Many of the changes that explain today's world order took place in the nineteen nineties. With the collapse of the Union of Socialist Soviet Republics (USSR) in 1989 and the disintegration of the Socialist bloc, free market economic policies became widespread, provoking the response of anti-globalisation and alter-mondialist movements, both in the global North and in the South of the planet, such as the one launched by the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (Zapatista National Liberation Army, EZLN) on 1 January 1994 in Chiapas, Mexico, the same day on which the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into force. In the European context, the Maastricht Treaty signed in 1992 was extremely complex on account of its two facets: while it called for a federal Europe and established European citizenship, it also ushered in the single currency based on the neo-liberalist economic policies on which the Europeanist project was built. Six years after Spain's accession to the European Union (then the European Communities), considered an epitome of successful entry into modernity, Seville hosted the World’s Fair. The celebrations of the Exposition Universelle in Seville in 1992 reflected an enthusiasm that would eventually lead to the housing bubble that burst in 2008, marking the beginning of the end of the euphoria of globalisation.[1]

On a worldwide scale, the nineties were considered a long decade that began with the fall of the Soviet Union and ended with the war on terror that followed the jihadist attacks of 9/11 in the United States. In Spain, however, the time frame could be extended in both directions. On the one hand, the celebrations of apparatus '92 (Seville hosting Expo '92, Barcelona organising the Olympic Games and Madrid acting as European Cultural Capital), and on the other, the 2003 protests against the Iraq War, rallies that coincided with the transnational activism of the anti-globalisation marches. In the domestic sphere too , demonstrations were mounted against the educational reforms undertaken by the right-wing Partido Popular government and against its poor crisis-management when the Prestige oil tanker sank off the Galician coast, spilling thousands of tonnes of oil and giving rise to the black tide.

For Spain, 1992 represented a turning point in history, a point where international and national narratives converged.The Universal Exhibition, the Olympics, and Madrid’s status as the European cultural capital become – due to their cultural, economic and political dimension – extraordinary[2], multifaceted events which, moreover bring Spain into international debates just as the country is reaching the end of it’s post-transitionperiod. Born of the policies of the fledgling democracy, this series of prestigious events was conceived to celebrate a renewed state project equal to the the changing times but which also located it in a continuum of “modernity” which draws parallels with the modernity of the Discovery of America and of Socialist Spain. In the sphere of art as well, celebrations of multiculturalism and globalisation were emerging and further culminating the narrative of the country's modernisation and its standardisation with European liberal democracies. As observed by Rita Segato, this multiculturalism of the North, promoted by capitalism, doesn't embody a challenge to established order.

History doesn't deal with what takes place but with our story of it. During the years in question, the story of modernity aroused great controversy. Criticism was aimed at the media celebrations organised in 1992 to commemorate the fifth centenary of the discovery of America and at how that spectacularisation of the conquest of America would make it disappear from historical memory. In a short essay entitled 'The Vacuous Quincentenary' published in Third Text review,[3] philosopher Eduardo Subirats reminds us that the celebrations of 1992 concealed the unresolved dilemmas of Spain's colonial past and of the conquest that began in the Iberian peninsula with the deportation on ethnic grounds of Arabs and Jews under the dogma of Catholicism, the first expression of racism, epistemic racism, as observed by authors such as Enrique Dussel[4] in his counter-hegemonic interpretation of the event. Europe didn't only expel or subjugate the Other, but emptied it of social capital by imposing the values and beliefs of its modern project on alternative forms of otherness. From the expulsion of the interior Other to the discovery of the exterior Other, the rationales of domination in the capture of Granada became the models for the conquest and colonisation of America.

In an almost neocolonial display, the Exposition Universelle in Seville emphasised the values of the conquest and domination of America, omitted its scars and silenced the traumas of the past. It acted as an apparatus articulated around an 'appearance of democracy' which hinged on not challenging the complex essentialist colonial structure on which the diplomatic exchange between countries is based. It followed the rationale of those nineteenth-century international shows from which it derived and which acted as propaganda channels for the political regimes they represented, strengthening the leadership of political forces and, at the same time, insisting on the rhetoric of progress and nationalism.

And yet, contrary to the triumphalist and complacent quality of the institutional celebration, some of its agents assumed a critical position. Such was the case of Plus Ultra, the decentralised contemporary art proposal curator Mar Villaespesa and the BNV cultural production company organised for the Andalusia Pavilion at Expo '92. Interventions, eight installations undermining Andalusian monuments to the history of the conquest of America, and the exhibition entitled The Artist and the City, a public art proposal that revised the analytical framework of the concept of site-specificity, were early deviations in those institutions that brought further politicisation of artistic practice in the Spanish state in the early nineties.[5] The same can be said of collaborative and procedural practices, the dissolution of authorship, and the divisions between high culture and popular culture, all of which also objected to the re-emergence of the 'imperialist' unconscious entailed by the commemoration of the discovery of America from the perspective of decolonisation. Strategies of recovery such as centennial commemorations revive narratives, but the lack of critical revision of the past meant that Indian points of view of the celebrations were sidestepped. Indeed, Expo '92 left a number of historical issues related to memory, identity and territory unresolved.

Both inside and outside the country, this “shared” narrative would be widely contested. In Spain, several campaigns against Expo '92 and the Let's Expose '92 platform (that had its own genealogy linked to political activism) were launched in the country by ecologist, feminist and pacifist associations, and included actions and manifestos against the celebration of the centenary, the Europe of Maastricht and globalisation. In Latin America, theoretical reflection focused on making visible the Spanish colonial legacy, although its de-colonial twist triggered a different interpretation of the past that would produce undesired consequences. Indigenous resistance was intensified in the form of assemblies and protest marches (10,000 Indians, among them 6,000 Zapatista supporters, marched in San Cristóbal de las Casas, Mexico, in 1992), social activism campaigns such as 500 Years of Indian Resistance or Black and Popular, and projects like The Conquest group show staged at the Centro Cultural Recoleta in Buenos Aires late in 1991. Liliana Maresca, co-organiser of the latter, presented an installation entitled Equation – El Dorado which explored the myth which connected the mining areas of the West Indies to the lost city of gold generated by the slave trade, out of which was born the primitive accumulation required for the existence of capitalism, or of capitalism as we know it.

Years later, this hypothesis would be deconstructed by the exhibition entitled The Potosí Principle presented at the Museo Reina Sofía in 2010 occasioned by the bicentenary of the independence of American countries. The continent's mines and the viceroyal city of Potosí, cradle of primitive accumulation and of the dynamics of exploitation that would destroy traditional society, are the symbolic and material origin of this connection between modernity, colonialism, the expropriation of workers' rights, slavery and genocide. This world system is based on the political and economic domination of central powers over peripheral powers that began with the perverse cartography that transformed the Atlantic into the geopolitical centre of the colonial world. This was a foundational moment of capitalism and of the Eurocentric ethnic-racial-hetero-patriarchal device that, with pretensions of universality, destroyed the theoretical resources of large peripheral cultures to form a coloniality of power that would have survived to the present. Even though colonialism precedes coloniality, coloniality survives colonialism.[6] Coloniality as Walter Mignolo elucidates, is the darker side of modernity.[7]

The Conquest of America. Violence and Resistance in the Permanent Collection of the Museo Reina Sofía

The violent conquest of America and the resistance to the system of domination are the historical vehicles we discover in the selection of works in the permanent collection of the Museo Reina Sofía assembled on the ground floor of the Sabatini Building under the title Apparatus '92. Can History Be Rewound?. The story they tell challenges the Spanish historical narrative and is led instead by the logic of decolonisation. They question Eurocentrism, the links between Western modernity and the structural violence defined by the rationales of colonial dispossession and subjectivity, as Françoise Vergès would say, by conflicts of gender and race, the exploitation of resources and people, the confiscation of lands, extractivism and the theft of history. In order for things to change, it is important to portray the workings of domination and coloniality in terms of dispossession, but it is also important that we bear in mind the place from which we are making these statements, that is, a national museum in Madrid, Spain, southern Europe; and the scope of our dialogue, which spans southern actors, from southern Europe and from the global South — in this case with the Atlantic as a geopolitical centre. Instead of simply celebrating modernity, couldn't we seek alternatives outside modernity itself?

Eurocentrism, i.e. the cognitive perspective of Europeans and of those educated under its aegis, considers Europe a universal model and has been used as a standard of power in the modern Western colonial world. Indeed, it originated the myth of modernity – regarded as a product of Europe – and provoked the emergence of the theory of the coloniality of power which, although devised in the South by intellectuals from the global South and rooted in the academic sphere, has proved essential for the development of new critical perspectives, and for the struggles of indigenous social movements. To paraphrase Aníbal Quijano, its first theoretician, the coloniality of power began with the conquest of America and pervades every aspect of life, its material and subjective dimensions.[8]

Coloniality constructs racist, classist, patriarchal and imperial reasoning based on Christianity and heteronormativity; it is hidden today in systems of domination such as institutional racism, patriarchal violence, and indigenous knowledge dispossession that transforms those peoples into foreigners to themselves. One of the strongest beliefs of the twentieth century was the notion that removing colonial administrations implied decolonising the world, hence the myth of a 'postcolonial' world.[9] Yet coloniality still inhabits fields of subjectivity, knowledge, sexuality and nature. Instability, wars, dictatorships, territorial struggles, neocolonialism, exploitation of natural resources and ethnic struggles derived from colonial apportionment are some of the consequences of decolonial processes, contemporary forms of violence that date back centuries. A striking example is Africa, whose present cannot be understood without remembering the slavery and European occupation sanctioned by the Conference of Berlin (1884–1885) and without discerning the economy of violence rooted in the original European nation-state project that replaced non-state forms of community organisation, in other words: the history of the world as a perpetual relationship of power between sovereigns and subordinates, a permanent conquest,[10] to use the term coined by Rita Segato for this rationale of conquest – or of capital – that is still valid today.

Violence, in its various applications, was a key part of the conquest of America and of the colonial rationale that explains many of the contradictions of Western modernity. Where do racist discourses, the reification of lives, the growing separation between nature and culture, structural violence and state violence come from?[11] The influence of European thought on the conquest and colonisation of America spread thanks to models of political and social control. The nation-state, for instance, involved the political emancipation of the former colonies and inventions of their histories, as Eric Hobsbawm would say, which imposed control on different aspects of everyday life.

Control processes continued to be reproduced following the independence of the colonies because those who handled them imposed the new models without bearing in mind the ideals and cultural worldviews of the earlier indigenous peoples. Local traditions were cast aside and natives were subordinated and subjected to unfair systems of racial division. Founded on violence, even on a continuum of violence – of a “(re)covert violence”, to rescue a term from Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui –[12], which perpetuates to the present, the new states – pure fictions of democracies in many cases – turned out to be failed, implacable solutions that reveal a historical continuity between the times of conquest, the colonial ordering of the subsequent world and the new world order derived from the decolonization wars of the 19th and 20th centuries. The colonial legacy can be found in cases such as that of the Guatemalan and Peruvian internal armed conflicts (1960–1996 and 1978–2000, respectively). Most of the victims of these conflicts were from the Ixil and Quechua peasant population, i.e., poor, historically excluded and persecuted, 'the condemned of the Earth', to quote Frantz Fanon, and their depersonalisation and reification, which can be traced back to the age of the Spanish conquest of America, places them closer to nature than to mankind.

Coloniality is a way of explaining structural violence in connection with the colonial past. Dehumanisation and reification enable us to establish connections between structural and colonial violence, yet another key factor was access to land and its distribution.Territory which had been divided into economiendas and latifundias, after independence processes fell into the hands of the most powerful families. I am referring to a new elite, in many cases of Spanish descent, that impoverished peasants and produced displacements and wars. It would also lead to great cultural and symbolic losses as a result of the break in the intergenerational transfer of knowledge that also implied a break in the animistic and sacred relationship with the land characterising premodern world views. Natives' age-old defence of the land is translated today in their resistance against the predatory strategies of neoliberalism. This continuity can be observed in different types of aggression against the most vulnerable: the assassinations of indigenous people in Guatemala, Peru, El Salvador and Chiapas, the disappearance of the students of Ayotzinapa in Mexico, the feminicide of activists Berta Cáceres in Honduras and Marielle Franco in Brazil, and the phenomenon of the drug cartels in countries such as Colombia in the nineties. This is the context of The Uncounted: A Triptych by Mapa Teatro, a work that metaphorically addresses the three faces of political violence in Colombia – the paramilitary, drug trafficking and guerrilla warfare – through visual references to festivities and parties.

Violence and impunity may explain this continuity in the colonial history of the world and in specific episodes, such as the struggle of Guatemalan indigenous communities against injustice leading to the neocolonial extractivist depredation of the present.[13] A theft of the land and also an epistemicide, a theft of language and history that activists like Aura Cumes, Mayan anthropologist from Guatemala, place at the heart of colonial history. The dispute of narratives, the writing of history as a truly common good, are part of the same struggle.

The Return of the Future

According to Filipino film maker Kidlat Tahimik, indigenousness isn't a cultural condition rooted in the past but a set of knowledges that show us a path to follow, a utopia that draws a horizon: 'I cannot erase history, but at least I can recognise it and try to build on the strengths of our parents to balance the strength of colonial values'.[14] Perhaps indigenous rationales contain alternatives to the logic of domination imposed by the conquest of America five centuries ago. For, alongside the history of repression there is a history of resistance, led by communities that for five hundred years have been sustaining alternative forms of organisation and dialectics to the reasonings behind of the conquest of America and Western modernity; communities that have preserved their knowledge, their cares and non-extractivist forms of co-existence so they may appear even marginally. This is what Aníbal Quijano terms the return of the future, that which was lost and is now regained; Rita Segato calls it the village-world, that which didn't disappear but remained discreetly hidden in order to survive, awaiting its moment to emerge. In her turn, Silvia Federici describes this recovery of traditional forms as a way of 're-enchanting the world',[15] recovering the sacredness that disappeared with extractivist and rational modernity. Restoring that which was displaced by modernity.

Indigenous resistance intensified in America with the social and political doctrine known as Zapatismo, the guerrilla movement founded by Emiliano Zapata that became a kind of theoretical inspiration for the alter-mondialist movement born in Seattle in 1999 during the protests against the World Trade Organisation. While alter-mondialism emerges as a feature of the global North, Zapatismo appears in the global South as a protest in relation to the indigenous liberation movements (Ecuador, Bolivia, Guatemala, etc.) that emerged in Latin America almost simultaneously. The EZLN enjoyed widespread support when it occupied several villages in the Mexican state of Chiapas on 1 January 1994 and read the First Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle, a text that aspired to bring visibility to native peoples and had very clear intentions. The struggle shouldn't only be about defending indigenous and territorial rights and identity – during the 1994 uprising, the EZLN seized and collectivised large extensions of land – and values like democracy, freedom and justice, but also about confronting the policies of neoliberalism. As a result of the convergence of their denunciations with those of the anti-globalisation movements that would surface shortly afterwards, Zapatismo generated a new type of networked solidarity structure, an emerging alter-mondialism – the confidence, before paralysing presentism, that another world is possible – that from a range of fields on a transnational scale tried to counter the neoliberal policies of globalisation. Zapatismo created a horizon of expectations, a space of resistance that has lasted to the present. In order to avoid another failure, perhaps what we need is to decolonise and de-neoliberalise our subconscious. Or, as Suely Rolnik would say, break the spell and deconstruct the colonial unconscious.

Agar Ledo Arias is an art historian and research curator at the Museum of Pontevedra. Between 2019 and 2022 she worked as a curator and acquisitions advisor in the Collections Department of the Museo Reina Sofía, where she was part of the curatorial team of "Communicating Vessels. Collection 1881-2021", the reformulation of the collection inaugurated in November 2021. Previously she has been responsible for the Exhibition Department at MARCO, Museum of Contemporary Art of Vigo (2006-2018), where she directed and coordinated the exhibition projects and site-specific productions for more than a decade (Tino Sehgal, Thomas Hirschhorn, Martin Creed, Tania Bruguera, Teresa Margolles...). Interested in the social and political implications surrounding artistic practice, Agar Ledo obtained a Master's degree in Museology and Museums (University of Alcalá) and a Master's degree in Art and Politics (MA Art & Politics, Politics and International Relations, Goldsmiths, University of London), training that she completed with scholarships and residencies at the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art (Norman, OK), Le Consortium (Dijon), Musée d'art contemporain de Lyon and ICI-Independent Curators International (New York). Her professional trajectory includes spaces such as the I International Biennial of Contemporary Art of Seville (2004), the Galician Center for Contemporary Art (CGAC, Santiago de Compostela, 1998-2004) or the Luis Seoane Foundation (A Coruña, 2005), where she is a member of the Board.

*Apparatus '92. Can History Be Rewound? exhibition at Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía was curated by Manuel Borja-Villel, Rosario Peiró, Agar Ledo Arias and Lluís Alexandre Casanovas Blanco.

This text was originally published in Spanish in the May 2024 issue of Le Monde Diplomatique, pp. 28-29 © Le Monde diplomatique en español

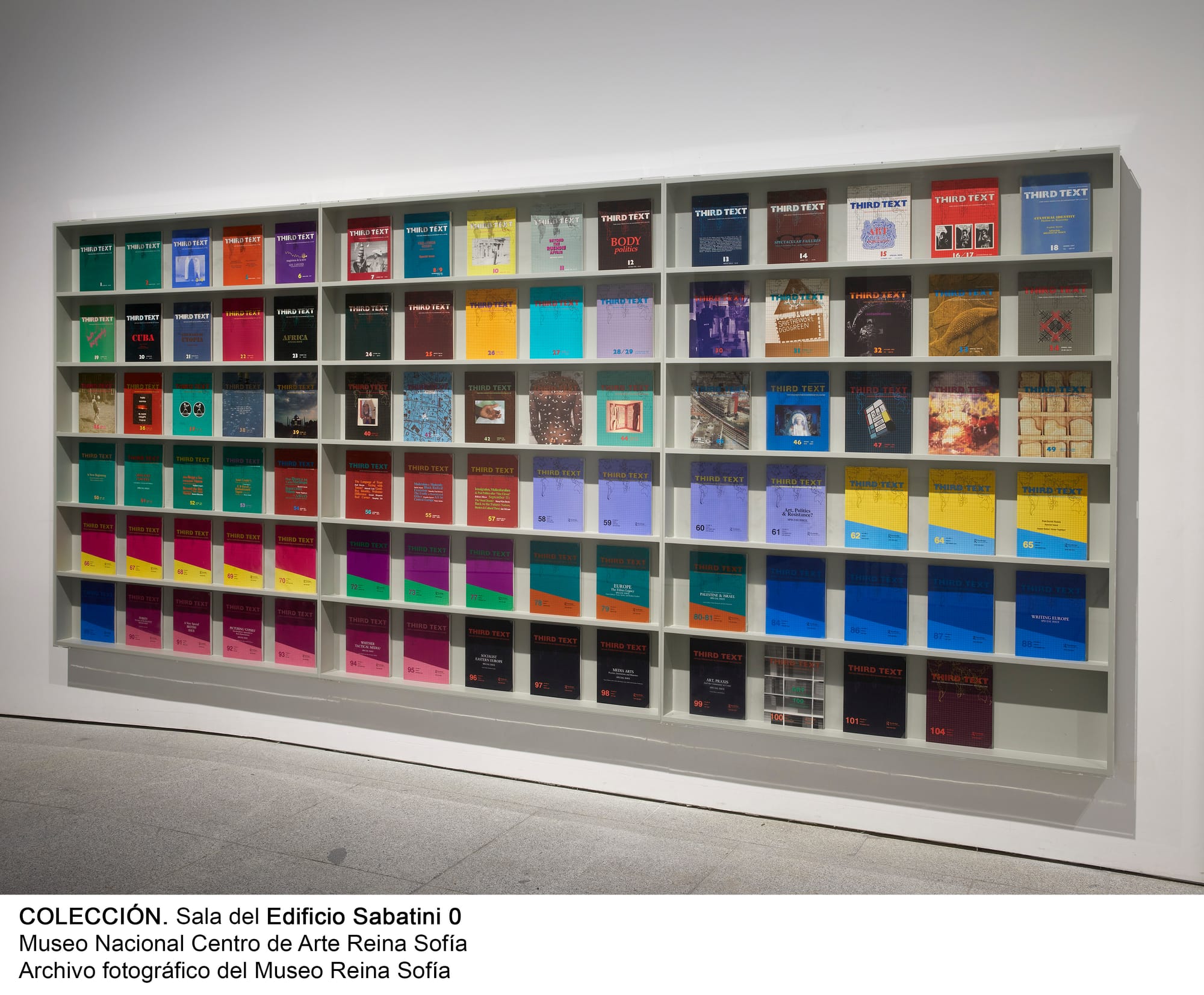

PHOTO 1

Rasheed ARAEEN. Pakistán, 1935

A Shelf for Third Text, 2021. Founded by the artist Rasheed Araeen in 1987, Third Text magazine (1987-2011) claims an emancipated and anti-colonial perspective against the Western hegemonic order that makes peripheral voices from Asian, African or Latin American contexts invisible. It is a clear exponent of Araeen's materialist practice, anchored to the struggles of his time. Influenced by authors such as Frantz Fanon and by the anti-racist movements that emerged in the United Kingdom with immigration from the last newly independent colonies, the activist dimension of his work was manifested, at that time, in curatorial projects such as The Other Story (Hayward Gallery, London, 1989).

Collection – Apparatus '92. Can History Be Rewound? View of the exhibition room at Edificio Sabatini 0, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, november de 2021

© Archivo fotográfico del Museo Reina Sofía

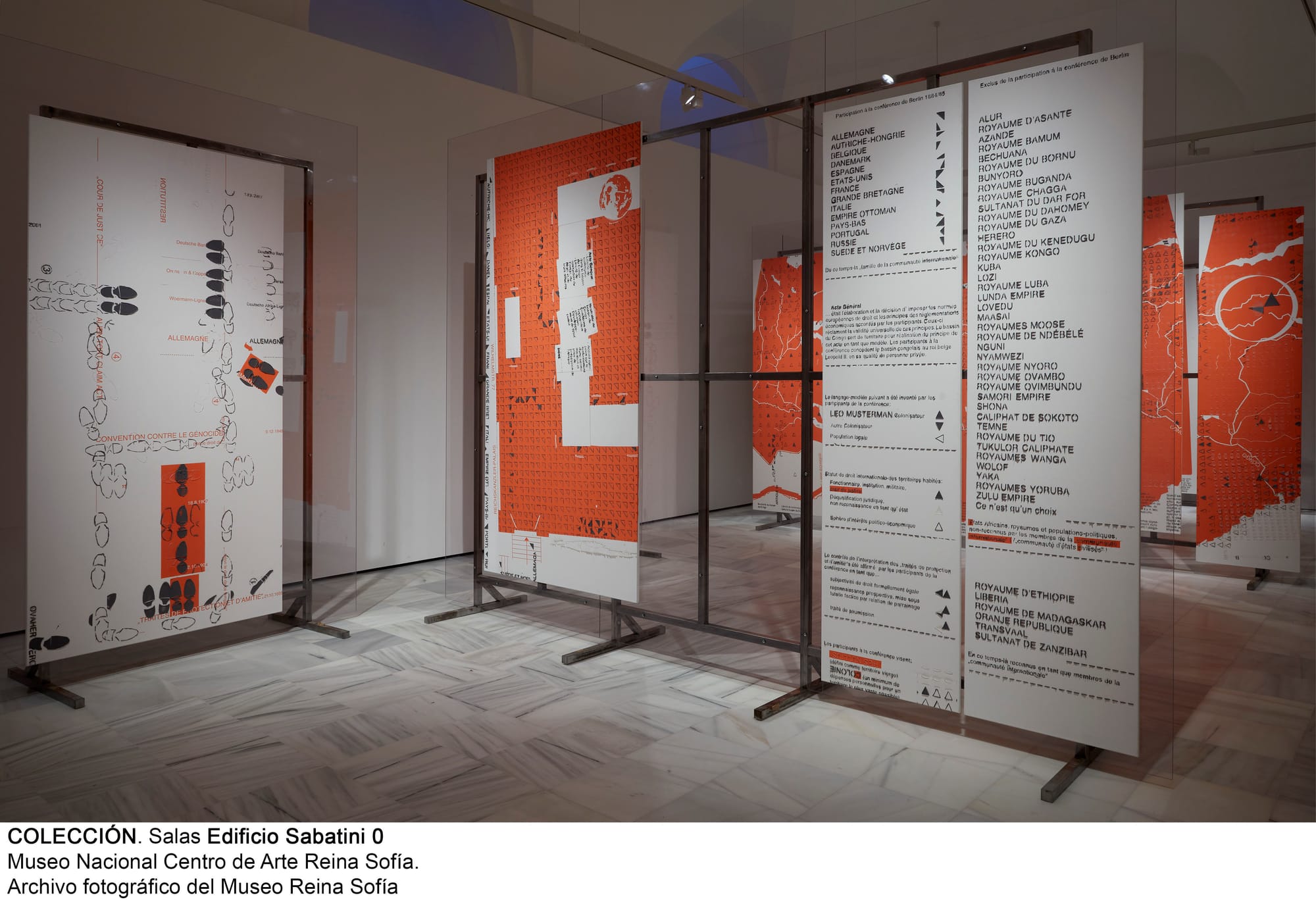

PHOTO 2

These works in the picture were part of the Plus Ultra project, conceived by curator Mar Villaespesa and the cultural production company BNV for the Andalusia Pavilion at Expo ’92. Plus Ultra questioned the Expo event both inside and beyond its site by its appropriation of the imperialist slogan “Plus Ultra / further beyond”.

1)Lenin Cumbe / Agustín Parejo School. Málaga, Spain, 1982 – 1994

Agustín Parejo School presenta a Lenin Cumbe, 1992. 12 painted and photographed televisions, with scenes and texts alluding to Latin American and Spanish affairs at that time.

2)Juan Delcampo (Pedro G. Romero, Abraham Lacalle, Chema Cobo y Luis Navarro), 1989

Mural that occupies, reproduces and manipulates the façade of the Museum of Contemporary Art of Seville with portraits of Charles V, Napoleon, the Catholic Monarchs, Columbus, Hernán Cortés. Scale reproduction from a front view photograph in the BNV file.

Collection – Apparatus '92. Can History Be Rewound? View of the exhibition room at Edificio Sabatini 0, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, november de 2021

© Archivo fotográfico del Museo Reina Sofía

PHOTO 3

Liliana Maresca. Argentina, 1951-1994

Ecuación - El Dorado (Equation – El Dorado), 1991. The piece is based on the myth relating gold and diamond-bearing areas of the old West Indies to this lost city, where unimaginable wealth was supposedly accumulated.

Collection – Apparatus '92. Can History Be Rewound? View of the exhibition room at Edificio Sabatini 0, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, november de 2021

© Archivo fotográfico del Museo Reina Sofía

PHOTO 4

Dierk Schmidt. Germany, 1965

Die Teilung der Erde (The Division of the Earth), 2004-2007. In the installation Die Teilung der Erde, Schmidt alludes to a key episode in history in terms of narrating colonialism: the Berlin Africa Conference of 1884–1885, during which European and US powers prepared the division of the entire continent.

Collection – Apparatus '92. Can History Be Rewound? View of the exhibition room at Edificio Sabatini 0, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, november de 2021

© Archivo fotográfico del Museo Reina Sofía

PHOTO 5

Mapa Teatro- Laboratorio de artistas (Heidi Abderhalden Cortés [Bogotá, Colombia, 1962]; Rolf Abderhalden Cortés [Manizales, Colombia, 1965])

The Unaccounted, 2014/2021. (The Unaccounted: A Triptych [Variation]) is part of the project Anatomía de la violencia en Colombia (Anatomy of Violence in Colombia).

Collection – Apparatus '92. Can History Be Rewound? View of the exhibition room at Edificio Sabatini 0, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, november de 2021

© Archivo fotográfico del Museo Reina Sofía

PHOTO 6

Carved and painted by members of the Zapatista communities, these cayucos traveled on the ship La Montaña across the Atlantic in 2021. In the background, installation by the Russian collective Chto Delat? that links the Zapatista news with the anniversary of the hundred years of the beginning of the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Collection – Apparatus '92. Can History Be Rewound? View of the exhibition room at Edificio Sabatini 0, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, november de 2021

© Archivo fotográfico del Museo Reina Sofía

[1]The housing bubble (which we could circumscribe to the years 1986 to 2008) had a long, complex and contradictory history full of ups and downs before the great crash in 2008.

[2]'Welcome to 1992, a year full of extraordinary events' was one of the messages that Channel 1 of the Spanish public television network (RTVE) broadcast on New Year's Eve of 1991.

[3]Founded by artist Rasheed Araeen in 1987, Third Text defended an emancipated anti-colonial gaze influenced by authors like Frantz Fanon and the anti-racist movements that emerged in the United Kingdom when the country welcomed immigrants from the last colonies that gained independence. Subirats's text was published in The Wake of Utopia, volume 6, issue number 21, 1992, pp. 57-66.

[4]Enrique Dussel, 1492 El encubrimineto del Otro. Hacia el orígen del 'Mito de la modernidad', Plural Editores/UMSA, La Paz, 2004.

[5] A politicisation caused by the economic and financial crisis of 1992-1993 derived, in turn, from the Gulf War of 1990-1991 and its impact on the price of oil. See Jorge Luis Marzo and Patricia Mayayo, Arte en España 1939-2015, ideas, prácticas, políticas, Cátedra, Madrid, 2015, pp. 663-666.

[6] See Nelson Maldonado-Torres, 'Sobre la colonialidad del ser: contribuciones al desarrollo de un concepto' in Santiago Castro-Gómez and Ramón Grosfoguel (eds.), El giro decolonial: Reflexiones para una diversidad epistémica más allá del capitalismo global, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana/Siglo del Hombre Editores, Bogotá, 2007. p. 131.

[7] Walter D. Mignolo, Desobediencia epistémica: Retórica de la modernidad, lógica de la colonialidad y gramática de la descolonialidad. Argentina, Ediciones del Signo, Buenos Aires, 2010. pp. 9-10.

[8] Aníbal Quijano, 'Colonialidad del poder y clasificación social', in Santiago Castro-Gómez and Ramón Grosfoguel (eds.), El giro decolonial: Reflexiones para una diversidad epistémica más allá del capitalismo global, op. cit.

[9] See Ramón Grosfoguel, 'Implicaciones de las alteridades epistémicas en la redefinición del capitalismo global: transmodernidad, pensamiento fronterizo y colonialidad global' in Mónica Zuleta Pardo et al., ¿Uno solo o varios mundos? Diferencia, subjetividad y conocimientos en las ciencias sociales contemporáneas, Siglo del Hombre Editores, Bogotá, 2007, pp. 99-116. Available at http://books.openedition.org/sdh/416. See, too, https: //www.decolonialthoughts.com/post/is-colonisation-still-relevant-when-discussing-african-issues

[10]See Rita Segato, https://read.dukeupress.edu/critical-times/article/1/1/212/139311/Manifiesto-en-cuatro-temas and http://asociacionlatinoamericanadeantropologia.net/revista-plural/wp-content/uploads/numero03/articulo-4.pdf

[11]See Pilar Calveiro, Resistir al neoliberalismo: comunidades y autonomías, Siglo XXI, Mexico City, 2019.

[12]See Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Violencias (re)encubiertas en Bolivia, Primera edición en Panamá/España (Santander: Otramérica, 2012).

[13] Described in the audio-visual works by film maker and human rights activist Pamela Yates (USA, 1962).

[14] https://www.acuartaparede.com/kidlat-tahimik-mestre-de-cinema/

[15] See https://enriquedussel.com/txt/Textos_200_Obra/PyF_revolucionarios_marxistas/Sueno_zapatista-Yvon_Le-Bot.pdf and https://www.traficantes.net/sites/default/files/pdfs/map60_Reencantar_interior_web.pdf