreen obscuring real research. Only in recent years, with a younger generation of scholars working on the history and sociology of West Asia and North Africa, has the situation changed significantly. This has also been accompanied by a development of decolonial studies in the fields of sociology and anthropology at the same institute. Such initiatives have obviously had a profound impact on the courses taught at the Orientale, involving thousands of students at various degree levels.

The de-colonial insistence lies in the unpacking of history, its conceptual regime, political practices and intellectual coordinates. A contemporary example that rescues scholarly labour from the accusation of merely reproducing a bullying status quo is the careful research conducted on the imbrication of the University of Edinburgh under the Chancellorship of Lord Arthur Balfour, he of the 1917 Declaration, in promoting the Zionist project in Palestine. This research forms part of an extensive and nuanced survey – Decolonised Transformations: Confronting the University of Edinburgh’s History and Legacies of Enslavement and Colonialism (published by the university, June 2025). The declared aim of the Report is ‘to shine light on some of the darker aspects of the University’s history, including those that were taking place at the very time that it was developing itself as a centre of Enlightenment thinking.’[12] As part of the Report ‘addressing and repairing imperial legacies’ (16) is the more than 100 page Appendix 3 on Palestine prepared by Nicola Perugini and Shaira Vadasaria.[13] This Appendix brings together the brutal intricacies forged in the matrix of eugenics, colonialism and antisemitism that dispatched the ‘Jewish Question’ to the Middle East, while blithely ignoring the rights of the indigenous Palestinian population. It betrays the full assembly of racial thinking behind modern empire – both towards the Ashkenazim fleeing pogroms in eastern Europe and being denied refuge in Britain (again the antisemitic Balfour, this time as Prime Minister with the 1905 Alien Act) and towards the Arabs for being an ‘inferior race’ subjugated to imperial rule.

Borrowing from part of the title of the second section of the Appendix, this brings us to confronting the ‘past as present’. We are digging into the archives, both those of the Orientale of Naples, the University of Edinburgh and, given their extensive intersection with the question, those that Israel and the West seek schematically to destroy through obliterating Palestinian history and rights. In all of this lies the attempted extermination of the memories of the indigenous and the Occidental white-washing of its colonial archives and memories. Most obviously, this means imperial Britain and its fundamental role in creating the conditions that have led to what Rashid Khalidi calls the Hundred Year War against the Palestinians.[14] And this leads directly into the present genocide that engulfs all of us in the West. Political responsibility and critical reparation are not separate from intellectual and cultural complicity. The discursive regimes that pursue their research under the blanket of scholarly premises, neutrality and scientific protocols are also, to use Michael Rothberg’s concept, implicated in this formation of power and knowledge.[15] Given the failure of the Western knowledge apparatus in the face of Gaza, this means adopting another compass, another grammar, with which to construct a sense of the present and possible futures.[16]

And then we come back to the initial question: can we decolonise ourselves, our institutions, our language? Before the global atrocity exhibition that is Gaza, I think that the answer remains a resounding no. Petrified by the apocalypse of Occidental ‘values’ literally going up in smoke we are apparently at a loss for words and are unable to reach beyond the political platitudes of Palestinian ‘terrorism’ and Israel's ‘right to defend itself’. Our language has been occupied and cruelly contorted: it is the colonised who has the right to defend itself, and the coloniser who invariably deploys terror to maintain its regime. Any viewing of Gillo Pontecorvo’s brilliant film Battle of Algiers (1966) both explains this and equips us with a language more susceptible to histories that do not automatically respect our will. Just to ask two very simple questions before the present holocaust destroys our narrative and scorches our grip on the world. Do the Palestinians have the right to have rights? And why must they bear the burden of centuries of European antisemitism culminating in the Shoah? Not only do I hear no answers, I do not even hear the questions. So, after all, it seems that Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth (1961) was right. It is perhaps time to abandon that Europe which insists on its humanism and universal values while continuing to slaughter peoples in every corner of the planet.

Iain Chambers studied at the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at Birmingham University before moving to Naples, where he taught Cultural, Postcolonial and Mediterranean Studies at the University of Naples, L’Orientale. He is presently an independent researcher and writes regularly for the Italian daily il Manifesto. Among his publications are Migrancy, Culture, Identity (1994), Mediterranean Crossings (2008), Postcolonial Interruptions, Unauthorised Modernities (2017), and with Marta Cariello, The Mediterranean Question (2025). With Lidia Curti, he edited the volume The Postcolonial Question. Common Skies, Divided Horizons (1995). In 2022, he participated in documenta fifteen as a member of the collective «Jimmie Durham & A Stick in the Forest by the Side of the Road»

[1]In preparing this piece I would like to acknowledge the beautiful and informed web site of Giulia Gallini – The Road to Oxiana Project: https://squarekufic.com/the-road-to-oxiana-project/

[2]Uoldelul Chelati Dirar: https://www.africarivista.it/sulle-tracce-dellistituto-universitario-orientale-di-napoli/267261/

[3]The institute was closed in 2012, and its books, manuscripts and maps transferred to the National Library in Rome.

[4]Ludovico Nocentini, Relazione sull’Insegnamento Coloniale Italiano, Casa Editrice Italiana, Roma,1905, p.10.

[5]Valeria Deplano, ‘Educare oltremare. La Società Africana e il colonialismo fascista’, Riviste della Storia dell’Europa Mediterranea, numero 9, dicembre 2012.

[6] Deplano, op.cit, pp.99-100.

[7]Deplano, op.cit, p.104.

[8]Floriana Galluccio and Eleonora Guadagno, ‘Il limes coloniale italiano e il ruolo (inesplorato) del Club Africano di Napoli. Nuovi cantieri di ricerca: per una lettura decoloniale in archivio’, Semestrale di Studi e Ricerche di Geografia, XXXVI, 2, 2024.

[9]Galluccio e Guadagno, op. cit., p.114.

[10] http://museorientale.unior.it/

[11]Iain Chambers and Lidia Curti, The Postcolonial Question. Common skies, divided horizons, Routledge, London, 1996.

[12]The Report is available here: https://www.ed.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2025-07/Decolonised Transformations: Confronting the University of Edinburgh’s History and Legacies of Enslavement and Colonialism.pdf, p.5

[13]Appendix 3: University of Edinburgh and the Question of Palestine: Balfour’s Imperial Legacy and Afterlife:

[14]Rashid Khalidi, The Hundred Years War on Palestine. A History of Settler Colonial Conquest and Resistance, Profile Books, London 2020.

[15]Michael Rothberg, The Implicated Subject, Stanford University Press, Stanford, 2019.

[16] The image of Germany, Britain and France surveying the present genocide in Gaza is by Andrew Gilbert. By gentle concession of the artist.