Luca Guadagnino’s After the Hunt begins like a film searching for truth. It speaks softly about consent, power, and doubt, but what it uncovers is something older and harder to name: how institutions protect themselves by calling it reflection. Beneath the polished dialogue and candlelit rooms is a quiet instinct for survival. Guilt is shown, but never shared. The appearance of thought replaces the work of justice. Maggie, the Black woman at the story’s centre, is not silenced by accident; she is folded into a tale that needs her pain but cannot bear her power.

The Set-Up: A Story Built on Uneven Ground

The story begins at Yale, where Alma (Julia Roberts), a philosophy professor, hosts a faculty party that radiates comfort and hierarchy. Her students are there to flatter, her peers to impress. Among the guests are Hank (Andrew Garfield), a close friend and fellow professor, and Maggie (Ayo Edebiri), Alma’s PhD student. The next morning, Maggie appears outside Alma’s apartment, trembling, saying Hank walked her home and “crossed a line.”

That phrase defines the film’s ethical experiment. Guadagnino refuses to show what happened. The accusation breaks the calm, but Guadagnino withholds clarity. Hank denies it. Alma hesitates. The film builds its tension on not knowing. Ambiguity becomes method, not meaning.

Power Disguised as Doubt

Guadagnino has said he wants the audience to “find their own footing.” But neutrality is not neutral when power is uneven. Alma is tenured, Hank is protected by friendship and prestige, and Maggie is both a student and a Black woman in a white elite space. To treat them as equals is to erase history itself.

Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality helps explain what the film refuses to see. Power is not singular. It compounds through race, gender, class, and institutional status. Maggie stands at that intersection, where visibility and disbelief collide. By flattening these realities into a shared moral puzzle, the film turns systemic inequality into a philosophical exercise. Evasion here protects the powerful.

Alma’s Confession and the Shift of Sympathy

Midway through, Alma tells her husband that as a teenager, she once lied about being assaulted, and the man later took his life. The film pivots around this revelation. What began as Maggie’s trauma becomes Alma’s guilt. Her remorse takes centre stage. Her confession becomes a metaphor, suggesting that truth is fluid and accusations are dangerous.

This is where Crenshaw’s insight becomes crucial. Institutions confronted with harm often redirect attention from the victim’s experience to the crisis of character of those accused. After the Hunt does the same. Maggie’s accusation opens the story, but Alma’s conscience ends it.

Consent Repeated, Yet Ignored

Later, in a private encounter, Hank forces himself on Alma. She tells him to stop. He does not listen. She pushes him away. The scene mirrors Maggie’s story almost exactly. The truth is visible now, yet the film treats it as Alma’s turning point rather than Maggie’s vindication. Even when the pattern is undeniable, the story protects its focus on white introspection. The violence becomes a lesson for Alma instead of justice for Maggie.

Collapse and Reinvention

By the final act, the fallout is complete. Alma is suspended after being caught using a colleague's prescription pad. Hank disappears. Maggie, alienated and furious, slaps Alma during a confrontation and walks away. Then time jumps. Five years later, Alma is dean of Yale. Hank has rebranded himself as a political strategist. Maggie reappears for a single meeting in a restaurant.

Their conversation in the café is polite but drained of emotion. Maggie says she has given up on retribution a long time ago. She appears content, engaged to a woman, but professionally undefined. The final scene shows a twenty-dollar bill left on the table. Guadagnino’s voice says, “cut.” It is meant as a clever reminder that truth is constructed. In reality, it reveals who still decides what truth looks like.

Intersectionality Ignored

Crenshaw’s framework was never about identity categories. It was about how structures of power interact. After the Hunt acknowledges Maggie’s race, gender, class, and sexuality, yet refuses to connect them. Her Blackness is visible but irrelevant to the script. Her queerness is mentioned once. Her student status remains the easiest reason to doubt her.

The result is a story that recognises difference without consequence. Maggie’s experience of power inside a white academic institution should be central. Instead, it becomes background for Alma’s redemption. The Black woman animates the film’s crisis of conscience, then vanishes when reflection turns uncomfortable.

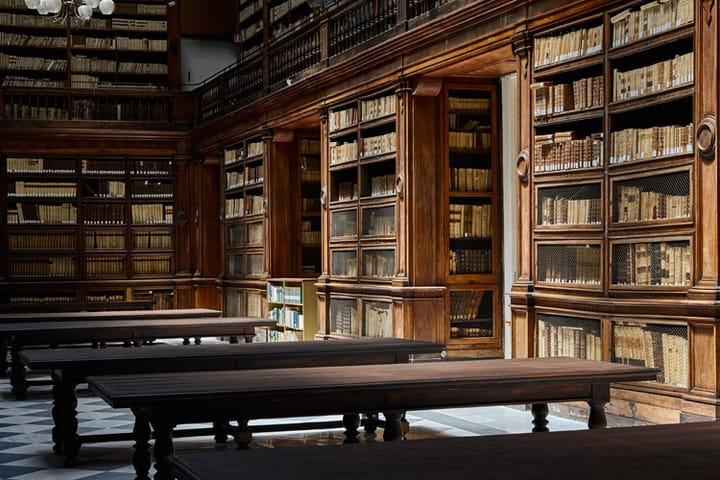

The Aesthetic of Detachment

Guadagnino frames this world of an elite university with surgical precision. Every corridor glows. Every table setting looks curated. The camera never leaves the comfort of the elite bubble it studies. Its stillness is institutional, beauty staged to smother the wound. Yale, like Guadagnino’s lens, disguises violence as civility. The tone is too polished for rage.

By the end, the hierarchy is intact. Alma, who doubted her student, is rewarded with a promotion. Hank, accused of assault, thrives elsewhere. Maggie, who told the truth, walks out of frame. The film calls this maturity. Crenshaw would call it exhaustion.

Systems of power rarely collapse under scrutiny. They perform contrition, issue statements, hold inquiries, and continue unchanged. Exposure becomes ceremony. Accountability becomes theatre. The machine learns to display its own inspection as evidence of progress. After the Hunt ends with calm, not because justice is served, but because order has been restored.

What the Film Refuses to See

The film nods toward #MeToo and Black Lives Matter but cannot sustain the gaze. It imitates awareness without risk, turning accountability into posture. Maggie’s story becomes a site of avoidance. Her voice is softened, her pain filtered through questions of class and reputation. By pointing to her wealth and alleged plagiarism, the film redirects suspicion onto her, allowing privilege to masquerade as fairness. What we are left with is not complexity, but hesitation, a refusal to confront what rectitude would actually require. It gives her status but denies her power. Maggie’s existence fuels Alma’s self-realisation. The Black woman’s pain becomes a mirror for white enlightenment. The system that protects Alma and Hank survives because it can turn every accusation into a lesson in civility.

After the Hunt

Guadagnino said he wanted to make a film about “moral ruins.” What he has made is a film about restoration. The ruins belong to the marginalised; the improvement belongs to those already in power. Alma and Hank fall briefly, then rise higher.

The question “Did Hank do it?” never receives an answer, but the outcome speaks for itself. The powerful recover. The institution continues. The woman who spoke up walks away.

After the Hunt wants to explore the complexity of truth, but its real subject is the comfort of entitlement. It asks us to debate what happened instead of asking who benefits from our uncertainty.

Dr. Abdullah Yusuf is a Senior Lecturer (Associate Professor) in Politics and International Relations at the University of Dundee, UK. He studied Public Policy and Diplomacy at The Australian National University in Canberra, Australia, and holds a PhD in International Relations from the University of Dundee. His research and scholarship interests include: International organizations (United Nations, League of Arab States, and African Union); Politics of the Middle East, including Palestine, Israel, and the Arab-Israeli conflict; Politics of humanitarian armed interventions; Peacekeeping and post-conflict peacebuilding; International law and refugee protection; Climate politics; Post-colonial Studies. For more details on my teaching, research, and scholarship profile, please visit: his research profile and bio.